The Book of Derek Parfit

by Mika Provata-Carlone

Walk around Oxford on any reasonably warm and relatively sunny day and, as you inevitably reach the Radcliffe Camera, you will invariably witness a perennial phenomenon: along a high, practically unclimbable and unassailable, Headington-stone-yellow and castle-worthy wall, there will be an impressive line-up of young people sitting down restfully, or leaning languidly against that Corallian limestone parapet, all basking in, and literally saturating themselves with the rays of sunshine and any available, welcome heat, original and reflected.

Places are hard to come by along this dazzlingly luminous sidewalk gallery, and once secured they are ferociously, if soundlessly, defended. The students read, chat, chuckle, think, they simply “sit and stare”; above all they perhaps absorb some of the ineffable and transcendental, arcane and mystical, material substance of that yellow wall, for it belongs to none other than All Souls College.

All Souls is for some a real monster, and for others a mythical beast. It is the ultimate, quintessential and true Ivory Tower, where only postgraduate members are allowed. It is a world of pure intellection, companionship of the mind, no formal teaching obligations (or sort of), and the battleground for some of the most legendary and notorious epic battles of distinguished ratiocination. A special set of exams predetermines admittance, on only seven subjects: Classics, Economics, English, History, Law, Philosophy and Politics. Questions posed in those exams have assumed near cabalistic status – although university graduates from Continental Europe may recognise them as plain vanilla, standard-issue exam fare, and as painfully or liberatingly familiar. Some delectable ones are “Have we seen the end of the ‘end of ideology’ ideology?” “Which concept is more fundamental, shape or colour?” “Are there any unanswerable questions?” or the simply irresistible “What gives Beckett hope?” The latter, given as it is here out of a more specific context, could open up the floodgates for a philosophy of the sublime dignity of despair, and the vital humanity of all existential crises (Samuel B.); or, dropping a ‘t’, for a theosophy arising from the life-giving sacred ethics of a faith based in the hope offered by Christ (Thomas B.), with some radical politics added in each case for good measure.

Dramatic irony aside, All Souls is a place of real beauty and substance: a world which, ideally, still venerates the sharing of our merely human understanding about the world, about ourselves, about the societies we have built, live in now, would like to see our children and their children exist in in the future. It is a modern-day revival of a Platonic Garden academy, an Aristotelian Lyceum, and a Stoic, well, Stoa, with a few Cynic pithoi scattered about the place, a firm rebuttal of any claims that ideas, thoughts, conversation and debate no longer matter. For All Souls, they are indispensable – they are what sustain all our souls, our very beings and worlds, what make us human.

As the College website makes proudly clear, “You get seven years of research in ideal conditions, in regular contact with leading scholars in your field, and free from many of the pressures, financial and otherwise, which can afflict graduate students. In seven years, you might, for example, be able to complete a doctorate, turn it into a book, and then get started on another project.”

Parfit was undeniably a man of extraordinary mental acuity, driven by an equally insatiable and formidable impetus to question, to ponder, and to seek to find a way into a certain (literally and concretely certain) wisdom of things.”

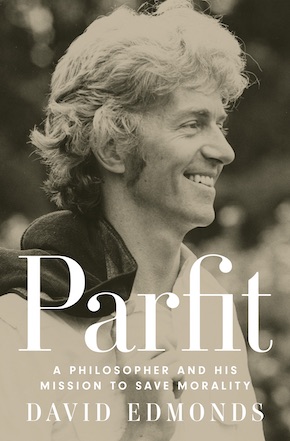

All Souls has, in this way, nurtured, sheltered and produced many extraordinary minds, a critical cohort of individuals for whom thinking, and the search for meaning and understanding, truly matters – and, above all, makes a difference. One of its most fabled members seems to be Derek Parfit, whose life and work form the basis and substance of David Edmonds’ new book, Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality. A philosopher’s philosopher for some (as we are told), Parfit was undeniably a man of extraordinary mental acuity, driven by an equally insatiable and formidable impetus to question, to ponder, and to seek to find a way into a certain (literally and concretely certain) wisdom of things. He quested for a way out of the Platonic Cave and into the bright, dazzling light, and upheld, as though an intrepid, new Er, the faith in Truth and Right. He nonetheless rejected Platonic and Christian belief in the afterlife as such and, somewhat convolutedly, he dismissed the possibility of attributing either acclaim or blame, and therefore either praise or punishment, by erecting a dizzyingly ratiocentric House of Cards argument as regards the notion of self-identity – or the continuity and oneness of our consciousness through life, time and experience. And yet he also believed, and fiercely, in the existence and permanence of first principles and values, in morality as a sempiternal category, in moral truth as an incontestable absolute.

