We need to talk about nanny

by Karin SalvalaggioMy ex-husband and I moved from Berkeley, California to Kensington in 1994. I was the proverbial deer in headlights, having not a clue how the world functioned beyond the scope of my somewhat limited life experience. The word naïve doesn’t really cut it, as I was too naïve to notice my own naïvety. In truth, I’d basically arrived straight from a shopping mall, Valley Girl accent and all. I’m embarrassed even to think about it now.

One of the first things I noticed was that British mothers were surprisingly young. There were legions of them pushing prams along the expensive pavements of West London. Their children crowded the playgrounds and the parks. It was baffling. London was a world-class city. The women in Kensington were for the most part wealthy and well-educated, ambitious both culturally and financially. I couldn’t understand why so many of them decided to have children at such a tender age. It turned out that I was very much mistaken. Those young women pushing the prams and watching over children in playgrounds weren’t mothers. They were nannies and au pairs. Professional childminders were completely alien to someone with my background. My only points of reference were Mary Poppins and Mrs Doubtfire. Not much to go on.

I insisted I’d never have a nanny from the outset. Handing over my child to be raised by a stranger being too foreign a prospect. I knew very little about raising the two children I eventually had, but I knew even less about hiring and keeping staff. This resistance eroded with time. I wanted to work and there were few options available when it came to childcare. Besides, I was married to an investment banker and living in a rarefied world. Even their most zealously unemployed wives weren’t actually expected to stay home and look after their children. All our friends and acquaintances had nannies, au pairs and that rarest of luxuries, night nurses, who’d whisk the baby away from dusk to dawn so new mothers could sleep. And they say money can’t buy happiness. I was working as a freelance graphic designer. A nanny was required so one was hired. I never did get the hang of it.

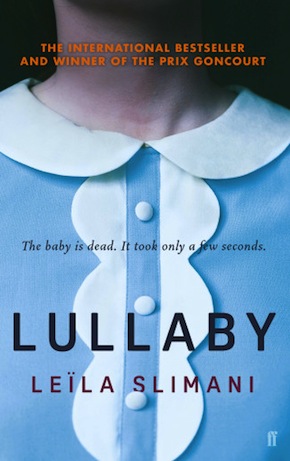

Leïla Slimani’s internationally bestselling novel is a tragedy that reads like a thriller.”

It wasn’t an easy relationship to manage. A stranger was living in MY home and caring for MY children. As far as I was concerned, they were the ones having fun while I laboured, isolated in my office on the top floor. We’d since moved to Chiswick, where we could afford a larger home. I’d work long hours making enough to cover the costs of the nanny and the occasional family holiday while my husband worked even longer hours making enough to pay for everything else a hundred times over. I loved my work for what it was worth, which was “icing on the cake” according to my ex. That little something extra. I didn’t realise it until later, but it was one of the many ways my contribution to the family was undervalued. I didn’t particularly like the women we hired to look after our children. Don’t get me wrong, they were well qualified and never to my knowledge put the kids in danger, but they weren’t family and they certainly weren’t friends. Yet it was one of the most intimate relationships I’ve ever had. They knew everything about me and I knew almost nothing about them.

It wasn’t an easy relationship to manage. A stranger was living in MY home and caring for MY children. As far as I was concerned, they were the ones having fun while I laboured, isolated in my office on the top floor. We’d since moved to Chiswick, where we could afford a larger home. I’d work long hours making enough to cover the costs of the nanny and the occasional family holiday while my husband worked even longer hours making enough to pay for everything else a hundred times over. I loved my work for what it was worth, which was “icing on the cake” according to my ex. That little something extra. I didn’t realise it until later, but it was one of the many ways my contribution to the family was undervalued. I didn’t particularly like the women we hired to look after our children. Don’t get me wrong, they were well qualified and never to my knowledge put the kids in danger, but they weren’t family and they certainly weren’t friends. Yet it was one of the most intimate relationships I’ve ever had. They knew everything about me and I knew almost nothing about them.

Leïla Slimani’s internationally bestselling novel Lullaby is a tragedy that reads like a thriller. The nanny dispatches the children in the opening sentences. The fact that the book remains a compelling read is down to the question asked in that first chapter. We are not looking for the who, we’re looking for the why. Slimani wanted to avoid cliché. She didn’t want to write a book about a “scary Mary Poppins” as “craziness is much more subtle”. The nanny hides her insanity well. Everything is internal. We rarely hear her voice. Slimani wanted to build an atmosphere detail by detail, leaving the reader guessing from one scene to the next, thereby putting them in the same position as the parents: “‘What’s happening? I think she’s crazy’, but the next page he’s like, ‘Oh no, actually she’s the perfect nanny.’” The writing is austere and almost devoid of dialogue. The detachment is deliberate. This is a forensic examination of the relationship between the mother and the nanny hired to look after her children. While the husband also plays a part, it is Myriam and Louise’s relationship that is at the centre of the story.

