Suzy

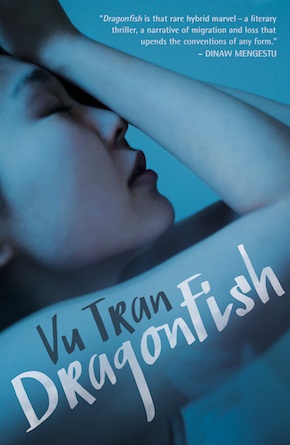

by Vu Tran

“A debut novel of uncommon artistry.” Tom Perrotta

It was three in the morning and dark in my apartment. I stood half naked behind the front door, peering through the peephole at my vacant porch. My voice had come out small and childish and like someone else’s voice calling from the bottom of a well.

“Who’s there?” I said again, louder, more forceful this time. The porch light flickered but I could see only the lonely rail of my balcony, the vague silhouette of trees beyond it.

I grabbed my officer jacket off the kitchen counter and slipped it on. I steadied the gun behind me, then slowly opened the door and let in the cool December air. The hair on my chest and legs bristled. I stepped onto the porch. No one on the stairwell. No one by the mailboxes. A sweeping breeze from the bay made my legs buckle. I peered over my second-floor balcony. In the darkened courtyard, strung over the elm trees, a constellation of white Christmas lights swayed.

I returned inside and locked the door. I crawled back into bed, back under the warm covers as though wrapping myself in the darkness of the room. The two knocks that had awakened me resounded in my head, this time thunderous and impatient and so full of the echo of night that I asked myself again if I had heard anything at all. Could a knocking in your dreams wake you?

Some minutes passed before I placed my gun back on the nightstand.

“No one out there to hurt you but yourself,” my father, a devout atheist, used to tell me. I never took this literally so much as personally, because my father knew better than anyone how selfish and shortsighted I can be. But whether he was warning me about myself or just naively reassuring me about the world, I have chosen, in my twenty years as police, to believe in his words as one might in aliens or the hereafter. They’ve become, it turns out, a mantra for self-preservation. Cops get as scared as anyone, but you develop a certain fearlessness on the job that you wear like an extra uniform, and people will know it’s there like your shadow slipping its hand over their shoulder, and intimidated or not they’ll think twice about hurting you. It’s an armor of faith, a wish etched in stone. Go ask a soldier who’s been to war. Or a priest. Or a magician. Without it, without that role to play, everything is a cold dark room in the night.

My phone rang at six the next morning, an hour after my alarm woke me. I was already in uniform, coffee cup in hand and minutes away from walking out the door. As soon as I answered, the phone went dead – just like the previous morning.

Once inside I noticed an unfamiliar smell, like burnt sugar, like someone had been cooking in the apartment, which I never do. In my bedroom, the pillows on the bed were oddly askew.”

I went to the window and peeked through the mini blinds at the parking lot below. No one was up and about at that early hour, and the morning was still a stubborn shade of night. I made a fist of my left hand, unfurled it. My fingers had healed along with the pink scar on my wrist, but a warmth of unforgotten pain bloomed again. I stood there gazing at the lot until I finished my coffee.

Two days before this, I had come home from my patrol and found the welcome mat slightly crooked. Easily explainable, I figured, since any number of people – mailman, deliveryman, one of those door-to-door religious types – could have come knocking during the day. But once inside I noticed an unfamiliar smell, like burnt sugar, like someone had been cooking in the apartment, which I never do. In my bedroom, the pillows on the bed were in the right place but looked oddly askew, and one of my desk drawers had been left an inch open. It’s always been the little things I notice. Show me a man with three eyes, and I’ll point out his dirty fingernails.

The same smell greeted me the next evening as soon as I opened the front door. It followed me through the living room, the kitchen, the bedroom, the living room, the kitchen, fading at times so that I found myself sniffing the air to reclaim it, as I did as a boy when I roamed the house for hours in search of a lost toy or some trivial thought that had slipped my mind. Then the smell vanished altogether. Half an hour passed before I finally went to the bathroom and saw that the faucet was running a thin stream of water. I shut it off, more than certain that I had checked it before leaving that morning, something I always did at least twice.

I closed all the window blinds and spent the next two hours combing through all my drawers and shelves, opening cabinets and closets, searching the entire apartment for something missing or out of place, altered in some way. I knew it was ridiculous. Why would they go sifting through my medicine cabinet or my socks? Why move my books around? I suppose checking everything made everything mine again, if only temporarily.

That night I went to bed with my gun on the nightstand, something I hadn’t done in nearly five months, since those first few weeks back from the desert.

I’d been trained on the force to trust my gut, or at least respect it enough to never dismiss it; but it crossed my mind that I was imagining all this, that in the previous five months I’d been glancing over my shoulder at shadows and flickering lights. You fixate on things long enough and you might as well be paranoid, like staring at yourself in the mirror until you start peering at what’s reflected behind you.

A drowsy fog crawled in from the Oakland bay, a cataract on the sunset, the day, which now felt worn.”

