The water-god and the feathered snake

by Nick Hunt

Another man is standing guard with the usual man who is standing guard. I have not seen this man before. He is slight, narrow-faced, with a shaven upper lip.

All is well? I ask. I am not in the mood for talk but the question is a courtesy.

All is well, says the usual man. He steps aside to let me pass. The gnawed root protrudes from his teeth like a ravaged bone.

Peace be with you, says the other man.

And with you, I answer.

Where do they come from, these new men? I have given up keeping record. Every year they come and go, carried back and forth across the world, as if the caravans are rivers picking them up and placing them down. I used to greet them personally, inscribe their names in the chronicles. Merchants, traders, travellers. Now I hardly even notice them.

Your wife is back, he says.

Midway through the Caliph’s Gate I am brought up short. My wife? I say.

The woman in white. The, uh…

My wife, I say.

Yes, he says. She passed this way about half an hour ago.

A yellow lizard is creeping across the wall behind his head. The afternoon is very hot. Light dazzles off the buildings.

Why are you telling me this? I ask.

I thought you would like to know, he says.

His manner is perfectly polite. I look into his eyes but detect no guile, no mockery.

The lizard halts, advances, halts.

Very well, I say, confused.

A moment passes and no one speaks. Someone is chopping wood somewhere, a sound that is both sharp and dull. I imagine that each of us might be marking the blows inside our heads, counting up or counting down.

The lizard resumes its crawl, heading towards the shadow.

Excuse me, says the narrow-faced man. I know it is not my concern. But we heard the drums today. Has there been a Flower War?

The usual man shifts his weight from one foot to the other foot. He sucks the root between his teeth.

What is that thing? I ask him.

They sell them in the marketplace, he says. It has a pleasant taste.

There is always a Flower War, I say to the other man.

The lizard has delved into a crack, leaving nothing but its tail.

The upright scimitar declines.

And you are right, I say. It is not your concern.

Into the bowl she pours soap brought all the way from Andalus, from the luxurious bathhouses and steamrooms of the caliphate. The room is filled with the smell of roses, flowers that she has never seen.”

Malinala is in the smallest room, dressed, as the man observed, in white. You have been with the merchants, she says.

I do not know how she knows these things but she always knows these things.

I sit down upon my chair and take my sandals off. They are in the mushrik style, with soft-hard uli soles.

Yes. Now I am tired, I say.

Shall I wash your feet? she says.

I hesitate, then submit. Having my feet washed by my wife is one of my great indulgences.

She goes out into the yard and fetches a deep bronze bowl. Into the bowl she pours soap brought all the way from Andalus, from the luxurious bathhouses and steamrooms of the caliphate. The room is filled with the smell of roses, flowers that she has never seen.

She mashes the water into foam and gently takes my ankle. Her fingers slip between my toes.

That is nice, I say.

So how were the Old Men of the Nose? she asks. The name is a joke we have, from the god of merchants and travellers.

The dust and grime of Tenochtitlan commingles with the water.

The same as they ever were, I say.

Were they satisfied with the caravan?

It was a great success, I say.

Your success, she says.

Our success, I say.

Her fingers caress and probe, working at my tender soles.

Ah, I say.

It hurts?

No, no. Only as it should do.

Was Mohammed Issa asleep? she asks.

Yes, I say. No difference there.

He is getting old, she says.

Issa is no older than I am but I do not point that out. She makes circles with her thumbs, the bony heels of her hands.

What else was discussed? she asks.

This and that, I say. Market rates, the usual things. A problem with the kasava sellers.

Pah, she says dismissively. They are a bunch of Chichimecs.

Abd al-Wahid will issue a complaint, I say. They will be punished. Ah!

Her hands are pressing harder now. But the pain is a good pain.

For a while I lose myself in the sensations of the feet.

The feeling is both sharp and dull, like the rhythm of that axe. Reflected sunlight from the bowl plays across the ceiling and the walls, as if across the hull of a ship moored against a quay.

I remember the first time my wife did this for me.

She was not then my wife. We were beside a river.

Crossing through the current’s pull, I had slipped and cut my foot on a hidden edge of rock. I came limping onto shore with blood welling through my toes.

While my companions waded up, hauling their horses after them, I sat upon a rotten log and Malinala washed my feet. I did not ask her to do this. She did it without comment. First she rinsed away the blood and then she dressed the wound with leaves, green leaves from the riverbank.

The dust and grime of travelling commingled with the water.

Several of the other men laughed and made the usual jokes. I paid them no regard, as I pay them none today.

This must have been a year or more before we entered Mexica. Before we first glimpsed Tenochtitlan from the pass of the Moor’s First Sigh.

She was still teaching me to speak.

River, she said in Nahuatl, pointing to the water’s flow.

Then she said, The tree that weeps, pointing to an uli tree.

She fingered my injured toe.

Blood, she said. Blood.

