Squinting at DeLillo

by Brett Marie

“Daring… provocative… exquisite… captures the swelling fears of our age.” Washington Post

“I thought, Is this the world as it truly looks? Is this the reality we haven’t learned how to see?”

Artis Martineau, Zero K

Those who came of age in the nineties will no doubt remember the Magic Eye craze. Many will recall the fraught minutes spent studying these seemingly-abstract images, trying to ‘relax’ our vision – to defocus, or deep-focus, depending on whose advice we took – before the 3-D autostereogram appeared in front of us. For some, the computer-generated apparition never materialised. These unlucky few had to look on a meaningless jumble of colour and accept one of two realities: their friends were lying and there was nothing to see, or they were freakishly incapable of seeing an image that was clear to everyone else. It was a choice between paranoia and shame.

I know those feelings all too well. Though it took me just a few minutes to spot the mother whale and her calf on my friend’s living-room wall all those years ago, that frustration, that bewilderment, came back to me not long afterward when I picked up a copy of Underworld at a Los Angeles flea market. For more than a decade thereafter, Don DeLillo became my Magic Eye.

I had read a rave about Underworld in Time magazine. I knew about the award nominations (National Book Award, Pulitzer Prize, you name it), and I’d heard the breathless whispers about the Great American Novel. Taking the book home, I tore into it, and for seventy-five pages I was a believer, right there with DeLillo as he set the scene of the famous one-game play-off between the Dodgers and the Giants at New York’s Polo Grounds in October 1951.

But Underworld‘s prologue (originally published years earlier in Harper’s as ‘Pafko at the Wall’) was apparently an aberration, one that seemed increasingly like a mirage in my rear-view mirror the further I slogged up the mountain of prose that followed. The remaining 750 pages featured a cavalcade of minor characters, trudging through half a dozen storylines, only some of which seemed to connect with each other, none of which connected with me. The dialogue felt wooden, the scenes lacked urgency, and I couldn’t for the life of me find a theme running through it that wouldn’t collapse under the weight of so many words.

But this was DeLillo’s magnum opus, an acclaimed book by an acclaimed writer. And clearly the guy knew how to string a sentence together: the one thing that got me through to Underworld‘s back cover was the rhythmic ease of its prose. Surely I’d missed something. Determined to keep an open mind, I dropped an hour’s wages on White Noise, the other DeLillo ‘masterpiece’ I’d heard about. But White Noise was another struggle for me. I could laugh at DeLillo’s satire on consumerism in the late twentieth century, and I could sympathise with Jack Gladney’s fear of death, but beyond that I was stumped as to why I should care about Jack, his wife Babette or eccentric colleague Murray.

Years later, inexplicably drawn to DeLillo’s name in bold type on a library shelf, I took a stab at his 9/11 novel Falling Man. The book landed back on the shelf five minutes later – the symptoms of White Noise and Underworld were on full display in the opening chapter. I just could not sympathise with characters I found so hollow, could not follow another scene of speech-tagless dialogue between characters who spoke in the same voice as the narrator, could not work up the curiosity to turn another page and find out what might happen next.

But in interview after interview, article after article, my literary heroes continued to drop his name. David Gilbert talked at length about meeting the man, and how delighted he was with DeLillo’s persona. Another article referred to Dana Spiotta as his protégé. If an author influenced me, chances were that DeLillo influenced them. And so when I read about his upcoming novel (his sixteenth), Zero K, I found myself anxious to give it a try – it was a nut I had to crack.

Open Zero K and you find yourself in a futuristic compound in the middle of nowhere. Jeff Lockhart has come here at the behest of his filthy-rich estranged father, to say goodbye to the old man’s second wife Artis, who is dying from Multiple Sclerosis. She is to be cryogenically frozen, in order to be brought back to life once medical science has come up with a cure for her condition. I enjoy a good piece of science fiction, and so I took the book’s premise as a good sign. But DeLillo was still DeLillo, and for a few chapters I found myself rolling my eyes at the unimaginative setting (the compound itself is a maze of colour-coded hallways, each one lined with doors which might or might not lead anywhere), characters who seemed hardly to care about each other, and dialogue so expository that I wondered if the quotation marks were typos.

By Chapter Three I was ready to give up, set the book down, accept that I just didn’t have the DeLillo Receptor Gene, and get on with my life. But that very evening, completely oblivious to my little crisis, my wife Roxanne decided she wanted to watch Rainbow Bridge.

