The soothsayer

by Michelle Steinbeck

“It’s like a pilled-up journey to hell through scenes taken straight out of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch.” Berner Zeitung

A courtyard, a fountain, a pond with small grey fish. Around it walls, columns, a cloister. At its centre a staircase leads all the way up to the four stoutest columns bearing a roof inscribed with golden lettering.

Flame, undo that which is ephemeral.

Liberated is the eternal.

I climb the steps, pause in front of the cast iron door embellished with small crosses. I knock. Nothing. I knock again. My knuckles now ache. It remains silent. I pull down the heavy door handle, the door can be pushed open, it isn’t locked.

I step inside. The door closes heavily behind me. Deathly silence and gloom. Further back, however, at the end of the corridor, a weak light, a bluish shimmer. My arm held out in front of me, I grope my way towards it. The light is coming from a gap in a low, half-open iron door. I creep towards it and peep inside: an oven! Inside, an old woman sits hunched at a round table covered with red velvet. On the table are playing cards, she slowly turns one, and then another. Her face is lined with furrows and ash eyeliner. She has blue hair and is baring her teeth.

I shudder.

The old woman raises her head and stares through the crack in the door. I freeze and think: she can’t possibly see me out here in the dark.

Oh, there you are, she says and waves me in. Her voice is hoarse and croaky. I hop from one foot to the other, my heart thumps loudly. I prise open the heavy door with both hands. I duck my head and climb into the oven. I take a step towards the old woman. Then I quickly sit down on the suitcase and boldly jiggle my legs.

It’s dark in here too, it’s only around the old woman that an uncanny light radiates, as if she’s glowing; maybe it’s her hair. She wriggles around on the chair and pulls her silver dress up over her knees. Then I see movement in the darkness of her lap. Out crawls a beast, a tiny, wizened, furry crocodile. I gulp, the hairy reptilian creature opens a toxic-yellow eye and snarls, before nestling awkwardly on the old woman’s legs. She splays her gout-ridden fingers in its fur and wraps her own hair around her throat like a stole. Her eyelashes are monstrous and most certainly stiff, like her breasts, which peep out of her dress.

I snatch the fag from her claw, and she hands me the cards. She leans forward, her blue hair sweeps over the floor, her spidery hands paw around under the little table –”

Reading cards is my calling, the old woman says, and offers me a cigarette.

Reading cards is my calling, the old woman says, and offers me a cigarette.

I wriggle around cheekily on the suitcase.

You take yourself very seriously you old crone, I mumble to myself and twist my wet hair between my fingers.

I’m suspicious of young people who have never smoked, the old woman says, as if she hadn’t heard me. Smoking is a way of life.

I snatch the fag from her claw, and she hands me the cards. She leans forward, her blue hair sweeps over the floor, her spidery hands paw around under the little table –

Shuffle and stack the deck, she grumbles, sitting up with a groan, a wooden box in her hands.

I clamp the cigarette between my lips and fudge two piles of cards together. I was never any good at that elegant, fanning sort of shuffling; I wiggle and shove the cards, which reluctantly slide past one another, some fall on the floor. Ash from my cigarette falls on my legs. My eyes water.

The old woman observes me narrowly.

Shuffling is the most important part, she says, you mix your soul into it.

She opens the little box and draws out a small wooden pipe. She lights it and passes it to me. I inhale the sweet smoke, try to feel at one with the cards and purposefully lay down a stack with each exhale. As soon as I release the final cards from my hand, gently brushing against the velvet, the soothsayer snatches the pipe from me and greedily smokes it up.

The figures on the cards blur, I screw up my eyes and try to sharpen their outlines, it makes me light-headed. I straighten my back, and a knock comes from the suitcase – I freeze, and the knock comes again, it really does, from the inside!

Are you listening to me? The soothsayer prods the air in front of my eyes with a crooked finger.

You’re not in the centre, see, she says, poking a card, you ought to be in the centre of things.

I listen. Yes, it’s true, something is knocking in the suitcase, very quietly, I can feel it on my legs. I scrutinise the old woman: has she noticed anything?

You don’t participate, the old woman says without changing her expression, and traces a circle over the cards with her gnarled fingers, even though this is your life.

I kick the suitcase with my heel.

There’s still a lot of child in you, the old woman sighs. A long journey… The father is the problem: You are very close to the father… A separation… Fears.

The soothsayer leaves long pauses and runs her fingertips over the cards. I keep my face blank and listen out for movement inside the suitcase.

The old woman closes her eyes and struggles for breath, her chest rattling: Your fears and your hesitation are not yours… They are your father’s – pack them in the suitcase and give them back to him!

I have to cough all of a sudden: What, I ask coughing, what did you say?

Open your heart, the old woman proclaims, love paves the way for you. The Knave of Hearts is beside you, and the Love Letter. Even the Wedding Bells!

I don’t want them, I say. But what was that about the suitcase?

The crocodile-dog growls, and the old woman chastises me with a dark look. She has scarab-green eyes painted on her lids.

The father stands in your way. He’s blocking the lucky cards. The highest Fortune card is there, and the Triumph card too! Give the father back his suitcase, and you shall be showered with love, fame and gold.

The old woman lays down the final card. Oh, she says, startled, and the creature in her lap stirs and begins to slobber and retch, I see fair men in your future!”

The soothsayer nods contentedly and takes a pull on the dead pipe.

The soothsayer nods contentedly and takes a pull on the dead pipe.

I see, I say, my father. He flew the coop a long time ago – he was afraid of children. I don’t know my father anymore and his suitcase belongs to me now, just like everything else he left behind.