When the phantom door knocks awoke me that same night, I lay in bed afterward and waited. I was that boy again, hearing the front door slam shut in the middle of the night and measuring the loudness and swiftness and emotion of that sound and whether it was my mother or father who’d left this time, and then waiting for the sound again until sleep washed away the world.

The lesson of my childhood was that if you anticipate misfortune, you make it hurt less. It’s a fool’s truth, but what truth isn’t?

When I got home the following evening, I stayed in my car and stared for some time at the dark windows of my apartment. I was still in uniform but driving my old blue Chrysler. A drowsy fog crawled in from the Oakland bay, a cataract on the sunset, the day, which now felt worn. ‘Empty Garden’ played on the radio, a slow sad song I hadn’t heard since my twenties. I remembered the old music video, Elton John playing a piano in a vacant concrete courtyard amid autumn leaves and twilight shadows. I sat back and scanned the complex of buildings surrounding me and thought of Suzy and the flowers that decorated every corner of our old house, and at the pit of me was not sadness or anger but the hollowness of forgetting how to need someone.

Three kids on bicycles glided past my car through fresh puddles left by the sprinklers. Some twenty yards away, an elderly man strolled the courtyard with his Chihuahua like a scared baby in his arms. In the building that faced me, three college guys were leaning over their balcony, smoking and leering at a pretty redhead who passed below them with a baby stroller. Then I saw a skinny Asian kid – a teenager – walk in front of my car, turn, and approach the window. He smiled and gestured for me to roll it down. His hands looked empty. He was wearing a Dodgers cap and an oversize blue Dodgers jacket zipped all the way to his throat. His smile was like a pose for a camera, and when he bent down to face me, he was all teeth.

I cracked open my window.

“Hello, Officer,” he said. “Nice evening, huh?” He slipped me a folded note through the crack, and before I could say anything, he jogged away around the corner of the building.

I recognized the yellow paper, the Oakland PD logo, ripped from the notepad on my kitchen table. The words were neatly printed in red ink: We’ve come from Las Vegas. Leave your gun in the car and come into your apartment. We just want to talk. Follow these instructions and no one will be harmed. That last line lingered on my lips as I refolded the note and slipped it into my breast pocket, glaring again at the windows of my apartment. Why would they warn me? Why give me a chance to walk away? I considered calling in for help, but had to remind myself that if I hadn’t told a soul about what happened five months ago, there was no explaining it now, at least not to anyone who could help. I could have driven away too, but I’d done that before and it had only led me here, to this moment. Or so I suspected.

And that was really the thing: whatever it was, I just needed to know. Nothing more exhausting than the imagination.

I pulled my gun out of its holster and made a show of holding it over the steering wheel before placing it into my glove compartment.

Walking away from the car felt like leaving a warm bed. I had lived in the complex for over two years, ever since the divorce, and liked it well enough, but only then, as I was trudging up the path toward my apartment, did I see how its tranquil beauty seemed like a postcard of someone else’s life: the ivory stucco buildings leaning into shadow, hugged by tall trees and trimmed bushes and small perfect squares of lawn drowned now, even in winter, by the evening sprinklers. I began my climb up the stairwell. I noticed for the first time how craggy the stone steps were, how awfully they’d scrape at your skin if you were to go falling down the stairs.

Not sure what to do at my own front door, I knocked. There was no answer, so I slowly turned the knob. The door was unlocked. It opened into darkness. As soon as I stepped inside, the lamp in the living room clicked on.

There were two young Asian men standing side by side in front of the TV set. The taller one spoke up in perfect English: “Close the door, please.”

I remained in the doorway and gripped the doorknob, one foot still lingering on the porch. I remembered the last line of their note and took another step inside, nudging the door shut with my heel.

I saw no sign of a gun on either yet, which bothered me more than if they’d already had one pointed at my head. They were not nervous, though they expected me to be.”

It’s always difficult to tell with Asians, but the two of them could have been no older than twenty-five. The short one sported a goatee and slick hair and stood ashing his cigarette into my potted cactus, his wiry frame wrapped in a shiny black leather jacket. The other one, buzz-cut and sturdy in jeans and a bomber jacket, was a foot taller and moved that way, having just, without a word or glance, handed his binoculars to his partner, who dutifully set them atop the TV. I saw no sign of a gun on either yet, which bothered me more than if they’d already had one pointed at my head. They were not nervous, though they expected me to be. The goateed one, like their messenger outside, acted happy to see me; he had nodded when our eyes met, right after the lamp flickered him into existence. But it was the taller, stoic one who again spoke.

“You are Officer Robert Ruen.”

“Who’re you? Why are you in my home?”

“I’m sure you can guess. You came up, didn’t you?”

“Did I have a choice?”

He said something to the goateed kid that I did not understand, but I knew for certain then that they were Vietnamese.

Casually, the kid put out his cigarette in the cactus pot and approached me with a sly grin and his palms out like he wanted a hug. “If you don’t mind, Mr Officer, I’m gonna search you right now. Wanna make sure we all on even ground.”