For some Quixotically, for others valiantly and groundbreakingly, Parfit sought to reaffirm the notion of ethical reflection and action, of moral responsibility towards each moment, even towards what has not yet happened or come into existence. Equally central is Parfit’s paradigm of Climbing the Mountain as a way of showing that full perception of the Truth, philosophical or otherwise, is possible only if multiple human attempts at understanding are put together – just like perceiving a mountain in its totality is only possible if one climbs it from multiple sides. One would necessarily arrive at the same summit with a more complete understanding of the whole. It was his way of arguing that if any theory is right, then it must complement and ultimately agree with any other theory that claims to be right. The biblical precedent here is resounding and multiple, from the closeness to God and a divine truth of Mount Ararat and Mount Sinai, to the “divine through the human” of the Mount of Olives and Mount Zion, to the evincing of the reality of God on Mount Carmel and Mount Tabor.

Parfit has been hailed as a pioneer of contemporary social ethics and engagement, or, as Edmonds puts it, as the philosopher whose mission was to save morality. It is a proclamation that is both reassuring, if one thinks of our nearly dehumanised post-modernity, as well as warranting a certain amount of sceptical readjustment or refocusing, if one has memory enough and sufficient cultural sincerity to acknowledge that everything Parfit ever proposed or argued for, each principle he so agonised to redeem and to reveal, had already been upheld, or even put into practice before – whether by writers (Samuel Beckett being a case in point), and past fellow-philosophers or, perhaps more poignantly and organically, by the several millennia of a Helleno-Judeo-Christian tradition of life and thought. A tradition Parfit grew up with, was immersed in, reflected and debated through.

Parfit’s life and thought are the stuff of dreams and nightmares, or so it would seem. Apocryphal stories abound and multiply about this man who appears to have been at one and the same time the most endearing and the most infuriating bundle of paradoxes, contradictions and tug-of-war states of being and mind.

Parfit was born in China in 1942, amid many divergent and interconnected wars, in a world of flux at every level, of dissolution, conflict, transformation, catastrophe and reconstruction (or even perhaps of hoped-for resurrection, as his parents were medical missionaries). His childhood is one of movement, multiculturalism, polymorphism, inter-perspectivism, fervour and doubt, and a certain cross-eyedness. It is also a maelstrom of not always reconcilable emotions and life directions.

His parents were attracted opposites, whose relationship, Edmonds upholds, had a deeply formative impact on Parfit’s life and way of thinking. Norman Parfit, the son of an Anglican clergyman, was a doctor of preventive medicine and later a public health policy official; he was disenchanted by missionary Christianity, tempted by Maoism, devastated by the possibility of a meaningless nihilism or materialism, and susceptible to bouts of depression throughout his life. Jessie Parfit, the daughter of Christian missionaries in India, was a medical doctor who would become a leading researcher in the importance of family structures and home-life welfare, and an expert in child psychology and child development, specialising in emotionally disturbed children. Her daughter Theodora Ooms, Parfit’s elder sister, would also become a therapist, researcher and consultant, focusing on family, marriage and relationships.

Edmonds deems that the atmosphere was oppressive, forbidding, alienating; yet Parfit himself refers consistently and unequivocally to his close bond with his parents, to the vital importance that his many weekly meetings with them had for him. He remained very close to both his sisters and their families throughout his life, and this closeness would result in what was perhaps one of the most excruciating and perplexingly problematic experiences of his life, following the death of his younger sister in a car accident. He dedicated his first book to this immediate, immutable close-knit familial world, his parents and his two sisters, and what is perhaps nearer to some, or part, of the truth, is that Parfit grew up with a particular understanding of the need for and the significance of personal attachments, as well as with a recognition of human complexity, fallibility and fragility. If one chooses that line of vision, much of his philosophy and idiosyncrasies perhaps make very different sense.

