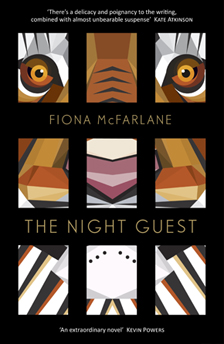

The tiger who came to stay

by Fiona McFarlaneThe main character of my first novel, The Night Guest, is a seventy-five-year-old woman named Ruth. People often ask me how it was that I came to write a book about an elderly woman. I assume they ask this because I’m not elderly; this leap of imagination, from young to old, seems particularly hard to understand. I don’t entirely understand it myself. I suspect that if I’d deliberately settled down to write a novel about a seventy-five-year-old woman, I’d never have begun, because it might seem – presumptuous? You could argue, of course, that every fictional character is a form of presumption. I would have been anxious to depict age with respect and clarity and without sentimentality. Elderly women are, so often, written as stereotypes: cranky or grand or sweet. I would have been frightened of these stereotypes if I’d thought about them when I began The Night Guest. Fortunately, that came later. All I thought about was a woman called Ruth who thinks there’s a tiger in her house at night. Beginning with Ruth, rather than ‘Old Woman’, made my task clearer: write a woman who has, over the course of eight decades, accumulated memory and experience and habit and opinion, all of it specific to her. I haven’t written an Old Woman, because there’s no one Old Woman to write. I have, I hope, written Ruth Field, who grew up in Fiji and loved Richard and married Harry and eats pumpkin seeds and likes Mozart better than Bach.

The Night Guest actually began as a short story, although it didn’t take me long to realise that Ruth and her nocturnal tiger were more than a short story’s worth of material. As the story grew longer and longer, I found that I was shy about calling it a novel. I called it, instead, ‘the Long Thing’. I’ve spoken to many other writers who, like me, seem to trick themselves into writing things as if arriving at them unintentionally. This can be a useful way of going about the preposterous business of writing a book without sabotaging yourself. In my experience, writing is almost entirely accidental and also entirely deliberate: between writing a first draft and writing a twelfth, the two strands are difficult to disentangle. I often don’t know why I’ve written something but, by the end of the revision process, I know exactly why it’s there, in that specific location, performing its specific function. It can then seem incredible that, for example, the woman called Ruth is still afraid of the nocturnal tiger; that she’s survived revision. But after many years of writing and revision (four, in my case), it also begins to feel as if there’s always been a Ruth and a tiger in this final form, and I was only writing towards them. Ruth, her magnificent carer Frida and the tiger are all larger than The Night Guest, but it was The Night Guest that made them that way. The whole process remains mysterious to me and I hope it always will.

Still, you always start somewhere, whether you know it or not. It can’t be a coincidence that both my beloved grandmothers suffered from dementia, but that’s not where The Night Guest started – at least, not consciously. It actually began with the tiger. I got interested in the number of exotic beasts in Victorian nursery rhymes and cautionary tales: elephants, crocodiles, lions, bears, and particularly tigers. Tigers stalk children’s literature, from The Jungle Book to The Tiger Who Came to Tea. The tiger is a figure of disorder. He eats antelope in Kipling and buns when he pops in for supper. He wanders the safe place of the children’s nursery, and is both exciting and terrifying. What, I wondered, would happen if I took him out of the nursery and set him loose in an adult house – the house of an elderly woman who may or may not be experiencing dementia. It was important to me, early on, that this woman have some kind of colonial childhood, so Ruth grows up as the daughter of missionaries in Fiji. Her parents named her Ruth for this reason: like the Ruth of the Old Testament, she is a stranger in a strange land. I’m fascinated by the history of the South Pacific and deliberately chose a Pacific nation in which Britain and Australia both have a colonial legacy – my tiger is, after all, a colonial one, although there are no tigers in Fiji. My tiger is always out of place, just as Ruth is when she lives in Fiji, and when she moves to Sydney, and when she finds herself old and alone in a time that doesn’t always value age.

Frida is also out of place – deliberately, it seems. She arrives at the back door rather than the front. She changes her hair colour and style on a regular basis. As the book goes on, she shows up in places she’s absolutely not supposed to. Ruth believes Frida’s Fijian, a piece of the comforting past in the present. It was a wonderful challenge to write a character who should intrigue the reader, just as she does Ruth, but at the same time remain just outside our understanding. I wanted Frida to be magnificent and strange and shifty and at the same time very human. There is care and kindness in her. The Night Guest is a book about how terrible care can be, and how careful terror.

It also feels magnificent and strange to be at this end of the process of writing a novel: to see my book as a physical object, to hear it read aloud by actors, to see it on a glowing screen that isn’t just my own laptop. Altogether, The Night Guest took just over five years from first sentence to first publication. I’ve been writing my entire life, but I still feel too new at this to give advice. The best advice ever given to me was to persevere, and I’m so glad I did.

Fiona McFarlane was born in Sydney. She has a BA in English from Sydney University, a PhD in American Literature from Cambridge University, and an MFA from the University of Texas at Austin, where she was a Michener Fellow and won the university’s Keene Prize for Literature in 2012. Her fiction has been published in the New Yorker, Zoetrope: All-Story, Southerly, The Missouri Review, and Best Australian Stories. She lives in Sydney.

Fiona McFarlane on Facebook

The Night Guest is published by Sceptre/Hodder in hardback, eBook and audio download. Read more.