No way to live like this

by John DufresneMy friend Bay Lettique, a sleight-of-hand man, does close-up magic. You can shuffle a deck of playing cards, spread them facedown on the table, and he’ll pick them up in order, ace to king, by suit or by rank, your choice. He once asked me to think of a card – not to mention it, just to picture it – and he not only identified the card, he did it by asking me to open my wallet and pull out the five-dollar bill that had the rank and suit of the card written on Lincoln’s shirt collar in red ink. Nine of diamonds. He can make a parakeet fly from his iPhone to your iPhone and from your iPhone to his shoulder. I’ve seen him slice a banana in half with a card he threw from ten feet away. At least I think I saw it. Bay says close-up works this way: I tell you I’m going to lie to you, and then I lie to you, and you believe it. Because you want to believe.

Bay used to run an illegal poker game out of a rented apartment at the Cypress Ocean Club here in Melancholy and would ask me from time to time to sit in on the game whenever he suspected someone was cheating. Could I tell him who it was? Which really meant could I corroborate his hunch. Usually I could, but too often the cheat was an off-duty Everglades Sheriff’s Office deputy or an Eden Police Department officer, which meant Bay would have to call the sheriff and make a donation to the Police Benevolent Association in order to make the cop go away without Bay himself getting busted and shut down in the process.

Now that the Tequesta Tribe has opened the Silver Palace Casino, Bay spends most nights in their poker room separating tourists and senior citizens from their money. When I remind him that those old folks might be squandering their pensions, he says he, too, wishes they wouldn’t be so reckless, but his job at the table is not to coddle them but to intimidate, infuriate, and devastate them. “I take their money or someone else does. There’s no room for sympathy in poker.” Bay is full of enthusiasms and contradictions. I worry about him. He says he can’t not be sitting at the poker table. I tell him that’s not healthy. It’s not even about the money, he says. It’s about what pumps the blood.

The call was from Detective Sergeant Carlos O’Brien of the Eden Police Department. He had a situation in the Lakes. Five bodies, one weapon, one suspect, much blood: I need you here, Coyote. Now.”

Last Christmas Eve, Bay and I sat at a sidewalk table at the Universe Café on Dixie Boulevard in Eden, drinking the last of several holiday martinis. Bay performed some magic for our waitress, Marlena. He did Four Queens, Three Ways; Maltese Crosses; Ambitious Card; and Jack Under the Plate. Marlena told us she was from Bucharest and was about to be evicted from her room at the Dixiewood Motel because she’d fallen behind on her weekly rent, fallen behind because she scalded herself in the restaurant’s kitchen and had to go to the walk-in medical clinic on Main. The Universe covered the visit but not the Vicodin. She pulled up her sleeve to show us the angry red scar. Bay asked her if she was all set for pills. Truth was she could use a couple, she said. Bay lifted his napkin to reveal two pale yellow oval tablets. Percocets okay? he said. And then he wrote her a check for the past-due rent. Marlena kissed him and wept.

When she went back to get our bill, Bay suggested that Marlena would be in need of cheering up later on. We can’t let her sit alone in a squalid motel room on Christmas Eve. This is America, for chrissakes! My cell phone played ‘Oye Como Va’. The call was from my friend Detective Sergeant Carlos O’Brien of the Eden Police Department, requesting my immediate services. He had a situation in the Lakes. Five bodies, one weapon, one suspect, much blood. “I need you here, Coyote. Now.” He gave me the address.

I checked my watch. Eleven-fifteen. “Ten minutes,” I told him.

I’m not a police officer. That evening I’d be a volunteer forensic consultant. Carlos would get my pro bono counsel, and I’d get some excitement in my unruffled life and a chance, perhaps, to see that justice was done. Sometimes I work for lawyers who are trying to empanel the appropriate jury for their clients. Sometimes I sit in my office and help my own clients shape their lives into stories, so that the lives finally make some sense. A lack of narrative structure, as you know, will cause anxiety. And that’s when I call myself a therapist. And that’s what it says on my business card: Wylie Melville, MSW, MFT, Family and Individual Therapy. Carlos used me, however, because I could read minds, even if those minds weren’t present. He said I read minds, but that’s not it, really. I read faces and furniture. I can look at a person, at his expressions, his gestures, his clothing, his home, and his possessions, and tell you what he thinks, if not always what he’s thinking. Carlos liked to call me an intuitionist. Bay said I’m cryptaesthetic. Dr Cabrera at UM’s Cognitive Thinking Lab told me I have robust mirror neurons. I just look, I stare, I gaze, and I pay attention to what I see. I’m able to find essence in particulars, Dr Cabrera said.

Carlos told me that the neighbors heard what sounded like fireworks or like gunshots around seven o’clock that evening. Pop! And then pop!-pop!-pop! And then pop! All the neighbors came out to investigate, except the Hallidays, who lived… had lived here. Mr Enzu Salazar from 723 across the street came over and rang the bell. And then he called 911. “We found this note on the kitchen table.” Carlos handed me a typed letter, and I tried to remember what I’d been doing at seven.

To whom it may concern:

To start off about this tragic story, my name is Chafin Halliday, my wife Krysia, my boys Brantley, 9, and Briely, 8, and my daughter, my precious angel, Brianna, 4. People have put obstacles in my way and no who they are. I am not insane. But this is no way to live like this. I have let my loved one’s down. I have failed at fathership. I had to die I deserved it but to love them like I do and to live without them is to hard to bare which is why we are dead and why we are together on the other side. I could not leave my babies with strangers.

