Subverting the idea of The One That Got Away

by Katie Bishop

Of all the great romance tropes – friends to lovers, forbidden romances and love triangles – there’s one that I’ve never been able to resist. From Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth in Persuasion to Jay Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby, the idea of The One That Got Away has always pulled at me on some deep and inescapable level. And why wouldn’t it? Tales of lovers separated by circumstances outside of their control but destined to be together tend to have all the hallmarks of a good story. The undercurrent of fate. The pain and longing of separation. The catharsis of reunion. There’s a reason why so many writers – from Murakami to the Brontë sisters – have drawn on the theme of long-separated lovers in their work.

The One That Got Away carries such a profound mythology and cultural currency that almost everyone has one – ask most of your friends about their One That Got Away story and they’ll inevitably become misty-eyed. They’ll tell you about a university boyfriend, or a summer fling that always made them wonder “what if?”

Psychologists will tell you that we have a habit of looking at these past relationships through rose-coloured lenses. More than about actually wanting to be with somebody else, The One That Got Away myth offers us a sense of possibility. It reminds us that there are other realities that we might have chosen. The fantasy of another life that we could have lived.

They’ll also tell you that memories are a way of making meaning out of our past. Sometimes, creating stories about a so-called One That Got Away is a way of sifting through complicated and sometimes messy experiences of life and love. They simplify some of the things that we might otherwise struggle to name. In life, as in novels, we like to see character arcs and plot progression. We want everything to have meaning, to be able to label certain parts of our story as clearly as we categorise fiction. There’s a reason why, for thousands of years and across numerous cultures, people have had concepts of soulmates, or have had specific ideas of how first love looks and feels. The One That Got Away is another story that we tell ourselves to better understand our experiences.

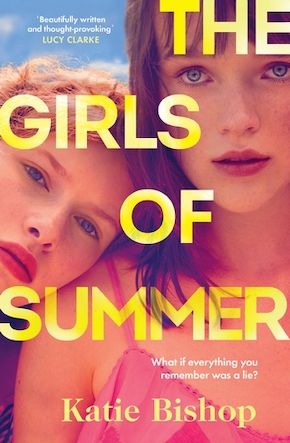

In most One That Got Away novels – from The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller to Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – the reader roots for the separated lovers to come back together. But in my novel, The Girls of Summer, I wanted to upend this narrative. I wanted to explore how these powerful cultural myths can sometimes lead to us misnaming, or even misremembering some of our most profound and complicated experiences. After all, it’s easier to fantasise that you might be someone’s One That Got Away than to admit that they broke your heart without a backward glance.

Through Rachel’s story, I wanted to explore questions that many women have been forced to ask since the #MeToo movement prompted a huge reckoning of our past romantic and sexual experiences.”

In The Girls of Summer, our protagonist Rachel has always believed that a summer romance she had as a teenager with a much older man was her great love story. She views him as her One That Got Away, even though she hasn’t seen him for almost twenty years. But when she tries to track him down, she is forced to unpick a web of mis-memories and trauma surrounding the magical summer months they spent together. Ultimately, Rachel must confront how the myth of The One That Got Away kept her captivated for so long, when the truth of her relationship was in fact something entirely different.

Through Rachel’s story, I wanted to explore questions that many women have been forced to ask since the #MeToo movement prompted a huge reckoning of our past romantic and sexual experiences. What happens when a romance you have idealised for your entire adult life turns out to have been something very different from how you imagined it? How does it feel to realise a narrative that you have shaped much of your life around is false? When the glossy naivety of youth is stripped away, and you start to understand your greatest love story as something altogether darker?

The stories we tell ourselves often oversimplify complex human feelings and experiences. And although I’ve always been enamoured by a good One That Got Away tale, I wanted to challenge the idea that the relationships that draw us back the most are also the ones that are the truest or most meaningful. In fact, sometimes the most damaging and toxic relationships are the ones that pull at us for the longest time. Sometimes, we can convince ourselves that people who have hurt us deeply are the ones that care for us the most. Sometimes there’s a very good reason why you are no longer with the person who you still think about now and then late at night. Sometimes, as we see with Rachel, it’s easier to tell ourselves that a love was great and good and beautiful rather than confronting the truth.

The last few years have seen a wave of #MeToo-inspired books. From My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell to Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams, we are increasingly seeing female sexuality and the way that it is viewed, abused and reclaimed portrayed in fiction. The Girls of Summer deepens this conversation, asking how the myths that surround love and relationships perpetuate these abuses – and how they sometimes keep women in the thrall of their abusers. Because the more that we disrupt these narratives, the more that we open up space for women to tell and create their own stories.

—

Katie Bishop grew up in the Midlands before moving to Oxford to work in publishing in her early twenties. Whilst working as an assistant editor she started writing articles in her spare time, going on to be published in the New York Times, Guardian, Independent and Vogue. In 2020, Katie moved back to the Midlands, and now lives in Birmingham with her partner. The Girls of Summer, her debut novel, is published by Bantam and Transworld Digital in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

katiebishopwrites.com

@WhatKatieBWrote

katiebishopwrites

@TransworldBooks

Author photo: Trunk Archive