The most Bantu of all the Swiss

by Max Lobe

The controversial poster has all tongues wagging. There are opinions of every flavour. Some say there’s nothing nasty about it. It’s just an everyday expression, they argue. A black sheep is simply someone who’s a bit different from its fellow sheep. Nothing more. Others, however, claim that it contains blatant discrimination against foreigners.

On this subject, anything is permitted. People kick the topic about. They tackle. They hurl insults. They slap one another down through interviews and posters.

Yesterday I went to Caritas to tell them I was hungry. For sure they gave me a coupon for the food bank. But they still added that my situation was made worse by the poster… Here we go again! On the train to work this morning, two young passengers, clearly friends, almost came to blows arguing about it… Upset, I changed compartments. I just needed a little break. A little moment to myself when I didn’t have to think, or speak or hear about this issue. In another compartment, I found some peace next to an elderly lady who was with a girl who must have been her granddaughter. The elderly lady immediately smiled at me. That soothed me. Then she carried on smiling at me and staring at me for the entire remainder of the journey. Weird. Why was she smiling at me so much? I wondered. Then she said, ‘You know I’m not one of those people who think you’re a black sheep, I’m not!’

In the end, I had to stand by a door waiting just to get out. Get out of this world where a poster can stir up so much feeling. But for how long?

It’s the day of the big demo against the poster of discord. At the office, we’re all prepared to go out into the streets this afternoon: banners, placards, whistles, megaphones, and above all a large dose of indignation and anger. We make the effort to learn the slogans by heart: ‘No to xe-no-phobia!’, ‘Down with racism!’

Mireille Laudenbacher is here today. More energetic than ever. There’s a chance that her dog will be spared the lethal injection. That gives her the courage and the strength she needs to take on this other fight. She goes to and fro. The clattering of her heels makes an unbearable sound. A sound that thumps me in the belly and stirs up my hunger. There’s a lot to do, but she won’t delegate anything. These are things that require experience, she replies kindly when I ask if I can give her a hand.

There’s a journalist standing in our open-plan office. He writes for a local paper, Mireille Laudenbacher whispers as she is coming and going. The guy has chubby cheeks and looks good-natured. One hand is pressing against the base of his spine and his shoulders are pulled back: this posture must be essential to support his heavy belly. I invite him to have a seat. He thanks me and sits down gingerly on a small chair which I’m now worried will collapse with a horrible crash. He tells me he’s here to interview Madame Bauer. I hope she’ll be free soon, he says. Madame Bauer is across the office. She’s being photographed, smiling, in front of the poster showing rainbow sheep and the sign saying: ‘We’re not sheep’. She’s all fired up. She’ll be even more excited when another journalist, this time from a more important daily paper, turns up. It must be hard being so much in demand, but most of all it’s such a thrill. You can see it in Madame Bauer’s eyes. She’s like a kid meeting Father Christmas.

Madame Bauer has gained recognition, not only from her fellow campaigners but also from politicians, the press and everyone who likes to express their opinion.”

But, to be honest, this hasn’t always been the case. In the early days, Madame Bauer didn’t have the opportunity to give interviews. She herself told me so. In the early days, no one took her in the least bit seriously. No one took any interest in her when, nearly forty years ago, she launched her first battles against nuclear power stations or the discharge of aluminium waste into the Rhône. People thought she was a nutter, bonkers.

They must even have thought her bitter and twisted when she demanded the vote for women in the whole of Switzerland. But all those marks of disrespect are now behind her. She has proved herself, even though she has rarely won her battles. And now, suddenly, everything has changed. Madame Bauer has gained recognition, not only from her fellow campaigners but also from politicians, the press and everyone who likes to express their opinion. And now, when there’s an issue around one of her pet causes, countless journalists come and thrust their microphone in front of her to gather her opinion. They want the view of the expert. Expert Bauer. Her opinion has become a crucial seasoning to enhance the taste of their articles and reportages.