Eli, she says now, which brings me back to myself. I gaze down at my feet, which gleam with scented oil. They look like idols one might find in the temple of a pampered god, basking in their own soft light. They feel new, as no other part of me feels new.

Nothing else? she asks.

Nothing of what? I say.

She has put away the bowl and is patting my ankles with a cloth.

No more a man of dust, she says. Look, I have brought you something.

As my body slackens into sleep, Malinala breathing next to me, I wonder if my bones will be buried here in the New Maghreb. And if they are, will hairless dogs bring them up again?”

Upon my desk in the largest room sits a rough clay bowl.

I lift its lid, expecting food. The bowl is full of water.

I took him from the lake, she says.

There stirs a pale, translucent shape. Four tiny hands. A smiling face.

It is a water-god, I say.

Axolotl, she says.

Bringing the bowl towards my face, I take a closer look inside. The water-god swims urgently, gliding off the sides.

Its movements are distressed but the smile does not leave its face.

I thought he might amuse you, she says. If not, we can eat him.

Only in the marketplace have I seen these curious beasts before. They are not gods, of course, but neither are they fish. They resemble illustrations I have seen of salamanders, which live in fire and are prized by alchemists. But water-gods live in the lake and are prized by the Mexica.

I have only ever seen them fried, mounded in charred pyramids, a delicacy much enjoyed at festivals and important feasts. Their flavour, I have been told, resembles that of chicken. Neither the Torah nor the Qur’an mentions them, nor creatures like them, so whether God considers them unclean I really do not know. The imam has forbidden them, but that is just the imam.

The creature’s flesh is pulpy, smooth, as lucent as my oiled feet. It wears a crown of feathered gills like the headdress of an emperor.

I will keep it as a pet, I say. When I feed it I will think of you.

The water-god looks up at me with a child’s purity.

My wife has told this tale before. It is never the same twice. Do you believe these tales? I ask. She does not recognise the question.”

Later, as we lie in bed, my wife tells the story of the Feathered Snake and the underworld.

I used to write these stories down. Now I simply listen.

Before the Fifth Sun dawned, she says, the Feathered Snake went to the place where the underworld meets the earth, and where the earth meets the sky. The Thirteen Heavens stood above and the Nine Hells lay below. He went down into the earth, through the nine layers of death, to recover the bones of mankind and bring them up to the light.

With him went the Dog-Headed God, for the Dog-Headed God is the evening star and knows his way through the dark. They travelled deep into the earth until they reached the deepest place, and there they saw the fleshless face of the Lord of the Dead.

The Lord of the Dead demanded music in exchange for mankind’s bones. He gave the Feathered Snake a flute, but the flute had no holes. So the Feathered Snake summoned worms to drill holes in the flute, and he summoned bees to make the sound of music. The Lord of the Dead gave him the bones, but only to borrow, not to keep. For in the end the bones of all things must return to death.

As the gods returned from the underworld the Feathered Snake dropped the bones, which shattered into many parts. That is why all people now are different heights and sizes. But they came safely through the dark, for the Feathered Snake is the morning star and knows his way back to the light.

On the earth, the gods drank smoke and made meal of the bones, she says. They mixed the meal with blood and maiz and shaped it into men. The Fifth Sun dawned. Men walk the earth.

But in the earth the Lord of the Dead is still waiting for his bones.

My wife has told this tale before. It is never the same twice. Sometimes the worms are ants, and the bees are flies or hummingbirds. Sometimes the morning star drops the bones and sometimes he is tricked. Sometimes he falls into a pit. Sometimes a quail startles him.

Do you believe these tales? I ask.

She does not recognise the question.

As my body slackens into sleep, Malinala breathing next to me, I wonder if my bones will be buried here in the New Maghreb. And if they are, will hairless dogs bring them up again?

I wake up later, in the dark, to hear the echoes of their howls.

And far beyond, a stony roar.

It is the mountain speaking.

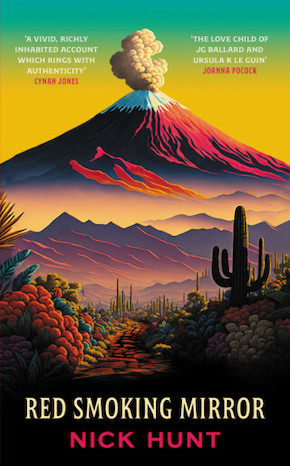

from Red Smoking Mirror (Swift Press, £14.99)

—

Nick Hunt is the author of Walking the Woods and the Water (Nicholas Brealey, 2014), and Where the Wild Winds Are (John Murray, 2017), both finalists for the Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year, Outlandish (John Murray, 2020), The Parakeeting of London (Paradise Road, 2019) and the story collection Loss Soup (Sumeru Books, 2022). Red Smoking Mirror, his first novel, is published by Swift Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

nickhuntscrutiny.com

@underscrutiny

@_SwiftPress