You’re dragging his suitcase around with you, the old woman says exasperatedly, its contents belong to him, not you!

She gives me a piercing look, and then suddenly her eyes begin to roll – first one, and then the other, in different directions.

A red house, the old woman says in a new, crystal clear voice, in the red city. You will find him there. You must hurry.

I don’t say anything. The old woman lays down the final card. Oh, she says, startled, and the creature in her lap stirs and begins to slobber and retch, I see fair men in your future!

I raise my eyebrows, intrigued.

It’s getting worked up, the old women explains and strokes the scaly head of the furry lizard, bending over it and whispering: Of course you’ll inherit everything, I promise, psst, psst.

I close my eyes, the smoke swirls around inside my head.

Do you mean the actual suitcase? I ask slowly.

You know what I mean, the old woman says and clears the cards away in one motion.

My real father?

You should leave now.

I stand, picking up the suitcase with a sigh, and pause in the doorway.

Who or what are fairmen?, I ask.

If you don’t know, the soothsayer says, stroking the reptile’s fur from its head to its tail, you will soon find out.

The storm has left. I make my way through the cemetery and look for the way out; I desperately need something to eat. I start daydreaming about roast chicken drumsticks with wild rice and gravy and small rounds of sweet carrots, and I wander ever deeper into a labyrinth of firs, weeping willows and square box hedges; past war memorials and tombs: penguins, elephants, naked young women gleefully sunning themselves, and, beside them, forlorn muscly men resting their exhausted heads on their knees. I stroke their toes, jealous of the ones they mourn. I go further on and calculate the ages of the dead from the dates on the gravestones, and I cry when I come across men who were as old as my father is. I observe the crows throwing each other nuts and I shuffle and hop and run along the gravel and drag and fling the suitcase high into the air.

In the bracken on the edge of the path, a thin, stone grey man is sitting on a plinth.

Hello, I say, brushing the gravel dust from the suitcase.

The man looks up from his book and regards me through his round spectacles. He has a pointed face and a moustache, one leg crossed over the other like a scholar. He holds himself contemplatively, propping himself up on his elbows, a cigarette held up to his cheek. A dried rose lies in his open book.

The man is silent.

I remember you being taller and, oddly, made of gold.

I sit on the suitcase and peer intently at the man, wondering whether he has blinked.

It’s remarkable, I say, that I should meet you today of all days.

The man doesn’t move a muscle.

Do you remember at all? My father and I, we used to come here every day to visit you. You were his idol. He asked you advice about his book, remember? I almost started writing something today myself. Then there was a mishap and I got distracted. What does it mean, do you think? Nothing? You used to respond to my father, we wouldn’t have kept coming back otherwise. Maybe he still comes here? I’m actually looking for him to give him something. Would you like to know what it is? No? I think I’ll wait here for him. He always had something to eat with him when I still knew him; sandwiches and cake and a thermos of tea – I swear I’m going to die of hunger!

The grey man listens to me attentively, and yet I have the impression that my visit isn’t all that convenient for him.

Yes, I say, that’s life. My friends are getting lines on their foreheads because the overhead projector is too far back and out of focus. I’m getting lines because I’m angry in my sleep. My friends study medicine and scrape fungus off of spleens because the corpses are rotting. And I do nothing all day long. I might as well be a statue: Girl with Suitcase, I’d like that. What about you?

The man on the plinth is silent and thinks, and I stay on the suitcase and try to remember what it was like sitting here in the pushchair while my father read and wrote next to me.

The wind rustles through the trees. I leave the cemetery, taking the suitcase with me.

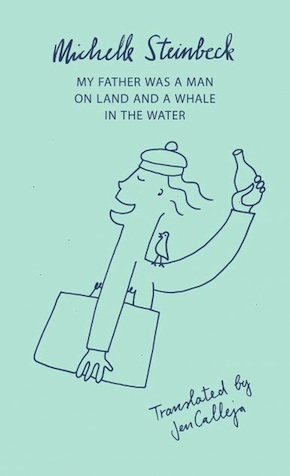

from My Father was a Man on Land and a Whale in the Water, translated by Jen Calleja (Darf Publishers, £8.99)

Michelle Steinbeck was born in Lenzburg, Switzerland in 1990. She writes prose, poetry and drama; reportage and columns. She works as editor-in-chief at Fabrikzeitung and is the organiser of Babelsprech, a forum for young international poets. Her debut novel Mein Vater war ein Mann an Land und im Wasser ein Walfisch was published by Lenos Verlag in 2016 and was shortlisted for the Swiss Book Prize and longlisted for the German Book Prize. She lives in Basel. Jen Calleja’s English translation of the novel is out now in paperback from Darf.

Michelle Steinbeck was born in Lenzburg, Switzerland in 1990. She writes prose, poetry and drama; reportage and columns. She works as editor-in-chief at Fabrikzeitung and is the organiser of Babelsprech, a forum for young international poets. Her debut novel Mein Vater war ein Mann an Land und im Wasser ein Walfisch was published by Lenos Verlag in 2016 and was shortlisted for the Swiss Book Prize and longlisted for the German Book Prize. She lives in Basel. Jen Calleja’s English translation of the novel is out now in paperback from Darf.

Read more

@DarfPublishers

Author portrait © Affolter/Savolainen

Jen Calleja is a writer of fiction, creative non-fiction and poetry, and a literary translator from German into English. Her reviews, articles and interviews have been published in the Times Literary Supplement, Brixton Review of Books, The Quietus, The New Statesman and elsewhere. She also teaches creative writing and literary translation for the British Library, The Poetry School, universities and schools. She is based in London.

jencalleja.com

@niewview