Somehow the glow from Rainbow Bridge was still shining when I picked up Zero K again, because from the first word, every scene now seemed cast in a different light.”

Not so much a movie as a low-budget two-hour infomercial for a late-sixties New Age commune in Hawaii, Rainbow Bridge might appear to have little in common with the work of America’s Greatest Living Writer. Indeed, while you’ll find multiple copies of all DeLillo’s novels on the shelf in any bookstore, Rainbow Bridge exists only as a cut-out bin-ready DVD, in print today only by the grace of Jimi Hendrix, who appears in an eight-minute concert at the film’s climax (it’s not surprising that our copy’s cover is a picture of Hendrix in all his onstage glory). Thank goodness for Chapter Selection, because without it, the average viewer would have to sit (or fast-forward) through scene after scene of plotless, aimless, pseudo-religious and pseudoscientific ramblings (I can only assume the lines were improvised), from an awkward army of proselytising non-actors, to reach Jimi in action.

But Roxanne doesn’t need the remote. She has watched the whole thing many times. She enjoys this movie. And although I have in the past been less than subtle about my unwillingness to enjoy it with her, I’m now ready to thank her for ever showing it to me. Because something happened when she put it on this time.

As the TV went dark for the opening (a five-minute sermon about UFOs and spirituality, voiced over a black screen), I made like I had to tidy up and left the room. But a while later I came back, I don’t remember what for. I happened to glance at the screen, and there in the frame was something that, for all the times I’d watched this movie, I’d never seen before: looming behind the babbling players was a spectacular Hawaiian landscape. For several seconds I watched, ignoring the scene but riveted by the beauty of this natural wonder. I was still watching when the scene changed, the two characters now trekking up a windswept mountainside. I’d found something beautiful in this movie, and its glow lasted past the last outdoor frame, so I didn’t mind so much when the action shifted indoors and the cast began talking about aliens and the body-temple. The movie was still far from coherent, but I was suddenly able to take it in and hold my tongue, when on another night I might have had a snide remark ready for every other line. Listening to the stilted dialogue, watching what passed for action, on this umpteenth viewing I finally detected something resembling a storyline. And if at times the spiritual talk went over my head, at least every few minutes there was a mountain to look at.

And somehow the glow from Rainbow Bridge was still shining when I picked up Zero K again, because from the first word, every scene now seemed cast in a different light. The setting was still drab, the characters still shallow, the dialogue sloppy. But behind every sentence loomed a larger entity, the contours of which I gradually began to grasp. The story had some substance; it felt somewhat poignant to watch Ross Lockhart decide to undergo the freezing procedure with his wife, only to have second thoughts a couple of chapters later. But more than that, hovering behind this ostensible plot, far more compelling to me, loomed a very basic, elemental question: what is life without death?

Don DeLillo isn’t a novelist, I see that now. He is a philosopher. Zero K is just a framework for him, something on which he can hang his existential musings. Science fiction, by nature a genre of speculation, suits his purposes well. His thoughts are deep, important, and the story he presents as their façade cannot, by necessity, overly engage us, or it might smother the real points he wants to put across. The antecedents for a DeLillo novel aren’t Austen or Orwell; they’re Plato, Nietzsche. It doesn’t matter that Zero K’s characters sometimes just stand and recite the author’s assertions – that’s all I remember them doing in Plato’s Republic (and I enjoyed Zero K a good deal more).

Will Zero K measure up in the eyes of seasoned devotees? I’m not the one to say. But after my epiphany, I will go back and reread White Noise, Underworld, maybe even Falling Man. I don’t expect to suddenly fall in love with any of the characters, but I’m now certain there’s something beautiful lurking between the lines I once found so bothersome. I can picture that elusive, nebulous thing waiting to be discovered, if I only cross my eyes a certain way.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

Zero K by Don DeLillo is published in hardback by Picador on 19 May, with eBook editions available now.

Zero K by Don DeLillo is published in hardback by Picador on 19 May, with eBook editions available now.

Read more.

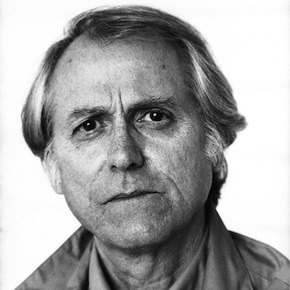

Author portrait © Joyce Ravid

“One of the most mysterious, emotionally moving and formally rewarding books of DeLillo’s long career… I finished it stunned and grateful.”

Joshua Ferris, The New York Times Book Review