F. Scott Fitzgerald bathes in the light on the French Riviera

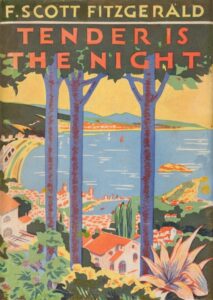

by Travis ElboroughF. Scott Fitzgerald’s (1896–1940) literary brilliance as the witty and worldly-wise chronicler of the Jazz Age and his youthful, suntanned good looks were regularly commented on during his heyday in the 1920s. Later, in the light of what followed, they were recalled in sorrow, anger and disappointment. By the time the writer died in Hollywood in 1940, this once-golden boy was a severely tarnished alcoholic, all but forgotten by the reading public; Tender is the Night, the novel he’d slaved over for nearly ten years, was a critical and commercial failure and out of print, and original unsold copies of The Great Gatsby were still going begging.

Still, in the epoch when Fitzgerald first blazed on to the literary scene, a suntan remained a daringly modern thing: a badge of leisured cosmopolitan sophistication for those who could afford it. Its newfound vogue in the aftermath of the First World War – and its subsequent promotion, with the aid of Coco Chanel in the pages of Vogue – owed a good deal to the near simultaneous adoption of the French Riviera as summer destination by a set of sun-worshipping artistic Americans, including Fitzgerald, his wife Zelda, and Gerald and Sara Murphy.

Fitzgerald dedicated Tender is the Night to the Murphys (the book’s tribute runs, ‘To Gerald and Sara – Many Fêtes’), and the couple were the inspiration for Dick and Nicole Diver, the novel’s glamorous protagonists. Though Dick, a psychiatrist who loses it to drink over the course of the novel, notoriously morphs into a version of the author himself, while the beautiful, neurotic Nicole was based far more closely on Fitzgerald’s mentally unstable wife than the real-life Sara.

Sara was the eldest daughter of a millionaire Cincinnati ink manufacturer, and partially raised in Europe, where she mingled in German and British aristocratic circles. Gerald was the Yale-educated second son of a well-read owner of a prosperous New York luxury goods store. Subjected to family opprobrium about their marriage (Sara’s father was particularly unhappy about her choice of husband) and repelled by the stuffiness of materialist, elite American society, the Murphys had moved to Paris in 1921. Another motivating factor in their transatlantic migration was that exchange rates were immensely in their favour. The imbalance between the US dollar and the French franc allowed them to live well on a smaller share of Sarah’s trust fund, thereby avoiding further awkward questions about Gerald’s career prospects and his semi-abandoned study of landscape architecture at Harvard into the bargain. A similar financial calculation was also to bring the more cash-strapped Fitzgeralds to France. Something that the writer would describe in ‘How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year’ – a humorous piece for the Saturday Evening Post in 1924 on the advantages of slumming it on the Continent.

In the early summer of 1922 – a literary annus mirabilis in which James Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land were published, and the temporal setting for The Great Gatsby – the Murphys headed to Houlgate, a seaside resort in Normandy that was then popular with fashionable Parisians. While there, though, they were invited to join thecomposer Cole Porter (a friend of Gerald’s from Yale) and his wife, Linda, in a villa they’d rented in Antibes in the south of France. Gerald would later credit Porter with always having ‘a great flair, a sense of the avant garde, about places’ and when speaking to the New Yorker magazine in 1962, reiterated that at that time ‘no one ever went near the Riviera in summer’. Porter never returned to Antibes. But the Murphys were smitten.

With our being back in a nice villa on my beloved Riviera, I’m happier than I’ve been for years. It’s one of those strange, precious and all too transitory moments when everything in one’s life seems to be going well.”

The following year they persuaded the manager of the Hôtel du Cap at Antibes to keep his establishment (which usually closed on 1 May) open with a skeleton staff for the summer and a return visit. A precedent was established. And the pioneering Murphys, having encouraged friends and other like-minded, free-spirited types to join them, now worried about losing their unspoiled idyll to incomers. They responded by purchasing a house at 112, chemin des Mougins on the slope of Golfe-Juan in Antibes, where they would entertain in high, if informal style. They christened the property Villa America, and had it remodelled on modern art deco lines with a Moroccan-style flat roof, expressly for sunbathing.

