The seductive spark of danger

by Marcus AlexisI still remember the awe and unease I felt as a child at the arrival of the wrecking machines in Barbapapa’s New House, a brilliant but unnerving picture book by Annette Tison and Talus Taylor that channelled the urban alienation of its time. And, with his “terrible teeth and terrible claws”, Maurice Sendak has surely evoked similarly visceral reactions in generations of children to the twin threats of danger and abandonment explored in Where the Wild Things Are. In Tomi Ungerer’s The Three Robbers, it is the axe, the blunderbuss and the pepper spray introduced in the opening pages that form the dramatic opening of one of the best picture books ever written.

However, unlike these stories, or traditional fairy tales about wolves and axes, similarly candid explorations of danger in contemporary picture books seem vanishingly rare.

In the story of The Great Fire of London I saw opportunity to explore these themes. The fire is immediately captivating – which is perhaps why it is on the primary school curriculum. The scale of the destruction; our morbid fascination with this period of gallows and gunpowder; and its setting in the narrow streets of medieval London draw us in.

The fire was, of course, a tragedy of much greater proportions than the reported death toll suggests; but our emotional response is lessened by the passage of time. Our society prefers representations of violence to be set in the distant past. If I wanted to emulate the titles I loved and create stories with atmosphere and darkness, history was rich with potential.

As the focus of the book, Thomas lends a great historical event a human scale and puts a relatable ‘everyday’ character at the centre of events.”

The primitive firefighting methods of the time often amounted to little more than fire hooks and leather buckets. Wikimedia Commons

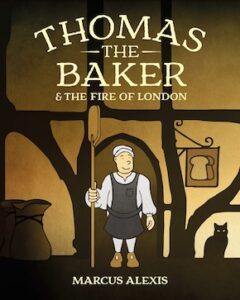

It is received wisdom that one prerequisite of a successful children’s title is having a child or animal as the central character; but I find something compelling about a hapless adult character. The Great Fire offers a surprisingly rich cast of true-life characters including King Charles II, Samuel Pepys, the infamous Mayor of London (Thomas Bloodworth) and Christopher Wren. I chose the unfortunate baker, Thomas Farriner; a character who wouldn’t warrant a footnote in history if it were not for his terrible luck that late summer’s night.

As the focus of the book, Thomas lends a great historical event a human scale and puts a relatable ‘everyday’ character at the centre of events. Empathy is felt most keenly for those with whom we can identify; and we all make mistakes. Moreover, there is something too perfect about an unfortunate baker residing in Pudding Lane (although the name is thought to refer to the offal that fell from passing butcher’s carts).

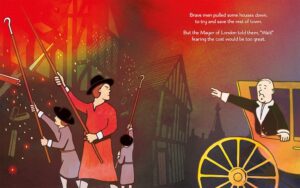

I tried to convey the mayor’s disinterest through his not leaving his carriage as brave townsfolk battled the blaze.

Click on images to enlarge and view in slideshow

To condense the story into fifteen spreads required a great economy. I am not a historian and while no one would expect ‘the whole truth’ from a rhyming storybook, to materially depart from the truth would undermine the integrity of the book. Describing the passage of time is a drag; hopefully I will be forgiven for condensing historical events that happened over several days into one – unspoken but unbroken – timeframe that you might describe as a ‘storybook day.’

Conveniently from the perspective of framing the story for children, Thomas really did work for the king. His bakery had a contract with the Royal Navy for the supply of ship’s biscuits. Even more surprisingly, he not only survived the Fire, but was able to rebuild his business unmolested in Pudding Lane. However, from a storytelling perspective, this absence of any reversal in his fortunes was rather unsatisfactory. My solution was to take my one conscious liberty with the truth and have Thomas initially bake bread for the king, with baking ship’s biscuits acting as the punishment at the end of the story. One of the key sources for the Great Fire are the diaries of Samuel Pepys, whose provisioning work for the Royal Navy involved meeting suppliers and handing out contracts; although I could not find room in the story for Mr Pepys, I like to think he and Thomas may have been known to one another.

