When time disappeared

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A vital eyewitness account of Vichy France.” Financial Times

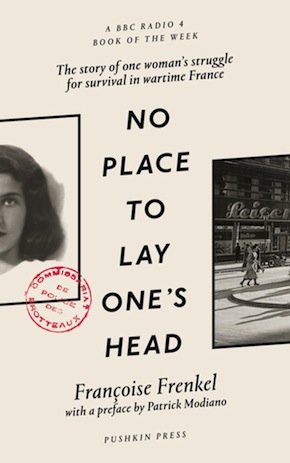

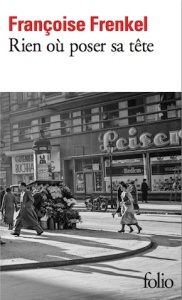

A resolute, yet equable slim volume, full of old-world poise, brimming with humanity, added itself in September 1945 to the list of J.-H. Jeheber Librairie et Éditions in Geneva. The title of Françoise Frenkel’s No Place to Lay One’s Head would appear to be affably in tune with its publisher’s ethos and history: the allusion to Matthew 8:19–20 or Luke 9:57–58 would have been resonantly clear to the readers of what began as the Librairie Evangélique de Genève in 1899, founded by Jean-Henri Jeheber, a pastor, librarian, publisher and philanthropist.

Yet inside its covers, the Son of Man is revealed to be a woman – a Jewish woman fleeing Nazi terror and world madness, all the while maintaining an unyielding vision of hope and faith, of confidence in an inherent promise of goodness in mankind, even of a certain lingering beauty, surreally juxtaposed with a reality of increasingly total blackness. No Place to Lay One’s Head is at first glance an extraordinary account not only of one human life (quite remarkable for its own sake) but of an entire era, of Europe as it sleeps through the warning signs of the rise of totalitarianism, of the savagery that would soon be so very terribly and almost incredulously unleashed. It is also a self-declared compte rendu – a testament of gratitude to those who did not fail their humanity once the artificial lull was over, and to whose kindness and self-denying courage Frenkel tells us she owed her own survival. No Place to Lay One’s Head is tacitly dedicated to the 36 tzadikim (righteous ones) existing among us at every given time, anonymous, indomitable and gently unaware of their own powers over fate and life.

As such, No Place to Lay One’s Head maintains throughout a determined purity and discretion. Even if the main character, the unwilling heroine of the story is Frenkel herself, the focus is on others – benefactors or perpetrators of lesser or greater crimes – on events, historical or personal, that will conjure up sufficiently, grippingly, momentously, the sense of biblical wilderness, but also of revelation that envelops her, and that distils the spirits of darkness and light locked in mortal struggle around her. Frenkel begins her story only at the most seminally necessary point; and she ends it precisely and hermetically where everything else that might constitute a future will begin. She spins, almost out of nothingness, a crucial moment in time that ought to suspend itself over the consciences of her readers, her fellow men, vitally, critically and irrevocably. Her text has narrative, biographical and factual economy, immense powers of engagement, but also a certain quality of bafflement. Immersed in the minutest details of her pilgrim’s progress, we also find ourselves denied of most of the presence we might otherwise yearn for. We are given only hints of a past, nothing of a future, a highly selective panorama of a present. Yet what we hold in our hands, as we hold this little volume, can be said to be pure gold.

Frenkel’s book was written with tremendous urgency and an unflinching sense of purpose, but it was completely overlooked, forgotten and overshadowed by history.”

In his rather poetic preface, Patrick Modiano proclaims that he prefers “not to know what Françoise Frenkel’s face looked like, nor the twists and turns of her life after the war, nor the date of her death. Thus, her book will always remain for me that letter from an unknown woman, a letter forgotten poste restante for an eternity.” It is a truly redolent pronouncement, yet it is also one heavily tainted by an impulse for sublimation, by an abstractionism that risks reducing this very personal story, full of universal echoes and meaning, into a mere metaphor, into a conceptual object we do not need to attach ourselves to, approach in order to reproach ourselves even, with its causes and ramifications. Modiano’s fascination with the “abrupt intimacy” and “suspended memory” of the “brief encounter” can jeopardise our sense of an ethical reality for which we are responsible. It also allows us to ignore another side to Frenkel’s poste restante – the fact that it very nearly did not make it to the eternity that Modiano so elegiacally evokes.