During all the interviews she gives, I can see that Madame Bauer takes great pleasure in vehemently criticising the black-sheep poster. ‘It’s outrageous!’ she exclaims between arguments punctuated with the recent history of humanity. She vaunts the values of solidarity, respect and humanism. When she evokes those values, the traits of my Bantuland people, I say to myself that she must be the most Bantu of all the Swiss.

My belly sings.

Madame Bauer gave me the job of revamping their website, even of designing a new one. I took this task seriously. Very, very seriously. Not only because it enabled me to score my first goals, but most importantly because it was a good way to distance myself from the subject that was on the tip of everyone’s tongues. I didn’t want my three-month internship to become a work placement campaigning against a poster. When I mulled over my thoughts, I realised that this poster had a nasty odour. But is it the smell of a poster that will put food on my plate? Will it even help cure my poor mother who’s become the black sheep of the doctas in Bantuland?

I built a website which I update regularly. A website that only talks about the topic that’s trending. Despite all my efforts to shake it off, this topic is everywhere around me. The latest news is all about this evening’s demo.

Monsieur Khalifa, whom I finally met, said a big bravo! for my work. Monsieur Khalifa is a long, thin guy. He looks like a pencil. He’s a Tunisian intellectual who has been settled here among our cousins for ages. He lives in the Vaud and his accent is even stronger than that of the natives of the deepest countryside. When he opens his mouth, it sounds as if it’s Madame Bauer who’s speaking. Same tone of voice, same indignation, but above all, same idea: ‘it’s outrageous!’, ‘it’s unacceptable!’.

Today, while Mireille Laudenbacher is dealing with this sensitive matter, I spend my time reading the various online comments. On the whole, the people who visit my website are politically committed. They’ll be at the demo later.

I’m hungry.

If my belly carries on singing like this, I’ll enter a singing contest. It’s days, weeks even, since I’ve been able to afford lunch. For dinner, I make do as best I can with a cassava bobolo, grilled peanuts, pundu, or boiled potatoes. Luckily there’s a food bank distribution today. Ruedi will go and pick up our parcel.

Between responding to comments on my online forum, I write a job application. Of course I’m continuing to look for work, like the unemployment office lady said. Otherwise, in just over two months, at the end of my work placement, my belly will be singing even louder and I won’t be able to offer it a solution.

I send out countless applications. The answer is always the same.

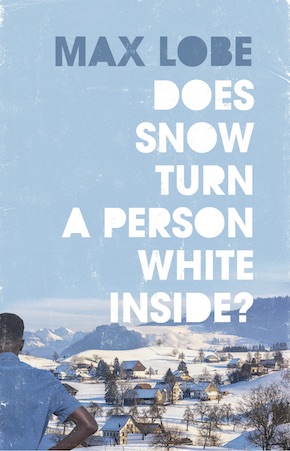

from Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside? (Small Axes, £11.99)

—

Max Lobe was born in Douala, Cameroon. At eighteen he moved to Switzerland, where he earned a BA in Communication and Journalism and a Master’s in Public Policy and Administration, and he now lives in Geneva. In 2017, his novel Confidences won the Ahmadou Kourouma Prize. His other books include 39 rue de Berne and A Long Way From Douala (Small Axes, 2021). Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, translated by Ros Schwarz, is published by Small Axes in paperback and eBook.

Read more

maxlobe.com

@maxlobe3

@hoperoadpublish

Author portrait © Guillaume Megevand

Ros Schwartz is an award-winning translator of more than 100 works of fiction and non-fiction, including the 2010 edition of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. Among the Francophone authors she has translated are Tahar Ben Jelloun, Aziz Chouaki, Fatou Diome, Dominique Eddé and Ousmane Sembène. In 2009, she was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and in 2017 she was awarded the John Sykes Memorial Prize for Excellence.

rosschwartz.co.uk