She-devils and evil monsters

by Blessin Adams

IT IS TEMPTING, WHEN READING cases of historical murder, to find comfort in the knowledge that there lies a distance of hundreds of years between us and those dreadful events. We may look upon the laws and attitudes of the early moderns as relics of a bygone age, and perhaps congratulate ourselves that these sorts of things simply don’t happen in our enlightened modern times. It is certainly true that we have come a long way; we do not burn women at the stake for the crime of petty treason, and malevolent witchcraft is no longer a felony offence, to name two obvious examples.

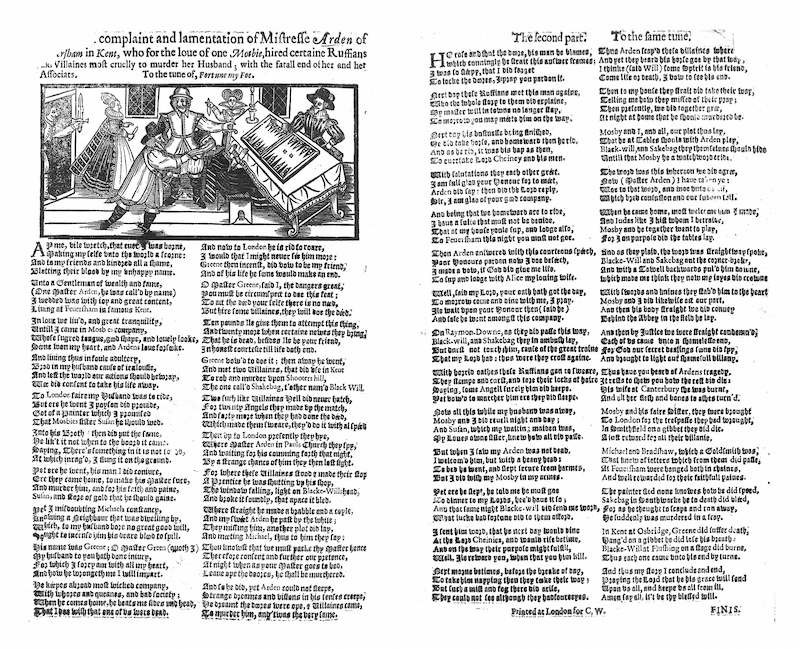

Yet one cannot help but be discomfited by aspects of these cases which seem to be so familiar and near. Like us, the early moderns had a fascination with tales of true crime, and an uneasy disgust with female killers. The rhetoric surrounding murderous women today is not so different to that of the early modern period. Female killers are so often depicted as unnatural traitors of their sex. Women who kill their children are reviled as cold-blooded and devoid of natural maternal instinct; ‘no mother, but a monster’, as the early moderns and we moderns alike would have it. In cases of spousal homicide, the popular moniker ‘black widow’ conjures up images of calculating, mercenary wives who betray their oaths and kill their husbands for material and sexual gain. And while we no longer have a fear of witches and devils, we nonetheless treat female serial killers as uniquely evil and dangerous beings.

The acts of ‘woolvish’ women were so shocking to the early moderns because they defied their understanding of the laws of God and nature, which held women to be the fairer and weaker sex. We moderns likewise have a fascination with women who kill, and our true-crime media are filled with sensational stories of ‘she-devils’, ‘evil monsters’ and ‘unnatural’ mothers. We too have a propensity to dehumanise women who kill, and to isolate them as deviants who have nothing in common with ‘normal’ women. Female killers are especially reviled because they violently, sometimes cruelly, defy our cultural and social belief that women should be kind, nurturing, empathetic and passive.

There are certain parallels to be drawn between how female suspects, then and now, were treated by the media and law enforcement. This is especially evident in the case of Margaret Fernseed, who was accused of driving a knife through her husband’s throat. There was no evidence to prove she was the murderer, however she was taken up and questioned because she had failed to act as a woman must in the wake of domestic tragedy. One cannot help but see similarities with modern cases in which women have been arrested on suspicion of murder because they showed a distinctly unfeminine ‘lack of emotion’ in the stunning aftermath of a homicide. It is commonplace today for newspapers, magazines, podcasts, online communities, the police and courts to scrutinise and condemn the emotional responses of female suspects as being either excessively insincere or insufficient.

