The causes of a life: Mary Shelley in Bath

by Fiona Sampson

STRICTLY SPEAKING, OF COURSE, it wasn’t Mary Shelley who arrived in Bath on 10 September 1816, but Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. The nineteen-year-old who alighted in the city that Tuesday afternoon wasn’t yet the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, the up-and-coming poet and heir to a baronetcy. Instead, she was his unmarried partner, as well as the mother of his third surviving child.

This was at the time an almost unthinkably radical arrangement, not least in Bath. Jane Austen’s novels were at this very time examining the city’s fashionable marriage market with delicate glee. But when Mary sat down to her late lunch that September day, ‘free love’ had already been framed as a revolutionary challenge to traditional institutions – the Church, the monarchy, marriage – by radical political philosophers, in particular the parents whose names she carried. Her mother, who died as a result of giving birth to her, had been Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Wollstonecraft had married Mary’s father, William Godwin, only after learning from experience with her own first child how hard it was to live as an unmarried mother at the end of the eighteenth century. Godwin, whose many disciples included Percy Bysshe Shelley, had also argued, in Political Justice (1793), for free love. But, by the time his daughter arrived in Bath that afternoon in early autumn, he had cut her off because of her unmarried relationship.

All the same, as she searched for lodgings that evening and again the next day, Mary was not alone. With her were her nine-month-old, William, and his nursemaid Elise Duvillard. Little ‘Wilmouse’ was Mary’s adored second child; her first-born had survived only a few days. But also in the party was her stepsister, Claire Clairmont, and it was for her sake they were in Bath. A few months Mary’s junior and also unmarried, Claire was pregnant by Lord Byron; who was refusing to have anything to do with her. It was only a few months since the celebrated poet and peer, famously described by his former lover Lady Caroline Lamb as ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know,’ had been driven into exile by revelations in his divorce case. Claire’s pregnancy was forcing the stepsisters to retreat from the gossipy centre of things in London. Where however Mary’s own ‘sweet elf ’ Percy was free to come and go, returning from time to time to her in Bath.

The writer we celebrate as Mary Shelley, pioneering woman and author of the first science fiction novel, Frankenstein (1818), as well as the first dystopian fiction, The Last Man (1826), lived from 1797 to 1851. But in all her life, the four months she was to spend in Bath would prove among the most important. For now, though, she was simply being a responsible sibling in a family crisis.

Claire had been a spoke in the wheel ever since Mary ran off with Percy at sixteen. On that whirlwind trip to Europe in 1814 – not an elopement, since the poet was already married, but something between a huge adventure and a sort of grooming – Claire had, bizarrely, come too. It had since proved impossible to displace her, not just from the household but from Percy’s confidence. True, he had sent her away to Lynmouth in Devon for some eight months – conspicuously, long enough to have a baby. But she had since come roaring back into their lives and led them to the shores of Lake Geneva, where Byron was to spend the summer at Villa Diodati.

1816 would be remembered, however, as The Year Without a Summer. A huge volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora, in what was then the Dutch East Indies, had clouded earth’s atmosphere with volcanic dust, causing wintry conditions in midsummer. Across northern Europe, peasant subsistence farmers were starving; just three days earlier, Mary’s party had survived a rough Channel crossing on their way home from Geneva. Still, Claire had not lost her baby; and so here they were, marooned in Bath.

The accommodation Mary now found, at 5 Abbey Churchyard, was close to where they first arrived, in a district busy with the coaching inns so necessary for the resort’s prosperity. The rooms were right in the centre of the social action: next door to the famous Pump Room, where invalids and holidaying socialites congregated to take the waters, see and be seen. Appropriately enough, they were above ‘Meyler’s Circulating Library and Reading Rooms’. They also offered a glorious close-up of the Abbey’s West Front, where angels clamber up and down Jacob’s Ladder between heaven and earth: a proverb about aspiration and moral effort that could serve as a motto for Mary’s Frankenstein. It was the perfect address for people watching and, had Mary but known it, for ghost hunting too, since the as yet un-rediscovered Roman Baths lay right beneath her feet.

