A resounding peace

by Pedro ZarralukiIrene and I reached a point where we overdosed on silence, although not long before it had seemed normal to us to be surrounded by sound. Not a single thought about the importance of sound or of its absence had ever crossed our minds. Our research into silence had its origins in an upheaval in our lives. Up until then Irene had worked as a freelance, making regular contributions to a publisher specializing in encyclopedias. She had just finished a series of installments, which, under the somewhat Hitlerian title My One and Only Friend, aimed at acquainting readers with the different breeds of dog. At that moment Irene was an authority on canines, just as, the year before, she had been a leading expert on experiments for young students. From the refraction index to Yorkshire terriers, each new project would make her forget all she knew about the previous one. Irene would boast that the way she amassed knowledge was very similar to the sex life of those who claim to be serial monogamists. What Irene could not have known was that the last canine entry would also mark the end of her association with the publisher. They called to tell her there was nothing new in the pipeline (which was untrue, because she knew they were compiling an encyclopedia on transportation as well as a series on lost civilizations), and advised her to look for another publisher, as they were about to carry out an imminent restructuring. In the world of freelance contributors, the term imminent restructuring means the publisher has decided to do without you. And so Irene was out of work, and that was just the start of our misfortunes. I had been writing a novel for the past three years, and to be brutally honest, the result was decidedly inferior to what I had when I began. At first impatient, and then worried, my publisher ended up looking at me with unremitting pity each time I announced (in an increasingly excited voice and an ever gloomier expression) the forthcoming conclusion of my book. What with one thing and another we were on the verge of financial collapse, if indeed the word collapse can be applied to something that has never had any substance, but has simply flowed like a river, or like life, or other elusive things. And so one morning, Irene and I found ourselves eating breakfast on our tiny terrace under the shade of the bamboo plants, and we realized we could go on eating breakfast forever because we had nothing better to do. After two hours engaging in that necessarily finite activity (how absurd to be still having breakfast as night fell), we decided to burn our boats and seize the opportunity to go on a trip. We rejected our initial ideas, splendid though they were, because of the cost. Then we considered more affordable destinations with less exotic names. I even pointed out, forgetting the person I was talking to, that neither the authors of great literature nor good travelers have ever needed costly settings. Irene remained serenely silent. She had always chosen The Alexandria Quartet over Diary of a Country Priest, with a vehemence that rejected the possibility that both novels might be excellent. For Irene, literature was a call from the far side of the mountain, and the main characters of all great novels had to be people who wandered off to remote places. As I was buttering my sixteenth slice of Melba toast, it struck me that Rioja was a place we had already enjoyed countless times through its wines. Our bodies had absorbed copious amounts of phosphorus, calcium and potassium from Rioja’s soil. You could say we had drunk it down a thousand times without ever setting foot in the place. I suggested a trip there and Irene accepted enthusiastically.

“It’ll be like a journey to the source of life,” she said, a dreamy look in her eyes.

Two days later we were driving in a rented convertible across the Monegros Desert. It was June and already very hot. The sun was so fierce we didn’t dare open the sunroof. Irene hummed as she saw the mileposts go by, and we felt quite happy. We drove down a long stretch of highway that seemed like the road to infinity. My hand nestled in Irene’s lap. The purr of the engine lulled us. Suddenly, as if to wake us up, there was a ghastly screeching sound. Instinctively, I lifted my foot off the gas pedal, and when I pressed it down again we heard a noise like someone rattling a can full of nuts and bolts. The wheels hadn’t locked, but nothing would get the car moving again. I pulled over to the side of the road. We opened the hood, because throughout history that is what people have always done when a car breaks down, regardless of whether they have any mechanical skills. We peered at the engine, from opposite sides of the vehicle. The contemplation of a car engine, which is invariably a heap of greasy, old machinery, offers few clues to the uninitiated. All I could do was sigh, at a loss as to how it had kept going until a few short moments ago.

“Maybe it’s this tube here,” said Irene, who was stubborn and headstrong, pointing randomly at a cylinder that looked frankly alarming.

The silence was so intense that her muffled voice seemed to emerge from everywhere at once. There were no trees around us, only a desolate landscape of fissured rocks. Then, very gradually, we became aware of a faint noise coming from somewhere.”

One glance was enough to reveal several other parts that looked even more distressing. I climbed back into the car and turned the key in the ignition. But as soon as I pressed down on the accelerator the same rattle of nuts and bolts started up. I got out slowly, stretched my arms, and announced it was the transmission. I did so with the assurance of doctors when they diagnose a viral infection and tell you to give it time. And so we sat down on a rock and we waited. The air was still, the road deserted. Irene started humming again. The silence was so intense that her muffled voice seemed to emerge from everywhere at once. There were no trees around us, only a desolate landscape of fissured rocks. Then, very gradually, we became aware of a faint noise coming from somewhere. More precisely, we were suddenly aware that a distant noise had grown steadily louder until it became audible. We waited, and the sound grew louder. We could make out the shape of a car approaching on the road, but we did not move. It sped past us unleashing a tornado of sound, a sudden explosion that died away as slowly as it had announced its arrival. Moments later we found ourselves once again immersed in the same absolute calm. I closed my eyes, my head spinning slightly, and felt as if I was disengaging from the Earth. I found myself floating in the darkness of outer space, wallowing in infinite peace, in a relentless emptiness, where time and waiting didn’t exist. My mind was a complete blank, and all I could feel was my own weightlessness. While I was daydreaming, a faint sound made me look to one side. And so I became an absent witness to the movement of our planet leaving in its wake a shimmering tail of light. The image passed me by just as the car had done, surrounded by a sudden tornado of banging, of noise and laughter. Then it spun away from me. As it disappeared into the darkness, peace returned, and at some point (impossible to say exactly when) I stopped hearing it completely and was enfolded by absolute calm.