Ongoing reforms in the criminal justice system are making it easier to prosecute rape, however the current figures show that change continues to be shamefully slow.”

The chapters in Thou Savage Woman that detail historical cases of sexual assault and rape reveal an appalling lack of progress in our own legal and social attitudes. In early modern England rape was a felony offence, yet it was almost never successfully prosecuted in the courts. Between 1558 and 1700, rape accounted for less than 1 per cent of indictments on the Home Circuit. This figure represents only those rapes that were brought to court. Due to the stigma surrounding victims of sexual violence in this period, it is certain that the majority of rapes went unreported. Today almost all reported rapes fail to reach the courts. In 2023 only 2.6 per cent of rapes reported to police in England and Wales resulted in charges; the prosecution rate was even lower.

Those women in the early modern period who were brave enough to speak out against sexual assault and rape were subjected to hostility and doubt. Their sexual morality was brought into question, and their victimhood dismissed, based on the manner of their dress, and how they acted (or failed to act) preceding, during and after the assault. Married women had no recourse to complaint when subjected to rape because marital rape was legal in early modern England and continued to be so until 1992. Women rarely reported rape, because to do so would cause untold personal distress and irrevocable harm to their reputations. Today five in six women who are raped do not report it to the police, citing embarrassment, humiliation and lack of faith in the police as their main reasons. Ongoing reforms in the criminal justice system are making it easier to prosecute rape, however the current figures show that change continues to be shamefully slow.

Women in the early modern period rarely killed, and when they did so it was usually in the context of extreme provocation, postpartum psychosis or domestic violence. This is especially evident in the case of Mary Hobry, who strangled her husband to death after he had brutally tortured and raped her. When researching such cases I often found myself caught between sympathy and horror. Many women such as Mary committed terrible, violent and fatal acts because they had been driven to it by desperate circumstances. Regardless of their reasons for killing, their crimes could not be mitigated or forgiven. Women such as Mary were granted little sympathy, and were deemed to be vile, inhuman monsters, no matter their motives.

Several cases in this book feature women who were persecuted, prosecuted and sentenced to death even though they were innocent of murder. The women of Windsor and Clewer were hanged for the crime of committing murder by witchcraft, but in truth their joint offence was simply to have been old, poor and unpleasant women. They were reviled because as women they were no longer any use to society: neither maids, nor mothers. They were simply seen as a drain on the community, an inconvenience and a menace. In short, they were unwanted. The same could be said for Joan Peterson, the wise-woman of Wapping, who served as a scapegoat in a feud over a family’s fortune. Her age and sex made her vulnerable to accusation and prosecution. She was powerless, and entirely dispensable to her enemies. I included these cases of innocent women who were hounded to death by their accusers not because they were ‘savage’ women, but because they illustrate so well the fatal force of misogyny in early modern law and society. Today we recognise that these women were not murderers; they were victims. But in their day they were believed to be dangerous killers who posed a legitimate threat to ordinary citizens.

Historically, women have been disadvantaged, mocked and silenced. They have been oppressed by unjust laws, and sometimes cast as criminals if they should breach the boundaries of acceptable female behaviour. Yet women were not universally vulnerable, nor passive. To paraphrase the literary and cultural historian Frances Dolan, a feminist view of history need not be a hunt for victims. Some women killed because they had to; others killed because they wanted to. Throughout history, women have committed terrible deeds and have shown themselves to be equal to men in their capacity for violence and cruelty.

from Thou Savage Woman: Female Killers in Early Modern Britain (William Collins, £16.99)

—

Blessin Adams traded police work investigating crime in the Norfolk Constabulary for academia, tracing the lives and deaths of people in early modern England. She received her doctorate following research in early modern English law and literature at the University of East Anglia. She lives in Norfolk with her husband and two dogs, and is a beekeeper in her spare time. She is the author of Great and Horrible News: Murder and Mayhem in Early Modern Britain (William Collins, 2023). Thou Savage Woman is published by William Collins in hardback, eBook and audio.

Read more

blessinadams.com

@adams_blessin

@WmCollinsBooks