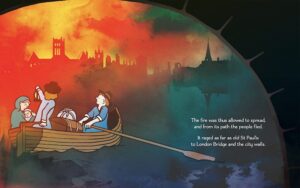

With the roads soon clogged, boats and ferrymen were every bit as valuable to the fleeing townsfolk as carts and horses. Alamy

Putting the story into verse only compounded the difficulty of being concise and truthful, resulting in a positively glacial daily word rate. The usual constraints (words that have no rhyme, pronouns can only follow character names, each adjective or synonym can only appear once in the text), magnified the difficulty of expressing concepts such as the mayor not having the authority to order houses be pulled down without the permission of the owners on pain of bearing the cost himself (yet some houses were pulled down). As a result, some spreads were rewritten fifty times.

Picture research threw up more questions. It is surprising how having to draw something tests your understanding of it when gleaned from surviving accounts. There were huge waterwheels under the arches of London Bridge that powered a pressurised water system connected to communal pumps. However, as each firefighting contingent desperately proceeded to dig up and break into the (wooden!) pipes, they rapidly ceased to function. The waterwheels themselves were soon destroyed by the fire, before a gap in the houses on the bridge checked the fire’s progress south. The primitive engineering and manufacture of the time mean the sources for portable water pumps look like the fantastical contraptions of Leonardo Da Vinci. Fire hooks are still a mystery to me, these were apparently used to “pull down buildings”, but can you imagine levelling a Tudor house with a hook? I suspect they were mostly used for pulling away thatch or retrieving smouldering timbers.

To illustrate the text on this spread I needed a view that encompassed both London Bridge and Old St Paul’s.

Once the fire was established, a combination of poorly enforced building regulations, an exceptionally dry summer and a persistent wind rapidly produced an unmanageable situation. It remains unclear whether quicker action by the mayor would have checked its progress. Whilst most activity centred around escaping the path of the fire (hampered no doubt by the townsfolk’s desire not to abandon their possessions), I do depict some of the many brave firefighters who did battle with the flames.

Despite his late arrival, King Charles II’s response is considered to be his finest hour. If the wind had not died down, the fire could never have been brought under control; but it also took the ‘kingly’ authority the mayor lacked to halt it. Charles was both decisive and tireless and by some accounts oblivious to all danger, perhaps even heroic.

The decision to fight fire with fire by blowing up houses with gunpowder fetched from the Tower of London gave me an explosive climax to the story (as well as an excuse to include halberds).

I frequently found the necessary economies and rewrites maddening, but ultimately hugely satisfying. I have already completed another history-based storybook, Colonel Blood & the Crown Jewels, which was a dramatic though near-bloodless affair (the thief escaped the gallows – but that is another story). However, I like to think the death of a character should not be out of bounds for a children’s book – which would suggest all sorts of possibilities for gunpowder, treason and plot!

Marcus Alexis is a designer, illustrator and writer. He was born and brought up in Cambridge. After studying at the art foundation course founded there by Ruskin, he moved to London to study Graphic Design, afterwards pursuing a career as a commercial designer at the BBC and various agencies before moving to illustration. He has since returned to Cambridge where he lives and works from home with his partner – a writer – and their two young boys. Thomas the Baker & The Fire of London is published by Cranthorpe Millner on 26 July.

Marcus Alexis is a designer, illustrator and writer. He was born and brought up in Cambridge. After studying at the art foundation course founded there by Ruskin, he moved to London to study Graphic Design, afterwards pursuing a career as a commercial designer at the BBC and various agencies before moving to illustration. He has since returned to Cambridge where he lives and works from home with his partner – a writer – and their two young boys. Thomas the Baker & The Fire of London is published by Cranthorpe Millner on 26 July.

marcusalexis.co.uk

Instagram: marcusalexispic

Twitter: @MarcusAlexisPic

@CranthorpeBooks