Trying to tell a stranger about rock ’n’ roll

by Brett Marie

“That warmth, that authenticity, those stories… masterfully told.” Annie Nightingale

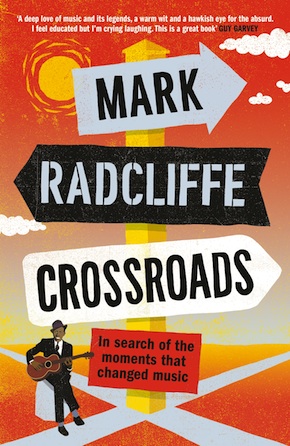

Before I start in on Mark Radcliffe’s romp through pop history Crossroads: In Search of the Moments that Changed Music, I need to make a confession: prior to reviewing this book, I had never heard of Mark Radcliffe. I know it’s wearing pretty thin to use the excuse “I’m new here” after thirteen years living in England, but there it is, with my apologies. I had to check Wikipedia to learn of Radcliffe’s many stints as a presenter on BBC radio and television, and of his successes as a musician and memoirist. I came away impressed.

Here’s a little factoid I discovered while I was there: Radcliffe has received an honorary doctorate from the University of Bolton. And that’s a good thing, I must say, because if his methodology in Crossroads is anything to go by, he’d have trouble getting awarded one the normal way.

Radcliffe’s stated aim for this book is to explore pivotal moments in the lives of pop music’s foremost talents, and how those events changed things not only for those individuals, but for the wider culture as well. His curiosity on the subject stems from having come to a crossroads of a sort in his own life: turning sixty, losing his father, being diagnosed with tongue and throat cancer, all in rapid succession. He pushes off from the right place, using his opening chapter to take a real-life pilgrimage to the One True Crossroads of pop culture, the intersection of Highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, where Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul to the devil to become the ‘King of the Delta Blues Singers’. But the route he takes from there is erratic, to say the least. His choices of what constitutes an important turning point are arbitrary at best, and often before he can make his case about an event’s significance he loses focus, allowing his thoughts to wander past his point and into the verbal culs-de-sac of some aside or other, about some other band at some other time.

This attention deficit isn’t just thematic. On a sentence-by-sentence level, Radcliffe approaches his prose like a cat on a ball of yarn. At times he pounces on a quick piece of wit. Just as often he circles an idea, bats at it, then wanders off before his sentence is through. His reverence for punctuation in general, and commas in particular, is intermittent, which becomes a problem for those of us trying to keep up with him across sentences that can take up half a page. His modifiers don’t just dangle, they positively twist in the wind. At one point he tells us, “Lying in bed under my swirly-patterned yellow and lime green single duvet cover, [John] Peel played ‘I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend’.” The sentence leaves this grammar pedant to wonder what a Radio One DJ was doing spinning records from under Radcliffe’s bedding.

Radcliffe’s saving grace is this infectious enthusiasm. The subtext of virtually every run-on sentence in Crossroads is simply: Isn’t all this music fantastic? Aren’t we lucky as fans that all these moments happened?

His fact-checking is lax. At least once he presents an urban legend as truth. 10cc did not, in fact, get their name from anything resembling the average volume of a male ejaculation, which is less than 5cc (I looked it up). And he’d flunk a geography exam on the English Midlands if he insisted, as he does here, that “the geographical location of Birmingham leaves it without another rival city within spitting distance.” Tell that to hometown fans of the Specials and Coventry’s famous 2-Tone label, and they’ll spit back at you to prove you wrong.

But formulating a concise and watertight argument is clearly not Radcliffe’s goal. And frankly, thank goodness. Who wants to read stories of Black Sabbath or Green Day written in stuffy, scholarly tones? Rather, Radcliffe is the stranger who sidles up to you in the crowd at Glastonbury, while you wait for the crew to solve some technical glitch before the next band comes on. Plastic beer cup in hand, half-smoked blunt smouldering at his fingertips, Radcliffe wants only to pass the time between sets with a little conversation.

As often happens with characters like this, he has a lot to say. It goes without saying that, as his ideas tumble out, he’ll have trouble giving weight to the really important ones (a chapter devoted to the disco craze plays up the MAGA-ish excess of the ‘Disco Sucks’ backlash at the expense of the real ‘crossroads’ moment when DJs flipped a Gloria Gaynor single over to its B-side, making a mega-hit out of ‘I Will Survive’ and proving that the movement could produce tracks that were substantive – even empowering – beyond the usual dance-floor fodder). And it’s one of the built-in flaws of literature that there’s no way to call bullshit on Radcliffe in midsentence, and correct him when we disagree on which moments rise to the standard of his premise: “Come on, pal! All this talk of Fairport Convention, and just a few lines on all of Motown?”

But Radcliffe has a couple of qualities that most of these types lack. First among these is a decent sense of humour, often deployed at his own expense. In an anecdote about his visit to Clarksdale, when an eccentric cab driver asks him and his cagoule-wearing friends, “So, have you guys been laid?”, the author quips: “Perhaps he glanced at us and wondered whether we’d been laid ever.” Moreover, he serves up music-nerd trivia with the joviality of a fellow fan rather than the smugness of a know-it-all showing off. He’s endearing, charming rather than off-putting, and his conversational tone begs for the reader to join in his game. Before I was halfway through the book, I’d thought of three moments of my own which I waited to see if he’d mention, and which I wished I could have called out to him when he didn’t:

- Chuck Berry’s lyric switch from “a coloured boy” to “a country boy” named Johnny B. Goode in his most famous single, thus making his song’s hero more racially ambiguous, and therefore a more universal role model for aspiring rock stars for generations to come.

- Bo Diddley’s discovery, while trying to sing and play a Gene Autry song at the same time, of his signature strumming style, which would become the propeller for hits by everyone from Buddy Holly to U2, from the Rolling Stones to George Michael.

- Elvis Presley’s resurrection on national television, the 1968 Comeback Special, in which he proved that rock ’n’ roll singers could have careers – and remain culturally relevant – past the age of thirty.

I like to think Radcliffe would hear these suggestions and exclaim “Right on!” But perhaps he’d question my reasoning, or my facts. To be honest, I’d welcome either response. Above all, Radcliffe’s saving grace is this infectious enthusiasm. The subtext of virtually every run-on sentence in Crossroads is simply: Isn’t all this music fantastic? Aren’t we lucky as fans that all these moments happened? And the answer to both of these questions is of course an excited Yes! I’d be happy to stand in the mud next to Radcliffe and argue over rock lore while roadies scurry around checking microphones, just as I’m happy to read his thoughts on what’s come before while we all wait for the next big thing in music to come along and blow us all away.

Mark Radcliffe is a broadcaster, writer and musician. He is the author of Showbusiness, Thank You For the Days, Reelin’ in the Years and the novel Northern Sky. He lives in Cheshire. Crossroads is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Canongate.

Mark Radcliffe is a broadcaster, writer and musician. He is the author of Showbusiness, Thank You For the Days, Reelin’ in the Years and the novel Northern Sky. He lives in Cheshire. Crossroads is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Canongate.

Read more

@themarkrad

Author portrait © Paul Langley

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, PopMatters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979