Lullaby opens with the mother’s grim discovery of one child that is most certainly dead and the other that will soon follow. The nanny has failed to do a good enough job dispatching herself and will live. There is blood and grief and detail, but little emotion in the account. Clinical detachment doesn’t lessen the impact. It is an effective, brutal examination of a murder. There is a great deal a writer can learn by looking at the structure and language Slimani employed. She found inspiration in books by Albert Camus and Marguerite Duras – “I wanted the book to be very clear and the style to be very pure… when you’re writing about ambiguity, trying to build an atmosphere of confusion, your writing has to be very clear if you want the reader to feel the confusion. It can’t be literal confusion; he has to understand exactly what you mean.”

Statistically speaking, we are much more likely to die at the hand of a loved one than a stranger. The hired carer is a less likely villain. As a child you are much more likely to be killed by a parent.”

The difficult scene out of the way, Silmani goes back to where it all started. Myriam, once a brilliant law student full of promise, has thrown herself into being a full-time mother, completely unaware of just how difficult it will be. We see her slide into despondency as she becomes isolated. She loves her children, but an important part of her identity is dying. In the end, she chooses to go back to work. Not one to shirk her responsibilities lightly, she puts all the structures in place to make sure her children are well cared for. Louise, the nanny they hire, is a 40-year-old French woman with impeccable references and a wealth of experience. Myriam and her husband are conscientious, caring parents. No blame should be laid at their door, yet they are seen as culpable. The parents describe the sensation of meeting Louise for the first time as a bit like falling in love. This should have made them suspicious. Statistically speaking, we are much more likely to die at the hand of a loved one than a stranger. (The statistics are damning. The hired carer is in fact a less likely villain. As a child you are much more likely to be killed by a parent, either through neglect or abuse.)

I had no trouble relating to Myriam, the mother of the two murdered children. I understood the elation she felt when she finally left the house unencumbered and able to engage her intellect, confident that she’d left her children in the best possible care. I understood how crestfallen she felt when she was undermined by Louise’s pathological zeal for perfection. Myriam soon became redundant in her own home. She could no longer look after the children’s dinner and bath time without Louise’s constant oversight. She couldn’t play, cook or clean as well as the nanny. She couldn’t tolerate the boredom that is part of the reality of motherhood, and she felt guilty for failing to embrace all aspects of the role. I understood how Myriam’s initial euphoria at Louise’s employment soured with time. I saw the same signs that Myriam saw, and just like her I scolded myself for being irrational. Like Myriam I tried harder to make the relationship work for the sake of my children and my career. I didn’t want to give up being a graphic designer any more than Myriam want to give up being a lawyer. We persevered. Thankfully, life isn’t usually as dramatic as fiction. Myriam’s children may have died but my children survived and thrived. It is therefore interesting that so many readers and reviewers have a strong aversion to Myriam. People I know admit they disliked her character immensely. It was her choice to go back to work. Her selfishness is viewed as monstrous yet the father shares none of the blame.

A woman in China has been sentenced to death for the murder of three members of a family who employed her as a nanny. She’d set fire to their apartment with every intention of putting it out before it spread, but like so many things in life, fire can be unpredictable. She had gambling debts that needed paying off and had hoped the grateful family would give her a cash reward for her heroism. While we can imagine her desperation as things spun out of control, it’s difficult to make sense of the thought process that brought her to the point of no return.

A woman in China has been sentenced to death for the murder of three members of a family who employed her as a nanny. She’d set fire to their apartment with every intention of putting it out before it spread, but like so many things in life, fire can be unpredictable. She had gambling debts that needed paying off and had hoped the grateful family would give her a cash reward for her heroism. While we can imagine her desperation as things spun out of control, it’s difficult to make sense of the thought process that brought her to the point of no return.

Closer to home, but no less inscrutable, is a murder case that has only just come to trial in New York after a five-year wait. A nanny named Yoselyn Ortega stands accused of murdering two children in her care before attempting suicide. The mother came home with her surviving child to find her other two children and the nanny in the bathroom. The children were dead, but the nanny was very much alive, having failed to dispatch herself with a knife to the throat. By all accounts, the parents are wonderful, caring people with the means and the will to insure their children’s safety. No one could have predicted something like this.

It’s been twenty years since the Louise Woodward trial made headlines. The boy that died in her care was a victim of ‘shaken baby syndrome’. After being sentenced to life the au pair was given a significantly reduced jail term in the appeal trial. She has since returned to Britain and seems to be living a fairly normal, albeit harassed existence. Notoriety of that calibre never lets you live in peace. Again, we are left somewhat in the dark as to why this woman lost her composure on that particular day and at that particular time. The family weren’t happy with her performance, but had no reason to believe their children were in danger. It is important to point out that in Louise Woodward’s trial, the defence attorney implied that the mother was to blame for the death of her child. As reported in the Irish Times, he repeatedly asked if her life was “busy”, if she failed to ring home the day her son died because she was “too busy”, if she found balancing work and motherhood “stressful”. This sentiment is strangely mirrored in some of the reviews Lullaby has received. Twenty years on and blaming the mother is still the easiest option. It isn’t a coincidence that the nanny in Leïla Slimani’s novel takes her given name from Louise Woodward.

