The solace of the strange

by Nydia Hetherington

“A captivating tale of love and loss and finding connection in the most unexpected places.” Nikki Marmery, author of On Wilder Seas

As the threat of a global pandemic grew and when we finally went into lockdown, something happened to our dreams. Telephone conversations, social media posts, virtual meet-ups became places to express the strange effect the virus was having on our subconscious sleeping states. For a while, I’m having the weirdest dreams, seemed to be the opening line of every chat and text. It struck me particularly, as the world of the unsettling, or the just plain strange dream, has long been of interest. In fact, I have waited and even yearned for the fleeting moments when these somnambular visions might take hold. They have been a ballast to my creative life, a touch paper for my imagination. That liminal space between our dream lives and the (sometimes appalling) sameness of the everyday is definitely the place I inhabit when writing stories. In the before times it was, almost inexplicably, my place of safety. And so, when anxiety, fear and panic are at a universal high, when people are trying to make sense of the dreams that have been haunting their waking lives, I’ve found myself to be a dream thief; raiding the dark or odd imaginings of friends and acquaintances, mining their minds for imagery that might somehow take me to the threshold of reality, tip me over into the almost grotesque, and allow me to live in the world of the not-quite-quotidian. Only now, actuality is so disturbing, that solace of the strange is much harder to find. Still, I look, scan the recesses for a place to hide. My debut novel A Girl Made of Air skims the surface of the uncanny, dips a toe into the fabulous, and swims in dark waters. The list below contains works that have, over the years, plunged me into those boundary places. These are some of things I’ve been turning to, to help make sense of my own despair in this new, unrecognisable normality.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin

In this book of short stories by the Argentinian writer whose novel Fever Dream was shortlisted for the Man Booker International in 2017, the space between reality and something else is wildly apparent. Schweblin’s uncanny tales are set in recognisable, domestic settings, but the simple narratives never go the way we expect. Nor do the stories have the satisfying endings we’re used to in fiction, often simply stopping at a point when we think something might happen. The effect is marvellous as the reader is left gasping, mouth gaping and desperate for more. These are modern fables, highlighting the peculiar peeking through the cracks of the mundane.

In this book of short stories by the Argentinian writer whose novel Fever Dream was shortlisted for the Man Booker International in 2017, the space between reality and something else is wildly apparent. Schweblin’s uncanny tales are set in recognisable, domestic settings, but the simple narratives never go the way we expect. Nor do the stories have the satisfying endings we’re used to in fiction, often simply stopping at a point when we think something might happen. The effect is marvellous as the reader is left gasping, mouth gaping and desperate for more. These are modern fables, highlighting the peculiar peeking through the cracks of the mundane.

Read the story ‘Butterflies’ from Mouthful of Birds

‘The Order’ from Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 3

I watched the full seven hours of Barney’s Cremaster Cycle in a cinema in Paris in 2003. I sat alone with about five other people dotted around the near-empty auditorium, and was assaulted by the epic beauty, splendour and oddness that each film hit me with. To say I left the cinema a changed person might be pushing it a bit, but there was a definite shift in my perception of art and its influence on our lives. ‘The Order’ is the final set-piece of Cremaster 3. Set in the Guggenheim museum, the Entered Apprentice makes his way up the five levels of the building, encountering burlesque dancers, heavy rock bands, a woman/cheetah and gallons of molten Vaseline along the way. With connotations of Dante’s rings of hell, played out in sumptuous choreography, costumes and music, The Cremaster Cycle is Barney’s exploration of the artistic experience, using the idea of sexual maturation as a metaphor. The Order is big on production values and a real feast for the eyes. It is also gloriously strange.

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The story’s vivid claustrophobia has an almost magnetic power over me. Even now, if it catches my eye on the bookshelf, I must pick it up. Locked in a room with yellow wallpaper after the birth of her child, the narrator of this short story gradually descends into madness, driven to distraction as the wallpaper design seeps into the ever-growing crevices of her breaking mind. Written in 1892 in lyrical prose, it describes the need for women to have both intellectual and physical autonomy. A dark story often cited to be the first American work of feminist fiction.