I opened my eyes and looked at Irene. She too had closed her eyes. Her head was tilted back and her lips were quivering.

“We could write a book about silence,” I said.

Her mouth curved into a smile, which broadened as her thoughts began to race. Irene’s most dazzling smiles were the ones that came from deep inside. She remained motionless for a few more moments. Then she leapt to her feet and looked at me, brimming with enthusiasm.

“It will require an enormous amount of work,” she said, tainted perhaps by an understandably (in her case) encyclopedic attitude. “Why did cinemas hire piano players during the silent movie era? Is silence bearable? Is there such a thing as silence or is it just an accumulation of distant sounds? Which do we find more nerve-racking: noise or the absence of noise? On the other hand, haven’t we all at some point or another been forced to remain silent? Who did so out of self-interest, out of weakness or perversion? Who has saved and who condemned others by his or her silence? Can one spend a whole lifetime waiting for a question to be answered? Does absolute silence, the silence of God, really exist, or is it simply a metaphor for ignorance? Can silence be bottomless, as deep as a well? Can one feel comfortable inside a well? Why isn’t absolute silence described as something boundless, like the calm, empty spaces of the universe? Can silence be methodical without seeming artificial? Have you ever been to a wake? Isn’t it true that the only ones who behave naturally at a wake are the dear departed because they are so damned silent? On the other hand, is hearing nothing from a loved one for twenty years the most unbearable type of silence? Why do we wait patiently but not eternally for a simple word that would put an end to our pain? Why do we say that someone broke the silence instead of freeing the silence or calming it, which would be very poetic and would prevent that ringing in our ears we find so annoying? Why do we say someone is the silent type, as if they went through life on tiptoes, when in fact that person simply doesn’t talk much? Is talking the most deliberate way to break the silence? Why does silence seem awkward at dinner parties and not on mountaintops? What happens at those rare dinner parties that are held on a mountaintop? How can keeping silent be the noblest and the most despicable act when what is being kept is exactly the same thing? Why don’t you say something? You’re letting me do all the talking. Is silence a betrayal of evolution, perhaps, and thus a fleeting omen that everything comes to an end?”

When Irene finally stopped talking, her agitated words lingered in the still air. I contemplated the barren landscape, thinking how difficult it was going to be to give shape to all this. But my mind was teeming with ideas. Irene and I looked straight at each other, both of us immersed in thought, that rigorously silent, overwhelming activity. I had the strange impression that everything around us had come to a halt, like the ominous calm that precedes the deadliest storms.

From The History of Silence, translated by Nick Caistor and Lorenza García.

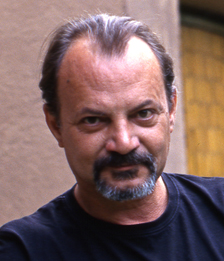

Pedro Zarraluki’s La historia del silencio (1994) won the Herralde Award and is now published in English for the first time. His other novels include El responsable de las ranas (‘In Charge of Frogs’, 1990), winner of the Ciudad de Barcelona and RNE Ojo Crítico awards and Un encargo difícil (‘A Difficult Assignment’), the 2005 Nadal Award-winner and shortlisted for the Fundación José Manuel Lara Award. His latest story collection is Te espero dentro (‘I Wait For You Inside’, 2013). He is a regular contributor to the press and radio, and teaches creative writing at the Ateneo Barcelonés. The History of Silence is published internationally by Hispabooks. Read more.

Pedro Zarraluki’s La historia del silencio (1994) won the Herralde Award and is now published in English for the first time. His other novels include El responsable de las ranas (‘In Charge of Frogs’, 1990), winner of the Ciudad de Barcelona and RNE Ojo Crítico awards and Un encargo difícil (‘A Difficult Assignment’), the 2005 Nadal Award-winner and shortlisted for the Fundación José Manuel Lara Award. His latest story collection is Te espero dentro (‘I Wait For You Inside’, 2013). He is a regular contributor to the press and radio, and teaches creative writing at the Ateneo Barcelonés. The History of Silence is published internationally by Hispabooks. Read more.

Author portrait © Gabriela Grech

Nick Caistor is a translator of fiction from Spanish, French, and Portuguese, including works by Eduardo Mendoza, Juan Marsé, Manuel Vazquez Montalbán and José Saramago. Lorenza García graduated from Goldsmith’s College, London, with First Class Honours in Spanish and Latin American Studies and since 2007 has translated eighteen novels and works of non-fiction from the French and Spanish, most recently in collaboration with Nick Caistor. Their co-translation of Andrés Neuman’s Traveller of the Century (2012) was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, the Valle-Inclán Spanish Translation Prize and the Dublin IMPAC Award.