A seer is a liar

by Simon Critchley

“Delightful, highly readable… funny, moving and passionate.” Rick Moody, Salon

There is a view that some people call ‘narrative identity’. This is the idea that one’s life is a kind of story, with a beginning, a middle and an end. Usually there is some early, defining, traumatic experience and a crisis or crises in the middle (sex, drugs, any form of addiction will serve) from which one miraculously recovers. Such life stories usually culminate in redemption before ending with peace on earth and goodwill to all men. The unity of one’s life consists in the coherence of the story one can tell about oneself. People do this all the time. It’s the lie that stands behind the idea of the memoir. Such is the raison d’être of a big chunk of what remains of the publishing industry, which is fed by the ghastly gutter world of creative writing courses. Against this, and with Simone Weil, I believe in decreative writing that moves through spirals of ever-ascending negations before reaching… nothing.

I also think that identity is a very fragile affair. It is at best a sequence of episodic blips rather than some grand narrative unity. As David Hume established long ago, our inner life is made up of disconnected bundles of perceptions that lie around like so much dirty laundry in the rooms of our memory. This is perhaps the reason why Brion Gysin’s cut-up technique, where text is seemingly randomly spliced with scissors – and which Bowie famously borrowed from William Burroughs – gets so much closer to reality than any version of naturalism.

The episodes that give my life some structure are surprisingly often provided by David Bowie’s words and music. He ties my life together like no one else I know. Sure, there are other memories and other stories that one might tell, and in my case this is complicated by the amnesia that followed a serious industrial accident when I was eighteen years old. I forgot a lot after my hand got stuck in a machine. But Bowie has been my soundtrack. My constant, clandestine companion. In good times and bad. Mine and his.

The truth content of Bowie’s art is not compromised by its fakery. It is enabled by it.”

What’s striking is that I don’t think I am alone in this view. There is a world of people for whom Bowie was the being who permitted a powerful emotional connection and freed them to become some other kind of self, something freer, more queer, more honest, more open, more exciting. Looking back, Bowie was a kind of touchstone for that past, its glories and its glorious failures, but also for some kind of constancy in the present and for the possibility of a future, even the demand for a better future. Bowie was not some rock star or a series of flat media clichés about bisexuality and bars in Berlin. He was someone who made life a little less ordinary for an awfully long time.

…

Consider Bowie’s lyrics. It seems that – right from the beginning – we could not help but read them autobiographically, as clues and signs that would lead us to some authentic sense of the ‘real’ Bowie, his past, his traumas, his loves, his political views. We longed to see his songs as windows on to his life. But this is precisely what we have to give up if we want to try and misunderstand Bowie a little less. As we know all too well, he occupied a variety of identities. His brilliance was to become someone else for the length of a song, sometimes for a whole album or even a tour. Bowie was a ventriloquist.

This wasn’t a strategy that died with Ziggy onstage at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973. It persisted right through to Bowie’s final two albums, The Next Day and Blackstar.

On The Next Day many of the songs are written from an other’s identity, whether the menacing and dumb perpetrator of a mass shooting, as on ‘Valentine’s Day’, or the enigmatic persona on the final track, ‘Heat’. The latter has perhaps the strongest and most oblique lyric on the album, which concerns a son’s loathing for a father who either ran a prison or turned their home into a prison. There is an apparent allusion to Mishima’s Spring Snow and the following arresting image:

Then we saw Mishima’s dog

Trapped between the rocks

Blocking the waterfall.

Bowie sings repeatedly, “And I tell myself, I don’t know who I am.” The song ends with the line, “I am a seer, I am a liar.” To which we might add, Bowie is a seer because he is a liar. The truth content of Bowie’s art is not compromised by its fakery. It is enabled by it.

Otherwise said, Bowie evokes truth through ‘Oblique Strategies’, which was the name given to a series of more than a hundred cards that Brian Eno created with artist Peter Schmidt in 1975. For example, during the recording of ‘V-2 Schneider’ (the title is both a pun on the V-2 rocket that decimated parts of London in 1944 and the two core members of Kraftwerk – we two = Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider), Bowie accidentally began playing the sax on the offbeat. Just prior to the recording, he had read one of the ‘Oblique Strategies’ cards, which read, “Honour thy error as a hidden intention.” Thus the track was born. I would insist that Bowie’s lyrics demand to be understood in relation to a similar discipline of the oblique.

In my humble opinion, authenticity is the curse of music from which we need to cure ourselves. Bowie has helped. His art is a radically contrived and reflexively aware confection of illusion whose fakery is not false, but at the service of a felt, corporeal truth. As he sings in ‘Quicksand’:

Don’t believe in yourself

Don’t deceive with belief.

To push this a little further, perhaps music at its most theatrical, extravagant and absurd is also the truest music. It is what can save us from ourselves, from the banal fact of being in the world. Such music, Bowie’s music, can allow us to escape from being riveted to the fact of who we are, to escape from being us. For a moment, we can be lifted up, elevated and turned around. At their very highest level, songs can, with words, rhythm and often simple, nursery-rhyme melodies, begin to connect up the dots of what we think of as a life. Episodic blips. They can also allow us to think of another life.

As fragile and inauthentic as our identities are, Bowie let us (and still lets us) believe that we can reinvent ourselves. In fact, we can reinvent ourselves because our identities are so fragile and inauthentic. Just as Bowie seemingly reinvented himself without limits, he allowed us to believe that our own capacity for changes was limitless. Of course, there are limits – profound limits, mortal limits – in reshaping who we are. But somehow, in listening to his songs – even now – one hears an extraordinary hope that we are not alone and this place can be escaped, just for a day.

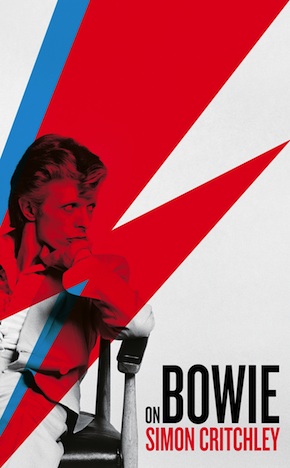

This is an edited extract from On Bowie, published by Serpent’s Tail.

Simon Critchley is Hans Jonas Professor at the New School for Social Research in New York. His books include Very Little… Almost Nothing, Infinitely Demanding, The Book of Dead Philosophers and The Faith of the Faithless. He recently published Memory Theatre, his first novel, and Notes on Suicide. He runs the philosophy column ‘The Stone, in The New York Times and is fifty per cent of an obscure musical combo called Critchley & Simmons. On Bowie is out now in paperback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail. Read more.

Simon Critchley is Hans Jonas Professor at the New School for Social Research in New York. His books include Very Little… Almost Nothing, Infinitely Demanding, The Book of Dead Philosophers and The Faith of the Faithless. He recently published Memory Theatre, his first novel, and Notes on Suicide. He runs the philosophy column ‘The Stone, in The New York Times and is fifty per cent of an obscure musical combo called Critchley & Simmons. On Bowie is out now in paperback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail. Read more.

Author portrait © Noah Kalina