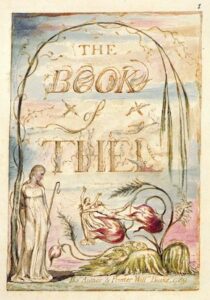

Much easier to get to grips with than Blake’s other prophetic works, this a beautiful poem both in words and pictures.”

The Book of Thel by William Blake

The Book of Thel by William Blake

Immediately recognisable as Blake’s work, this poem consists of eight illuminated plates. Rather than being a shepherdess like her older sisters, Thel roams The Vales of Har, a sort of paradise, looking for the answer to her question, which is essentially, why do living things fade and die? She poses her question to a lily, a cloud, a worm and a clod of clay. The clod of clay gives her an answer but also takes her to the underworld, a place where one day Thel, like all living things, must dwell. While down there, Thel is bombarded by voices who ask all sorts of difficult questions about the meaning of existence, so she runs back to the Vales of Har, away from the darkness (sex and experience) and back to the place of innocence and light. There are so many interpretations of Blake, but what is obvious in Thel is the duality of darkness and light, innocence and experience, eternity over impermanence. Much easier to get to grips with than Blake’s other prophetic works, this a beautiful poem both in words and pictures. If you’ve ever fancied a wander around this great poet’s mythology, The Book of Thel is a good place to start.

Juliet of the Spirits by Federico Fellini

I first fell in love with Giulietta Masina in La Strada, an earlier film also directed by her husband. Here though, we see an older woman. Masina, in the title role, is a middle-aged housewife coming to terms with her spouse’s philandering. Fellini was fond of making films about his inability to be a faithful husband and this is no exception. Only here, the spotlight is well and truly on the neat little housewife as she enters a fantastical world of womanhood, (or rather, a vision of electrically charged sexuality as seen through the prism of busty young women willing to perform at any given moment). I’m aware I sound somewhat disdainful and confess that I have problems with the film’s misogynist narrative. But Masina makes this film, which is a carnival parade of dream sequences and a phantasmagoria of masque and colour. She is so compelling that you cannot help but enter into the world of the film, be captivated by it, and of course, by her. This was Fellini’s first colour film which adds to the dreaminess as Juliet tries to enter into the world of the spirits.

Geek Love by Katherine Dunn

This gorgeous grotesque of a novel, often gritty, often dark, is written in enthralling descriptive prose. It’s the story of the Binewski family, who breed freaks in order to save their travelling carnival show. The ultimate outsider tale, it deals with cults, sexuality, beauty myths and family feuds. Provocative and funny, it’s so electric it crackles as you read.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Oh, the darkness. Oh, the grief. A many-layered story of love and cruelty, mistakes and misdeeds, which when I first read it at fifteen, left me bereft and in love with books forever. I grew up in Yorkshire, so that may have been a factor. But it is was the darkness, the gothic aesthetic that so appealed. The author’s genius was to have written a book full of unlovable characters (even Cathy is a brat), that nevertheless haunts us. And once read, their darkness is forever in your soul. Cathy and Heathcliff are never far from my mind.

Jonathan Miller’s BBC production of Whistle and I’ll Come to You

Sparse and beautifully bleak, this 1968 adaptation of the wonderful M.R. James story is all unease and isolation. Michael Hordern as the aging professor is nothing short of brilliant. How someone so full of desolation can manage to make their performance shine so, is acting perfection. The bedroom scenes install a quiet terror that you will revisit in your own dreams, time and again.

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Epic family saga, political allegory and fable, the book’s narrative moves between generations in breathtaking strokes. Pivoting mainly on the relationship between two women, Allende’s debut novel is packed with magical realism and meaning. Simply put, it is beautiful.

The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, translated and edited by Jack Zipes

All life is here.

Nydia Hetherington was born in leeds and moved to London in her twenties to embark on an acting career. Later she moved to Paris, where she studied at the Jacques Lecoq theatre school before creating her own theatre company. When she returned to London, she completed a creative writing degree at Birkbeck. Her debut novel A Girl Made of Air is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Quercus.

Nydia Hetherington was born in leeds and moved to London in her twenties to embark on an acting career. Later she moved to Paris, where she studied at the Jacques Lecoq theatre school before creating her own theatre company. When she returned to London, she completed a creative writing degree at Birkbeck. Her debut novel A Girl Made of Air is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Quercus.

Read more

@NydiaMadeofAir

nydiamadeofair