What we know about Parfit growing up is that he had easy brilliance, inexhaustible curiosity, a true lust for life and learning, the quirkiest and most irresistible sense of humour and social presence.”

What is doubtlessly true is that Parfit grew up in what must have been a truly formidable intellectual environment, which somehow brought together a poetical, bookwormy, idealistic vision, with a more ratiocentric conviction in the findoutable and pindownable nature of things. Something of a pulsating and thriving combination of the Tinman and the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, perhaps, with Toto prancing about, and the hovering shadiness of Oscar Zoroaster Phadrig Isaac Norman Henkle Emmannuel Ambroise Diggs conjuring up all sorts of Goyaesque monsters produced by reason. What we know about Parfit growing up is that he had easy brilliance, inexhaustible curiosity, a true lust for life and learning, the quirkiest and most irresistible sense of humour and social presence. He goes from one exceptional school to the next, all private, all places both of distinction but also of very real inspiration and aspiration. His is a rather special missionary family, with generously wealthy connections, happily tangible material tastes, and a strong sense of what truly matters – and that was only what was good, in every sense.

When his parents lost, while in China, the formal understanding of a religious faith, what remained unshakable was the firm belief in a transcendental sense of the Good as a first principle and as an immanent value, as it would for Parfit. His last school, Eton, was a crucial transformative experience, and anecdotal stories, and the recollections of those who were linked to Parfit in indissoluble friendship well beyond those years, speak of a sprite-like kind of genius as well as of a pervasive, mystifying oddity. Oxford would be the next step and stage, and from there, the real meandering genealogy and annalistic history of the development and multiple reformulations of Parfit’s mind and existential outlook truly begin. Parfit would remain umbilically connected to Oxford, in one way or another, until the day he died.

Oxford as a place of insularity and isolation, and perhaps of a certain elitism and intellectual preciousness, but above all as an almost holy congregation of brilliance, is at the heart of David Edmonds’ attempt to produce a definitive vita of Parfit the man and Parfit the thinker. The sheer meticulousness and wealth of the biographical details guarantee a vital pulse that runs unwavering throughout Edmonds’ narrative, and the catchy captions of his “stages on life’s way” ensure an impressionistic structure for what might otherwise loom as a very “loose, baggy monster”. “I wanted the book to be accessible to civilians, a.k.a. non-philosophers,” Edmonds makes clear in the introduction, and if one can overlook the ambiguous use of ‘civilians’ in the sentence (are philosophers to be understood as a military hegemony?), such a declaration holds genuine promise.

Edmonds’ book (similar to Parfit’s life, one might argue) is rich and dense; it is especially permeated by a sense of a rip current cutting across the seeming linearity of the chronology and the more academic analysis. Parfit is a tremendous fabric of stories, memories, references, personal testimonies, research material and original quotations, and it is an equally, tremendously, heartfelt invitation to feel and engage with the rhythm and presence of a life. It is absorbing, fascinating, replete with occasions for pause and reflection, full of echoes of lives past, lives lived, lives almost obsessively examined. The unignorable flipside, however, is an authorial voice which claims incontestable omniscience throughout, an irrefutable authority of selection, focalisation and interpretation, and near-axiomatic totality of vision. Tantalisingly, this comes with an unremitting Janus-facedness of positions: Edmonds both venerates Parfit, and almost kicks him off his pedestal every chance he gets.

It is a duality that many might quite readily apply to Parfit himself: was he a snob and an aristocrat, or a bona fide member of a nebulously defined common people? Was he ordinary or extraordinary? Was he a compulsive recluse, or just enamoured by the life of the mind? Troubled and troubling, or earnest and almost primordially passionate? An abstractionist or a practical, life-saving moralist? An all-out atheist, or a crestfallen Anglican, desperately and passionately holding on to an ineffable spiritual side to mere mortality? Was he kind or an egotist? An altruist or a closet self-serving capitalist? Rude or just unaware of social inflexions, complexities, conventions? Was his world a communal one, or a solipsistic bubble, a Derek-centric universe, or a ‘Derekarnia’, as someone called it? Most importantly, was he a sage or a pedlar of counterfeit philosophical goods? Did he rescue morality (and philosophy) from oblivion, or was he their scourge, as Simon Blackburn scathingly argued in the FT in his review of Parfit’s monumental, yet in Blackburn’s view insubstantial and inconsequential On What Matters?