I hesitated at first, not sure yet whether I should cooperate or play dumb and tell him to search himself. His pleasantness both irked and intimidated me. I put my hands on the front door and let him pat me down. He was half my size, but his hands were solid, with weight and intention behind them. Satisfied, he gestured for me to make myself comfortable on my own couch, which I did after quickly sniffing him and smelling nothing but cigarettes.

They’d been waiting for some time. A couple of my travel magazines lay open on the coffee table beside two open cans of Coke from my fridge, and the TV remote sat atop the TV instead of its usual resting place on the arm of the sofa. I was surprised they hadn’t kicked off their shoes and made coffee.

The kid watched me as I, by force of habit, slipped off my loafers and set them neatly to the side. He chuckled lazily and turned to his partner. “I think we dirtied up his carpet.”

His partner looked at his watch, then at my shoes. Again he spoke in Vietnamese. The kid threw him an exaggerated frown, but he repeated himself and was already silently unlacing a boot. A moment later they had both tossed their shoes onto the tile floor by the front door.

“Our Christmas present to you,” the kid said to me in his white socks.

“How did you get in here?”

“Through the front door. Simmer down, Mr Officer. We just waiting for a phone call.” He shut up for the moment, waiting like his partner.

On the wall behind them hung the samurai sword I had bought ages ago at a flea market for forty bucks. I had unsheathed it once or twice to admire it, and now wondered how sharp it actually was.

“Hey,” the kid said, struck by something. “I got something else for you.”

Though I was going nowhere, he gestured for me to remain seated. He arched his brow mischievously at me, as if at some eager child at a birthday party, and reached into his jacket pocket. I held my breath as he pulled out another cigarette, which he put to his lips. From the other pocket, he revealed a silver flask. Holding out an index finger like a perch for a bird, he carefully poured the contents of the flask over the length of it. He raised it to his face and flicked his lighter. The finger ignited in a calm blue flame, which he promptly used to light his cigarette. He held up the finger like a candle, blew a lazy plume of smoke over it, and watched it burn itself out as he flashed his jack-o’lantern grin. I couldn’t tell if he was trying to scare me, entertain me, or make fun of me.

His partner looked on with glassy, tired eyes. We exchanged an awkward glance before he looked away as if embarrassed by this brief talent show.

His cell phone chimed and he brought it carefully to his ear, nodding at the kid to take a post by the door. He spoke Vietnamese into the phone as he gave me another once-over. He moved into the hallway between my bathroom and bedroom, murmuring into the shadows. After a minute, he came back and handed me the phone.

The line was silent.

“Yes,” I said.

“You. Robert Ruen.” It was a declaration, not a question – an older man’s voice, loud and somehow childish, the accent unmistakably Vietnamese. “Say something to me.”

“What do you mean?”

“You. Your voice, man – I don’t forget thing like this.”

It might have been his broken English or how quickly he spoke, but he sounded something like a puppet. He was smoking, sucking in his breath fast and exhaling his impatience into the phone.

“You’ve made a mistake,” I said.

“You got bad memory? You know who I am.”

“I have no idea –”

“Las Vegas, man. I know you come here. You think I’m dummy I not figure out?” He snorted and spat, as if to underline his point. “In Vietnam, we say beautiful die, but ugly never go away. For policeman, you do some bad fucking thing. You know how long I wait to talk to you? I been dream about this. I see your face in my fucking dream.”

My houseguests were stirring. The tall one slowly unzipped his jacket, and the kid drifted behind me. I could still see curls of his cigarette smoke.

I spoke calmly into the phone, “What do you want me to say?”

“Tell me.”

“Tell you what?”

“You fucking know.”

“I don’t know anything about anything. Just what the hell are you talking about?”

He sounded like he was thinking. Then he replied, as if repeating himself, “Suzy.”

The name drained me all at once of any effort to deny its importance. It was like he had slapped me to shut me up.

I think back on it now, and this was the moment I felt the full weight of the things I’d already lost – the last moment before everything that would later happen became inevitable.

I heard movement behind me. On cue, the goateed kid appeared at my shoulder. I did not see the gun until it was pointed, a dark hard glimmering thing, squarely at my temple.

The voice spoke again over the line. “I ask you one time. Where is she?”

Extracted from Dragonfish.

Vu Tran was born in Vietnam and raised in Oklahoma. He received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and his PhD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Practice in English and Creative Writing at the University of Chicago. His fiction has appeared in The O. Henry Prize Stories, The Best American Mystery Stories, the Southern Review, Harvard Review among other publications. Dragonfish, his first novel, is out now from No Exit Press.

Vu Tran was born in Vietnam and raised in Oklahoma. He received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and his PhD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Practice in English and Creative Writing at the University of Chicago. His fiction has appeared in The O. Henry Prize Stories, The Best American Mystery Stories, the Southern Review, Harvard Review among other publications. Dragonfish, his first novel, is out now from No Exit Press.

Read more.

Author portrait © Chris Kirzeder