I think every woman should fight for the right to be selfish sometimes… having a place for ourselves where we are not wives, not mothers, not workers, but just ourselves.”

From the outside it’s easy to judge these families harshly. The backlash then and now is sadly predictable. Mothers who work have made a conscious decision to leave their children in the care of others. Surely there is some blame to be laid at their doorstep. This is an outdated and overtly misogynistic line of reasoning. Mothers have just as much right to work as fathers. Full stop. But as mothers enter the workforce in increasing numbers, families will have to trust people and institutions outside the home to provide childcare. Extended family members aren’t always available and are potentially worse than hired help. Full-time motherhood and work in childcare, whether it be as a teacher or a nanny, have long been undervalued and often unsupported options. Conversely, women who pursue a career have been too often viewed with derision for leaving their children to be raised by others. It’s time we valued both equally. Mothers, childminders, au pairs, teachers and nannies play an incredibly important role in our society. They work incredibly hard and need support, training and fair compensation. Mothers who choose to go to work need access to well-funded quality childcare and public schools, so they are better able to work outside the home confident that their children are safe. In a world striving for equality in the workplace and the home these steps are crucial.

Slimani is very clear on her views: “It’s a sort of taboo to say this, but I think every woman should fight for the right to be selfish sometimes. I think it’s very important to fight for the right of having privacy, having a place for ourselves where we are not wives, not mothers, not workers, but just ourselves.”

I enjoyed Lullaby but struggled with it on a personal level. Each line struck a nerve. If I were one to fuss about such things as ‘trigger warnings’, I would have demanded one be put on the back cover. It brought up so many unresolved issues that I often felt raw, weepy and exhausted after reading a few chapters. But I still read Lullaby a second time. It was that good. Slimani goes beyond what news stories and tearful testimonies of grieving parents can tell us. We finally see this strangely intimate family dynamic through the nanny’s eyes. We watch her infiltrate the heart of family with stunning precision. For Louise is precise. Her perfectionism is pathological. She deploys it to win favour with her employers. She deploys it because she is a proud woman. It gives her a sense of control in her otherwise chaotic life. It pays her mounting debts. This job is both her life and her lifeline. She is the tightly wound coil at the heart of a family, holding on tight to a life she is destined to lose. She may love the two children in her care fiercely, but they will soon outgrow her necessity. Louise will eventually be forced to move on to another family as she’s done too many times in the past. How does it feel being the disposable heart of a family? What do years of living within reach of everything you’ve ever wanted for yourself, only to lose it over and over again, do to a person’s soul?

Lullaby leaves many questions regarding Louise’s motivations unanswered, which may frustrate some readers, but that was never really the point. If real life doesn’t have to make sense, novels which portray our experiences accurately won’t necessarily make sense either. This is a book that cuts a harsh slice out of the heart of a modern family to reveal what’s inside, consequences be damned. Slimani believes that “literature is not a trial, a novel is not a trial, you’re not reading a book to judge people. It’s the exact opposite… it’s another reality where you try not to put people in little boxes… It’s a special space, a special time, literature, where you can try to understand monsters.”

Leïla Slimani is a journalist and commentator on women’s and human rights, and was made Emmanuel Macron’s Francophone affairs minister in November 2017. Her first novel The Ogre’s Garden – forthcoming from Faber in 2019 – won Morocco’s Prix La Mamounia in 2015 and her second, Chanson douce, now published as Lullaby, won the Prix Goncourt in 2016. She is also the author of Sex and Lies, a non-fiction book about the sexual desires of Moroccan women, which became a literary sensation in France upon publication. Lullaby, translated by Sam Taylor, is published by Faber & Faber.

Leïla Slimani is a journalist and commentator on women’s and human rights, and was made Emmanuel Macron’s Francophone affairs minister in November 2017. Her first novel The Ogre’s Garden – forthcoming from Faber in 2019 – won Morocco’s Prix La Mamounia in 2015 and her second, Chanson douce, now published as Lullaby, won the Prix Goncourt in 2016. She is also the author of Sex and Lies, a non-fiction book about the sexual desires of Moroccan women, which became a literary sensation in France upon publication. Lullaby, translated by Sam Taylor, is published by Faber & Faber.

Read more

Read the opening chapter of Lullaby

Author portrait © Catherine Hélie/Editions Gallimard

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley mystery novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. She recently completed a new standalone thriller set in West London.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala

Quotes from Leïla Slimani were recorded by Bookanista at an event at Waterstone’s Gower Street.