Edmonds himself is in principle a staunch advocate of the positives rather than the negatives featured on this (only partial) list of the discordant reactions to Parfit’s personality, philosophical output and significance over the years. Through close scrutiny of Parfit’s biographical details, a focused, selective reading of his writings, the forensic pursuit of chronological linearity and sequentiality, and a psychotherapeutic inspection and analysis of motivations, emotional responses and processes and personality development, Parfit seeks to evoke the presence of the living man, and quite determinedly to convince us of the brilliance and incontestability of his positions and propositions. The cardinality of his contribution to the common Nous.

Somehow, however, the portrait of Parfit that emerges is often of a split personality or of multiple, superimposed and over-exposed Polaroid photographs. It can feel ambivalently positioned between the exceptional and the pedestrian, creating an impression of Parfit as both a self-assured, audacious mediocrity and an oblate-like, solitary genius. In this gallery of mirrors, some reflections are of an innocently moral man, aspiring to an almost saintly degree of benevolence, while evincing near-callous arrogance and presumption or flippant disingenuousness. Parfit appears uniquely sensitive to injustice of all sorts, yet presents as being eminently comfortable in assuming as a personal prerogative any number of special favours and graces, opportunities and possibilities. He is shown to us as unfailingly generous and charismatic and as an unblushingly bombastic fraud; as a social and political, liberal Aristotelian animal, and a Savonarola-like mystic with totalitarian predilections.

The evidence, both biographical and textual, supports this Parfitean “I contain multitudes” perspective. What might perplex readers is the tone of mordant irony that seems to accompany at times the complex portrayal. Edmonds makes a concerted effort to present, alongside the life, the substance of Parfit’s mind. This is a colossal task, which Edmonds undertakes with relish, confidence and bravura. Parfit’s writings have been compared to those of Wittgenstein, both by way of compliment and not quite so. They each time start off mellifluously, eloquently, conversationally, matter-of-factly, before they escalate into an array of parsed assumptions and intricately woven syllogisms which often appear as a magisterial mind chart (or Warburgian Mnemosyne map) of Very Important Thoughts, rather than as reasoned interconnected positions and structured arguments. The cynical view, and one taken by several of his critics, is that he lacked the discipline to provide the originality of his ideas with meaningful form; Parfit never trained as a philosopher, at least in strict academic terms. His Oxford degree was in history, and philosophy emerged as a path while on a postgraduate open fellowship in America. For many, this accounts for his ability to look at things from purportedly unorthodox perspectives, and for his disregard for a rote application of methods and received practices. Idealists and romantics would say that his sheer passion for the miraculousness of the human mind is what makes him so extraordinary.

As Edmonds states, quoting Saul Smilansky, Parfit is deemed ‘the most original moral philosopher since Kant’ – but what about the giants on whose shoulders Kant himself (so precariously for many) stood?”

A more sober view is that the Icarus path he chose to take rendered him also unaware of the material failings of many of his philosophical pairs of wings. It also allowed for a presumption that the past 2,000 or so years of human contemplation mattered little or not at all. As Edmonds states, quoting Saul Smilansky, Parfit is deemed “the most original moral philosopher since Kant” – but what about the giants on whose shoulders Kant himself (so precariously for many) stood? From that position, many of Parfit’s and Edmonds’ assertions lack solid ground, especially as regards their claim to an absolute originality. Thomas Nagel’s argument, for example, on the “view from nowhere”, which Edmonds uses for Parfit, namely that “we can, as it were, look down upon ourselves, judge ourselves, assess ourselves, as though from outside our skins. We have a view from nowhere,” is quintessentially Aristotelian, and forms the basis of Aristotle’s Poetics. Ecstasis was his term for standing outside ourselves (ek-stasis) in order to share the experience of another, enter into their consciousness through simple human compassion, and use the dramatisation of another life in order to examine our own. This was the miracle and very ordinary reality of Athenian dramaturgy. In the same period as Nagel’s book, there is a new wave of psychoanalytic boom, which familiarised terms such as abstraction and sublimation, and which essentially function in the same way as the Aristotelian ecstasis in their ideal form. Not to mention T.H. White’s The Book of Merlin as regards experiencing what Nagel again calls the “What is it like to be a bat?” principle. Similar blind spots of Parfit’s (and occasionally Edmonds’) microfocus are strewn throughout the book, most dramatically perhaps in the case of Frances Kamm.