Twenty years earlier, the Italian scientific showman Luigi Galvani had appeared to demonstrate that biological life is electrical by publicly shocking the bodies of animals and executed criminals into motion.”

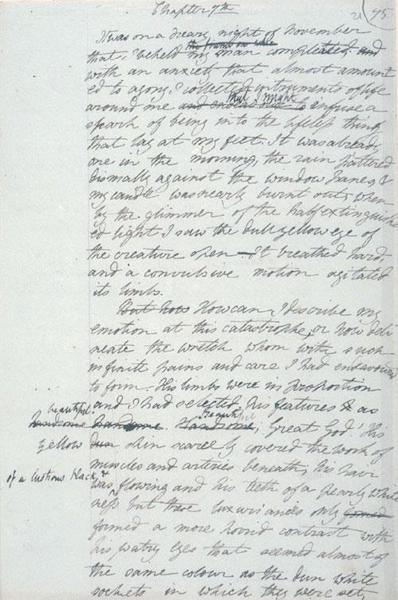

And indeed, once she had settled Claire elsewhere, at 12 New Bond Street, she set to work on a ghost story. She was writing in response to a challenge. Three months earlier, in Geneva, Byron, his doctor John William Polidori, and Percy Bysshe had relieved the unseasonal gloom by discussing what Mary’s Dr Frankenstein would call ‘the causes of life.’ Fresh-minted atheists, they wanted to reframe the Christian idea of a ‘divine spark.’ It was a fashionable topic. Experimental science, newly popular, was being disseminated by public lectures, including those Mary would attend at Bath’s precursor to its Royal Literary and Scientific Institution in Queen Square. Twenty years earlier, the Italian scientific showman Luigi Galvani had appeared to demonstrate that biological life is electrical by publicly shocking the bodies of animals and executed criminals into motion; this belief was now being modified but his work, known as Galvanism, remained at the forefront of such discussions, including in Byron’s salon.

A more recherché form of entertainment were German Schauer-roman, or shudder-stories, which went beyond stately British Gothick novels into necromancy and schlock. After the villa house party had read a collection of these, called Phantasmagoriana, Byron proposed they each write a ghost story. The game became something of a damp squib, like so much of that summer; both poets lost interest. But it sowed the seeds of both Polidori’s 1819 short story The Vampyre and what would become Mary’s second book.

At Abbey Churchyard, she started to devour fiction. For the previous couple of years, she had struggled through the classics to try and catch up with Percy’s Eton and Oxford education. Now, probably taking advantage of the lending library downstairs, she read across the still-evolving novel genre, from Gulliver’s Travels to Don Quixote, Richardson to Rousseau, and Walter Scott to Lady Caroline Lamb’s recently published roman à clef about Byron, Glenarvon. She and Percy even read Paradise Lost, from which she would take the epigraph to Frankenstein.

We know this was research, not sheer book-wormery, because – as the pragmatic publisher’s daughter she was – Mary would soon decide to enlarge her original ‘ghost story’ into a more saleable novel length, and cast around for a way to do so. Her triumphant formal solution was to nest three first person stories – the creature’s, Frankenstein’s and the Arctic explorer Captain Walton’s – inside each other, making us match them up to each other. Mary didn’t forget the science her fiction needed, either, whizzing through Humphrey Davy’s Introduction to Chemistry at the end of October. She also took up drawing, with lessons on Mondays and Thursdays: although the curious journal entry for 8 October records having a Tuesday lesson instead.

Two deaths and a wedding, in a life-changing tangle. However much of a love match the new Mrs Shelley had made, hers was also a marriage of convenience.”