Your’s truly,

Chafin R. Halliday

My first thoughts were, Here is an arrogant and sentimental man who is either paranoid or under emotional siege, a man of simple and unexamined faith whose received values fit him like a comfortable old shirt, and here is his seemingly superfluous confession, but not his explanation or apology. He can’t spell or punctuate and is curiously formal – the impersonal salutation and that affected middle initial – but not particularly insightful. Which concerned readers did he imagine he was addressing? And why on earth would he type and not write a murder-suicide note? Why no signature above the name? And that disingenuous closing that ineffectually insinuates sincerity – truly, indeed. This is a person who may have read about letters in a business English class, which he must have flunked, but who had never previously written one.

If you’re going to bother to leave a note, and you’re even going to type it up, if you’re going to take the time, wouldn’t you also take the opportunity to clarify the confounding events referred to? Instead, the writer of this note obscured rather than illuminated. He alluded to a story but omitted the first two acts. He called the killings a tragedy and not acts of senseless savagery and obscene cruelty. He muddied his motivation. He did not identify the alleged obstacles in his way or tell us who put them there. He did not explain why he thought he deserved to die or in just what way he had failed at fathership. And who uses the word fathership anyway? Hood not ship, right? Fathership sounds like the lead vessel in some intergalactic starfleet. Here’s how you write a proper suicide note:

Dear A.

As much as it hurts me to say this, I cannot join you on Saturday. When a guy doesn’t know what to say to his girlfriend anymore, then she is not his girlfriend anymore. I am leaving you the engagement ring so that every time you look at it you can think about what you stole from me.

T.

T. was a client of mine. Twenty-one when she jumped off the Cypress Avenue Bridge and hit the foredeck of a passing Bimini yacht.

***

Carlos and I stood in the sloping driveway in the Halliday front yard. Neighbors in robes and slippers gave on-camera interviews to newscasters. “You never think something like this can happen in your own neighborhood.” “A nice, quiet family.” “My boy Alex played with their kids.” “We called them the Happy Hallidays.” A hexagonal green-and-white sign by the lantana said the house was protected by Everglades Home Security. On the roof of the house, an inflatable Santa Claus sat in his sleigh and waved to us. Carlos said, “What do you think?”

I turned away from the flashing lights of the police cruisers. “I think Mr Halliday lived his real life somewhere else.”

“Do you think he did this?”

“I can’t say, but let’s suppose he didn’t. What if someone wants us to think that he did?”

“Whoever that was did a convincing job.”

“It’s easier to comprehend insanity than malevolence, I suppose.”

“It is if you’re not a cop.” Carlos took out a small pump bottle of Purell and squirted some in his hand and then in mine. “And maybe it is what it seems to be.”

“But nothing ever is.

“Who would want to kill the children?”

“Maybe it was random.”

“You’re not making sense, Coyote. Do you think our Mr Halliday could have done it?”

“Why would a man go through all of this gift-giving, all this holiday cheer, why would he buy lottery tickets, if he were planning to slaughter his family?”

“Maybe it wasn’t planned.”

Three people with filtered respirators, blue hazmat suits, and yellow chem-spill booties ducked under the police lines. Carlos said, “What the hell is this?” and yelled, “Sully, who called Mop ’n’ Glow?” He held up his hand and asked the cleanup crew what they thought they were doing.

One of them said, “What we were told to do.”

“Wait right here till I get the okay. What’s the rush?” He asked Sully to check on the cleanup with Lieutenant Romano.

“The officer inside…”

“Which one?”

“The steroid case.”

“I didn’t hear that.” He looked back at the house. “You mean Officer Shanks.”

“Officer Shanks stole a watch.”

“Are you sure?”

“He’s wearing two.”

“I’ll talk to him.” Carlos read a text message on his phone. “So what are your Christmas plans?”

“Going to Venise’s.”

“She taking her meds?”

“I hope so.”

“Inez’s not going to be happy about this. Another holiday ruined.”

“If I could get a look at some home movies or a photo album or something, it might help. Didn’t see any.”

Officer Shanks called to Carlos to come inside. I said good night and shouldered my way through the crowd. A fiftyish reporter with preposterously red hair and cat’s-eye glasses grabbed my arm, asked my name, and wrote it down. She handed me her business card: Perdita Curry, True-Crime Novels. Could it be? I thought. Factual and made-up at the same time? “I’d like to talk to you,” she said.

“That makes one of us.”

“I’ll make it worth your while.”

“So you aim to see that justice is done, Ms Curry?”

“I could pretend to want that if it makes you happy, but, actually, I just know a good story when I smell one.”

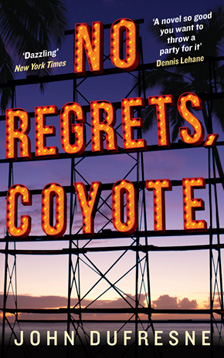

From the opening chapter of No Regrets, Coyote, published by Serpent’s Tail.

“A novel so good you want to throw a party for it. It’s tense, unnerving, fearless and funny as hell: – Dennis Lehane

Read more.

John Dufresne is the author of five novels including Louisiana Power & Light and Love Warps the Mind a Little, and two books on writing and creativity. He was a 2012–13 Guggenheim Fellow and teaches in the MFA program at Florida International University in Miami. He lives in Dania Beach, Florida.

John Dufresne is the author of five novels including Louisiana Power & Light and Love Warps the Mind a Little, and two books on writing and creativity. He was a 2012–13 Guggenheim Fellow and teaches in the MFA program at Florida International University in Miami. He lives in Dania Beach, Florida.

johndufresne.com