Edmonds has sought to contextualise Parfit’s intellectual brilliance or genial eccentricity in using casuistic reasoning, even to the point of apparent absurdity, by referring to other fellow philosophers who also resort to what ancient Greek philosophy classed as ‘paradoxes’. Frances Kamm famously created moral thought experiments based on what is called the ‘trolley problem’, involving extreme moral choices on what lives should be saved, and which should be sacrificed for a perceived greater good. What Edmonds might have added in her case is the context of her impossible ethical dilemmas. Rather than being solipsistic bravura displays of cerebral agility, Kamm’s paradigms derive from and reflect real historical tragedies and questions, more specifically the harrowing debate on whether the Allies should have bombed the German concentration camps, a debate triggered by Jan Karski’s 1942 report. Opening up the perspective in this way would have aided to reposition philosophy as a passionate effort to arrive at an understanding of things, or at a way of exploring such an understanding, rather than being an exercise in casuistry and Pantagruelist education…

Another example of the occasional, significant blind spots in Parfit involves Edmonds himself and no other than Hitler. “The Non-Identity Problem has other implications for many debates. Although Parfit applies it to the future, one can also see how it might discombobulate attitudes to the past. Adolf Hitler made the lives of scores of millions of people much worse – but not the life of this author. This author (a child of refugees) certainly owes his existence to Adolf Hitler [since his parents met and married in their country of exile, England]. Given Hitler’s disruptive impact on the world, the same is probably true for most readers. Should I regret this monster’s ascent to power and the destruction he wrought,” given the benefit Edmonds claims it had for him? The seeming (provocative and shocking) brilliance of this postulate only subsists while the smokescreen of rhetoric is there, however, and Edmonds does not seem to be aware of the chasmic lacunae in this pronouncement, or in other similar analyses and elaborations. The first obvious non sequitur is that the author was not born as a direct result of Hitler’s actions. There is no basis on which he can argue that his parents might not have met had Hitler not existed or acted the way he did. The claim also suffers on further, eschatological rather than pragmatic grounds: the last sentence quoted is a travesty of scholastic, ratiocentric attempts to explain away the existence of good and evil, death and pain, while still maintaining a belief in God. It is arguably the most platitudinous argument of atheists: if God is there, why is there evil, devastation and suffering? The scholastic argument goes that it is all part of a divine plan beyond human ken and control, and far larger than our individual selves. Almost perversely (for there seems to be no irony in the passage), Edmonds’ exemplification of the Non-Identity Problem seems to postulate a substitution of the divine plan by a humano-centric one, in this particular case, Edmonds’ birth.

The question of God and the presence of Evil is a key concern for both Parfit and Edmonds: “The main reason [Parfit] couldn’t believe in God – at least in the Christian God – was the problem of Evil. An all-powerful, all-benevolent God would surely have arranged the world so that it contained no suffering.” One wonders whether this implies that in other religions God is perceived as not all-powerful or all-benevolent, and that this somehow accounts for what is designated here as Evil? More fundamentally, the key obfuscation is the term Evil itself. Should not a distinction be made between Evil as a force and agency in and of itself, in which case it contradicts the singularity of God, and Catastrophe, a factor of existence with no moral agency or anthropomorphic moral attributions? Free will comes into play in such a case, since evil in human life is the result of chosen human action. Catastrophe is a more complex notion, which presupposes an understanding of ourselves as part of, rather than auctors and masters of creation itself.

Chapter 13, ‘The Mind’s Eye in Mist and Snow’, on Parfit and photography, is perhaps the most eloquent in the book. It reveals Parfit’s almost Byronic idealism, his unsettled, unsettling quest for a perfect order, his frequent total disregard for actual facts and real conditions (he notoriously tweaked or changed stories, invented quotations, plagiarised sources, or cheated at cards). His photographs are as stunningly beautiful as they are supremely controlled, doctored and manipulated, artificially (or falsely) perfect and sublime –an iconic reflection, one could argue, of his philosophy and personality. Frances Kamm is quoted as saying that “It seems to me that [Parfit’s] highly impartialist view of ethics might seem to some as another way to get rid of people,” and this is just what Parfit would do in his photographs: he would remove any elements that in his view marred the particular version of perfection he had in mind, he would move buildings around, to fit an equally personal perception of aesthetic absolute. There is very little human presence, if any.

