Setting sail

by Jon WalterYour debut novel has been published for a week and it’s the day after the launch party. A landmark day. A time to take a moment, unpack your snack box and admire the view.

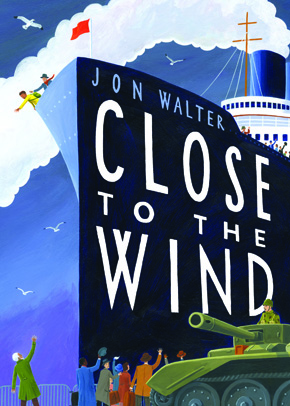

The Sunday Times have made Close To the Wind their Children’s Book of the Week and that’s a great slot, a magnificent achievement for a debut author, so people are already reading your book and they’re enthusiastic – really enthusiastic. They want to know how much of you there is in the story. They want to know where you came from and how you got to be here.

But you’re not even sure where you are.

You’re published – that’s for certain – and it’s a better place than not being published. You can call yourself an author rather than a writer and you have a book that you can wave above your head and shout about. It’s in hardback too. You can rap your knuckles on the beautiful cover and get that lovely bookish thwack suggesting it’s a tome of substance. But where did it come from?

Of course, you always thought you’d be a writer. You stayed behind in the classroom at lunchtime to write your first book, though it remained unfinished because you couldn’t draw pictures that were good enough. And later, at secondary school, you had your poems published in the school magazine and the local paper did that article on you entitled ‘The Schoolboy Poet Who Admits to Being Morbid’.

You were seventeen then and that’s when you stopped writing. Didn’t write a thing again till a few years ago and now everybody you know looks for clues to why you began again.

Perhaps it’s all there in the book? Your sister reminds you that the character called Papa tugs at his beard when he thinks through a problem and that’s something your dad used to do. Your mother wonders how much of you is in Malik – a boy who wants nothing more than to keep his family safe in a time of terrible danger. Is he really based on you? After all, you own a rucksack and a red metal water bottle and a sharp wooden knife with a blade that folds back into the handle. They’re just like the ones in the book.

To add to that, your book could be a play. It has that long opening scene, heavy on dialogue, the whole first fifth of the book. And then there’s the structure and the setting – the first half in the abandoned house and the second onboard the ship. It could almost have been written with an interval. And of course, you studied English and Theatre at Warwick University. Who’d have thought that would come in useful after you dropped out and went to work selling T-shirts on the pier in Brighton?

To take pictures you need to be out in the world, immersed in other people’s lives but not a part of them, whereas when you write a book you have to distance yourself from the world, lock yourself away in a room and try to get into the heads of other people.”

Also, if you think about it, there are those strong images throughout the book. The string of yellow lights along the deck of the ship as it waits at the dockside. The moonlight shining on an empty cobbled street. Weren’t you a photojournalist? And isn’t photojournalism about telling stories but with pictures? But you know that it’s the opposite. To take pictures you need to be out in the world, immersed in other people’s lives but not a part of them, whereas when you write a book you have to distance yourself from the world, lock yourself away in a room and try to get into the heads of other people, to put yourself in their shoes and then say how it feels. So you’re not sure about that one.

And your book is about refugees. It’s so taut with anxiety you could cut it through with a knife. And of course you experienced the Asian tsunami with your family. Three days in a destroyed coastal town till they flew you all out in a rusty old military plane. That flight was more scary than the water. Is that where the book came from? Is that what made you want to write again?

You don’t think so. You have written something based on the tsunami experience but it isn’t this book, it’s another one, half-formed and slumped across your hard drive and you’re struggling to make it work.

Even so – it makes you think.

That experience must have made you decide to write again, to do the one thing you’d always wanted to do. But it wasn’t like that. The tsunami wasn’t the beginning of a career – it was an ending. You stopped being a photographer when you forgot to pick up your camera and you’ve still got the Time magazine cover shot in your head, the picture of the man you were having breakfast with, diving down beneath the water, searching for his children.

You tell yourself that perhaps they’re right. Perhaps the clues do add up to a story that starts at the beginning and reaches a conclusion that appears to have been inevitable once you get there. Sometimes, when you’re on a journey, the path is clear to everyone but you.

But the truth of it is you know exactly how you got here. You began about four years ago when you decided you would try to be a novelist. That involved having to write something and you had an idea for a book that would express your anger at how we as a society view our teenagers, a novel about locking them away aged fourteen, and you decided to sit down and write every day till it was finished. It took six months and you thought it was rather good so you sent it away to agents, just like the Writer’s Handbook tells you to. A few of them replied asking to see the full manuscript and you thought it would be easy but when they all said ‘No’ you realised you needed to learn a lot more about the craft of writing a book.

You went on a Creative Writing course and entered that strange state of education where you don’t think you’re learning anything at all while all the time you are soaking up good advice like a sponge, still working away at your desk every morning for five hours, even when it didn’t seem to be producing results.

After six months of that you go back to your book, because the premise was good and now you have a lot more skills to work with. The new draft finds you an agent, Sallyanne Sweeney, and she’s a good one. But the process of submissions takes a long time – everything in publishing takes such a long time – and you can’t quite get a deal. You were about to be made an offer but then the publisher got taken over by a bigger publisher and it evaporated like so much hot air. But by then you have another book, a little nugget of a story about a boy and an old man trying to escape a war-torn country on the last ship to leave town.

And so you wait… and you wait… and then your agent tells you that a publisher is interested and it isn’t just any publisher, it’s the one you would have chosen all along if only things worked that way. You buy a new pair of trousers for the interview, a pair of thick corduroys that are golden and kept up by buttons and braces. They’ll give you the Oxford look. But when you arrive in Oxford no one is wearing corduroy trousers, they’re all wearing baggy jeans the same as everywhere else. Everyone except your publisher. He wears a red bow tie and he seems to like you. He read your manuscript on his flight back from India and he offers you a deal then and there.

Three weeks after you sign the contract, David Fickling stops being an imprint and sets himself up as an independent publisher and there’s a wrangle over who might publish you and everything takes so long it feels as though it might never happen but it does and what’s more, he wants your book to launch with and so finally after four years of hard work at being an author you actually do become one and your book ships out to all the bookstores. They even have it in the shop down the road.

And so that’s how you got here – wherever it is this is. With a lot of hard work, some patience and a little bit of luck. Sometime soon you might find out where the pathway leads and you hope it’ll be the place you’d imagined when you set out.

And all the other stuff – the bits that make the book feel like it was always there inside you – we’ll that’s the same for everybody, isn’t it? We’ve all got those.

Jon Walter is a former photojournalist who lives in East Sussex. Close to the Wind is published by David Fickling Books. Read more.

Jon Walter is a former photojournalist who lives in East Sussex. Close to the Wind is published by David Fickling Books. Read more.

ma-agency.com