These renovations were, however, still ongoing when the Murphys returned to Antibes for the summer of 1924 and so they booked themselves once more in to the Hôtel du Cap. It was here that the Fitzgeralds visited them that August, the couples having met in Paris that spring. Fitzgerald was to open Tender is the Night with a description of the Hôtel du Cap, which he fictionalized as Gausse’s Hôtel des Étrangers, and perhaps even more fruitlessly (since its true identity was obvious to everyone), sought to disguise it ever so slightly by pinking-up its white walls:

‘On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera… about half way between Marseilles and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel. Deferential palms cool its flushed façade, and before it stretches a short dazzling beach… The hotel and its bright tan prayer rug of a beach were one.’

Like the youthful Rosemary Hoyt and her mother at the start of the novel, the Fitzgeralds had journeyed to the Riviera from Paris by train. Initially lodging in the sleepy coastal town of Hyeres, which Zelda considered dreary, they soon moved to Saint-Raphaël, which Fitzgerald characterized as ‘a little red town built close to the sea, with gay red-roofed houses and an air of repressed carnival about it.’ It was in a rented house here, Villa Marie, that Fitzgerald knuckled down to work on The Great Gatsby – the blinking green beam of the lighthouse off shore at Cap d’Antibes has been held as the probable inspiration for light on the dock that signals Jay Gatsby’s yearning for Daisy in the novel.

Zelda, meanwhile, left with little too do, embarked on a brief, if possibly unconsummated, love affair with Edouard Jozan, a dashingly handsome and darkly tanned young French aviator. On discovering his wife’s infidelity, Fitzgerald fell into a jealous rage and kept Zelda locked in her room until she promised never to see Jozan again. Their marriage, if already turbulent, would start to go from bad to worse; and Zelda’s mental health with it. She nevertheless was to remember Jozan in her semi-autographical novel Save Me the Waltz, giving the book’s heroine, Alabama Beggs, an extramarital romance in the French Riviera with a pilot named Jacques Chevre-Feuille.

The Fitzgeralds were to spend most of the next five summers in the Riviera, including two years running at Villa St Louis, a house on the sea wall in Juan-les-Pins, where the writer, having finally completed The Great Gatsby, appears to have been as his most content. ‘With our being back in a nice villa on my beloved Riviera (between Nice and Cannes)’, he reported in one letter, ‘I’m happier than I’ve been for years. It’s one of those strange, precious and all too transitory moments when everything in one’s life seems to be going well.’

Inevitably, it was not to last. The Wall Street Crash, the premature death of the Murphys’ beloved son Patrick in 1929, Fitzgerald’s uncontrolled drinking and Zelda’s increasing instability were all to call time on those glorious summers in the south of France. Fitzgerald’s attempts to convey them in book form, a process seriously hindered by his alcoholic intake, would win him few admirers when Tender is the Night was published in 1934. At the height of the Great Depression, the novel was savaged by critics as a decadent throwback and the book appalled the Murphys; Sara, especially, was hurt and angered by it. Yet it stands as a curious, if flawed, picture of a time and a place, an odd kind of testament to the Riviera’s importance to Fitzgerald, and the effect, both good and ill, it had on his life and writing.

from The Writer’s Journey: In the Footsteps of the Literary Greats (White Lion Publishing, £20)

Travis Elborough is an author and social commentator whose work delves into the ephemera of retro culture as well as the history of London, geography and a broad range of other subjects. His Atlas of Vanishing Places won the Illustrated Book of the Year at the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards in 2020, and he has also written The Bus We Loved, a passionate love letter to the Routemaster bus which defined London transport for more than 50 years. His other works include A Traveller’s Year, A London Year, The Long-Player Goodbye, Being a Writer and A Walk in the Park. A regular contributor to Radio 4 and the Guardian, he has written for the Times, Sunday Times, New Statesman, BBC History Magazine and Kinfolk among others, and is a visiting lecturer at the University of Westminster, where he teaches creative writing. The Writer’s Journey is published by White Lion Publishing in hardback and eBook.

Travis Elborough is an author and social commentator whose work delves into the ephemera of retro culture as well as the history of London, geography and a broad range of other subjects. His Atlas of Vanishing Places won the Illustrated Book of the Year at the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards in 2020, and he has also written The Bus We Loved, a passionate love letter to the Routemaster bus which defined London transport for more than 50 years. His other works include A Traveller’s Year, A London Year, The Long-Player Goodbye, Being a Writer and A Walk in the Park. A regular contributor to Radio 4 and the Guardian, he has written for the Times, Sunday Times, New Statesman, BBC History Magazine and Kinfolk among others, and is a visiting lecturer at the University of Westminster, where he teaches creative writing. The Writer’s Journey is published by White Lion Publishing in hardback and eBook.

Read more

traviselborough.co.uk

@QuartoKnows

Instagram: whitelionpublishing

quartobooksuk

Author portrait © Andrew Pinder