Edmonds argues that “there are two possible interpretations” for Parfit’s photographic manipulations. “Either he was trying to improve on reality, or he thought that by ridding the image of eyesores he was laying bare the beauty of reality. The latter explanation is supported by one of his photographic rules: while willing to erase parts of an image, he would never add to an image – he would never photoshop anything in, only out.” In fact, as Edmonds goes on to show, he broke the non-addition rule on several occasions. Parfit himself would say that “I don’t want to destroy the sense that we are looking at the buildings themselves, not a representation of them. I don’t invent anything, since every part of every image was taken from somewhere in the original image.” It is an extraordinary statement of the truth Parfit saw in the art and practice of the trompe l’oeil, in what is essentially the construct, what fools the eye, and the make-believe. His definition of his photographic methodology is clearly not articulated in the context of aesthetic value, or of artistic truth.

Parfit also controlled visuality by determining the conditions of light and shadow, clarity and the optics of distortion. He never took photographs when the sun was at midpoint, insisting instead on what he called “the near-horizontal golden rays at the two ends of the day” and on the mysteriousness of fog or the drama of snow. He always photographed, it seems, specific places in each city. Edmonds notes significantly that Parfit was only interested in, and comfortable with, looking at things through a frame, whether that was the frame of a picture, a window, an arch or door, the camera viewer or a screen. A real or conceptual frame enhances the sense of a need to prescribe, control, select the focus and delimit the view (philosophical) and the vision (optical). For Edmonds, any “links between the substance of Parfit’s philosophy and his photography… were quite tenuous,” while noting the need in both cases to “impose reason and order on morality, to iron out wrinkles” – a view shared by Janet Radcliffe Richards, Parfit’s life companion and wife. Nonetheless, all the books published by Parfit (Reasons and Persons and On What Matters, as well as the counter-volume Does Anything Really Matter? edited by Peter Singer), are predicated explicitly and from the outset by Parfit’s photographs on their covers.

For Appleyard, it is impossible to look at the photographs without feeling obstructed or confronted by, immersed in the philosophy they somehow, yet indisputably engage with and address.”

Was there something else to photography than a creative, aesthetic impulse? Parfit was a ruthlessly selective editor when it came to his photographs (unlike the case with his philosophical notes, perhaps). The images he did keep were precisely edited and definitive, and, as dust jackets, certainly an extension of the words, concepts and logical formulations he used to express his thoughts about the world. Yet one may sense that there was much more. In 2018, a year after his death, Owen Laub and Sam Sokolsky-Tifft, two of Parfit’s last student cohort, came up with the idea of a public exhibition of his art as a photographer. It took place at the Narrative Projects Gallery, in London, curated by Sokolsky-Tifft and Olivier Berggruen. It was called Derek Parfit: The Mind’s Eye, with a catalogue and essay in German, Derek Parfit, Das Auge des Geistes (2018). The German title allows for that ‘something else’ which the English translation withholds, and which many of Parfit’s readers and critics perhaps overlook: the Eye of the Spirit, and his sense of spirituality, his search for meaning and even sacredness beyond mere pragmatism and materiality. Sets of five reproductions of Parfit’s exhibited photographs were on sale for £1,500 per set. This exhibition does not come up in Parfit, yet Olivier Berggruen’s and Sokolsky-Tifft’s essay is well worth reading:

“What is the relationship between these two seemingly unrelated activities, Parfit’s philosophy and his photography? What do his photos tell us about his philosophical work? And what did this philosopher see? […] Looking at the photographs one wonders: did Parfit capture these images with a philosopher’s eyes? If we accept the idea that art externalizes the inner world, for Parfit such a world involved language rather than images. Yet words have the ability to project images, as images have the ability to evoke words. The dust jackets of Parfit’s published works were the one hint that Parfit did something other than philosophy, something that could communicate in another form the concepts expressed in language in the book. […] One has only to look at the cover of Reasons and Persons to divine Nietzsche’s epigram on the first page: ‘At last the horizon appears free to us again, even granted that it is not bright… the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an open sea.’”