Mary’s journal entries were clipped to the point of code. The mysterious ‘men dressed in black’ accosting Percy on 20 October, for example, were debt collectors. As the daughter of famous, even notorious parents, she knew how much the written record could make or break a reputation; she was already writing for posterity. So on 8 October, she recorded simply, ‘Letter from Fanny,’ and, on 9 October, ‘In the evening a very alarming letter comes from Fanny.’

But much is concealed here. 9 October was the very evening that Mary’s ‘other’ sister, her half-sister Fanny Imlay, killed herself in a Swansea hotel. Mary Wollstonecraft’s elder daughter had travelled alone – but dressed in her mother’s underwear – from London to the embarkation port for Ireland. She was following in the footsteps of a pair of maternal aunts who first offered her a Dublin teaching post, then withdrew it because of her younger sister’s sexual reputation.

‘Our’ Mary had a lot to feel responsible for, then. But why did she also use the journal to establish a (possibly false) alibi for 8 October; the day when Fanny had, as she told a fellow passenger, made an unnecessary coach change in Bath? Did Fanny – who had served as go-between for her sister and father, and may have been in love with Percy – come to see the couple, who were after all living so close by the town’s coaching inns? Was she rebuffed? Fanny was often overlooked by her family, who regarded her as plain because she had her father’s dark colouring. It’s hard not to hear the echo of her sadness in Frankenstein’s creature: ‘I am alone and miserable. Only someone as ugly as I am could love me.’

Either way, suicide had now been added to the family quota of social shame. Yet Mary noted only ‘…the worst account. A miserable day. Two letters from Papa. Buy mourning…’ Her letters were similarly rehearsed. On 5 December she wrote longingly to Percy, ‘Give me a garden & absentia Clariae.’ But neither the absence of Claire nor a garden were to come her way any time soon. Instead, on 15 December she recorded ‘news of the death of Harriet Shelley.’ Her lover’s wife had drowned herself in the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park. Just twenty-one and heavily pregnant, Harriet had, like Mary, run away at sixteen with Percy despite his reputation. When she was abandoned, her family refused to take her back, leaving her with no means of support. Percy would always maintain the child she was carrying that December was not his, though it’s hard for a modern reader to believe him. Willy-nilly, Mary wrote up the outcome with her habitual brevity. In London, ‘A marriage takes place on the 30th December.’

Two deaths and a wedding, in a life-changing tangle. However much of a love match the new Mrs Shelley had made, hers was also a marriage of convenience, designed to prove to the Lord Chancellor that Percy was respectable enough to gain custody of his two children by Harriet. (In the event, he failed to do so.) The context was tragic, yet the marriage exciting: her child was now legitimate, and her father started speaking to her again. But, back in Bath, upheavals kept coming. On 12 January 1817, Claire gave birth to Byron’s daughter, eventually to be named Allegra. In her journal Mary glossed over this, as well as her own part in helping out, as ‘Four days of idleness.’ Only on 24 January, when William turned one, did she feel able to note, with a rare burst of feeling: ‘How many changes have occurred during this little year; may the ensuing one be more peaceful.’ ‘Nothing is so painful to the human mind as a great and sudden change,’ as she would write in Frankenstein.

Two days after William’s birthday, Mary was home in London. The strange, haunted passage in Bath was over. But she brought back with her the major part of what would become, when it was published anonymously on 1 January 1818, the book for which she is most remembered. And along with Frankenstein she brought the ‘spark’ of another life, too: for she was pregnant again. Clara would be born almost exactly a year after Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin arrived in Bath.

from the Introduction to Mary Shelley in Bath (Manderley Press, £19.99)

—

Fiona Sampson is a poet, writer and critic, and Professor Emerita of Poetry at the University of Roehampton. Her poetry collections include The Distance Between Us, Coleshill and The Catch, and she has written extensively in other genres, including In Search of Mary Shelley, a biography that offers a fresh perspective on the life and legacy of this iconic author. Mary Shelley in Bath is published in hardback by Manderley Press.

Read more

fionasampson.co.uk

@fionasampson.bsky.social

@manderleypress.bsky.social