Equally worth reading is the beautifully evocative essay by Jonathan Derbyshire written in April 2018 for the FT reviewing the Narrative Projects exhibition. This too seems to be missing from Edmonds’ Parfit: “Sokolsky-Tifft recalls Parfit quoting a line from Homer in the middle of a talk. ‘He started to weep because he found it so beautiful. That was when I first started to get the idea that this was a man with a strange heart, for whom art was always bubbling beneath the surface of these logical arguments.’” It was that heart, that movement of the soul, or the ineffable beyond the doubt, perhaps, that Parfit sought to find and capture through his lens. Responding to the interpretation that Parfit’s photographic ritualism may have its basis in his condition of aphantasia, Derbyshire again writes: “It wasn’t simply that he wanted a record of his favourite places to make up for some neurophysiological deficit – he was also trying in his photographs to capture their timeless essence.” Just as he tweaked his images to fit an ideal image, “he believed that the job of the philosopher is not to describe the beliefs we already have about morality but to change them when, as they often do, they turn out to be false. ‘By temperament,’ Parfit wrote in the introduction to his first book, ‘I am a revisionist.’ That was as true of his photography as it was of his philosophy.”

In June 2018, a third piece on the same exhibition, this time by Bryan Appleyard for the New Statesman, goes even further: its title is quite simply and explicitly ‘What Truth Looks Like’. Like Derbyshire, Appleyard too has strong points to make. One concerns Parfit’s life project as a whole: “Parfit was only a part-time photographer. His primary work was the pursuit of moral truth in a godless world – a Snark [after Lewis Carroll] that has, in the past, always turned out to be a Boojum.” For Appleyard, it is impossible to look at the photographs without feeling obstructed or confronted by, immersed in the philosophy they somehow, yet indisputably engage with and address. “The pictures are deeply inexpressive. Of course, these buildings, these bridges, these waterways are beautiful, but there is nothing personal about this beauty. Parfit was dearly going for something still, timeless, something beyond ourselves. […] The connection between the photographs and the work is flagrant. […] The whole becomes a work of art, a vision rather than a proof of meaning in a godless world. Parfit discovered something that wasn’t entirely a Boojum but it certainly wasn’t a Snark.”

As suggestively revealing are the photographic portraits of Parfit himself. The image that emerges, throughout the years, both in professional portraits and in snapshots from life, is of such an extraordinary visual expressiveness, of an awareness and use of the physical to complement the non-sayable or even the metaphysical.

What is one to make of Derek Parfit and of David Edmonds’ Parfit? In both cases, the most apt term is formidable, the substance and presence unignorable. One cannot fail to engage, to seek a dialecticity and an exchange, even where Corallian yellow walls may seemingly block the way. Parfit as a man and a thinker is an engrossing enigma and in both cases an occasion for very serious reflection. David Edmonds’ book equally offers vast grounds for both introspection and critical reciprocation, as well as proposing itself as an arguably bewildering canonisation of a larger-than-life philosopher and a very perplexing man. As one turns the final page of a life and a story, a quote from Wittgenstein comes also to mind:

“Here we come up against a remarkable and characteristic phenomenon in philosophical investigation: the difficulty – I might say – is not that of finding the solution, but rather that of recognising as the solution something that looks as if it were only a preliminary to it. ‘We have already said everything. – Not anything that follows from this, no, this itself is the solution!’ […] The difficulty here is: to stop.” (Wittgenstein, Zettel, para. 315)

Could this solution, concealed behind a rationalistic ‘preliminary’, be the shadow Parfit always lived with? Namely a sense of faith in a spiritual, sacred dimension of things?

—

David Edmonds is a philosopher and the author of many books including The Murder of Professor Schlick, Would You Kill the Fat Man? and (with John Eidinow) the international bestseller Wittgenstein’s Poker. He’s a Distinguished Research Fellow at Oxford University’s Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, an ad hoc columnist for the Jewish Chronicle and a former contributing editor to Prospect. With Nigel Warburton he produces the popular podcast series Philosophy Bites and is a regular presenter on BBC Analysis. Parfit is published by Princeton University Press.

Read more

davidedmonds.info

@DavidEdmonds100

@PrincetonUPress

Author photo by Nina Sologubenko

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/