Rien où poser sa tête had a very short print run in 1945, and then it disappeared, like its author, until it was rediscovered in 2010 during the clean-up of a warehouse of the French charity Emmaus – an equivalent to Oxfam or the Salvation Army. Frenkel’s book was written, quite evidently, with tremendous urgency and with an unflinching sense of purpose, and published fast to be read with hope, understanding, the freedom of judgement and the potential for restitution. But it was completely overlooked, forgotten and overshadowed by history (in May 1945 Germany signed the instrument of unconditional surrender; in November, two months after the publication of Rien où poser sa tête, the Nuremberg Trials began), and also by the socio-political psychology and ethical potential of the times. Frenkel speaks not only of world trends and historical forces, but especially of private hearts and minds; she almost bypasses the momentous for the sake of individual action, inaction and responsibility. She offers recognition and thanks as well as stark witness to the chilling facility with which Nazi ideology and policies naturalised themselves in German society, how eagerly and how “rigorously and systematically” they were almost immediately implemented, not only in Germany but also in France and elsewhere; and how this transition followed on with perverse rationality from the aftermath of WWI. She does not offer lengthy theoretical analysis; instead she transcribes with terrific minuteness and equanimity the things in themselves, the minutes of the hours, the single steps of a long march that all too soon became a stampede. “This monstrous and ever-growing human termite colony spreading swiftly through the country with a sinister grinding of metal; a colony with the potential of incalculable strength.”

Frenkel creates an unreal yet perfectly palpable blend of enchantment and gloom. Her inspired foundation of a French bookshop in Berlin, the first of its kind, and a pioneer of the new strategies in world diplomacy which recommended international supremacy through cultural and commercial leadership as opposed to colonial dominion, the descriptions of Berlin intellectual life in the late 20s and early 30s, her encounters with the fashionable crowd of the German capital or with old French nobility as she flees from one hideout to another, her interactions with unknown benefactors and the bewitching landscapes she crosses on foot or by train, are synchronised with the growing power of the Nazis, their acts of viciousness, episodes of war devastation or instances of human despair and harrowing tragedy. Through all this, she succeeds in conjuring up what is most sinister in that period: the perfect normality of evil in a world so dazed and yet so intent on saving what is good.

Frenkel creates an unreal yet perfectly palpable blend of enchantment and gloom. Her inspired foundation of a French bookshop in Berlin, the first of its kind, and a pioneer of the new strategies in world diplomacy which recommended international supremacy through cultural and commercial leadership as opposed to colonial dominion, the descriptions of Berlin intellectual life in the late 20s and early 30s, her encounters with the fashionable crowd of the German capital or with old French nobility as she flees from one hideout to another, her interactions with unknown benefactors and the bewitching landscapes she crosses on foot or by train, are synchronised with the growing power of the Nazis, their acts of viciousness, episodes of war devastation or instances of human despair and harrowing tragedy. Through all this, she succeeds in conjuring up what is most sinister in that period: the perfect normality of evil in a world so dazed and yet so intent on saving what is good.

Frenkel has the talent of shadows and silhouettes, as well as of light and enchantment”

No Place to Lay One’s Head is a true human commedia, where the vis comica of life commingles stingingly with the song of woe for the annihilation that lies behind and ahead. Frenkel is anticlimactic as well as stringent in her drama, knows how to use flatness and relief to reach our innermost recesses of responsiveness and reflection. She offers a sarcastic picture of the German “art of consumption”, the arts of order, violence, intimidation, dehumanisation, even as she declares herself “lost in an abyss of melancholy”; she mesmerises and terrifies us in turn with her stories of a failed marriage of convenience to a sprightly and headstrong septuagenarian that is followed by a gulped-down Chambéry Fraise aperitif and a “peal of Homeric laughter”; of a husband who is tried for murder – for killing his wife and then failing to fulfil their pact of suicide as they flee the Nazis; of a Jewish father who kills himself because he has succeeded to cross the border to the Free Zone, while his son has been taken to the Drancy concentration camp; especially the blank space of consciousness and existence refugees seem to inhabit in Nice, their frenzy of gambling, card-playing, socialising, as they try to paralyse remembrance, reason and awareness.

Frenkel has the talent of shadows and silhouettes, as well as of light and enchantment. For vignettes of French society: the unscrupulous, libidinous ‘Marion’ who would most likely become a convenient scapegoat for French collective conscience after the liberation; ‘Madame Lucienne’, who venerates Pétain and believes in order, even crediting the directives of the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs with reason and necessary purpose, yet finds herself unable not to help the individual human being in the Jewess she knows; the mysterious ‘Madame von Radendorf’, embodying the Vienna that was strangled and erased; the self-sacrificing Mariuses, whose protectiveness has no limits during Frenkel’s months in hiding at their hairdressing salon and well beyond; also the anonymous policemen, functionaries, concierges, self-serving or self-denying, who added to or removed from the horrors and the darkness.

Thanks to Frenkel’s memoir, all this we now know; more than that, we can feel with tactile detail and resolve, with vital humanity. We do not know anything about the moment or the years after, even if we can sense the weight of conscience that is for Frenkel her own survival. History seems to have been frugal in Frenkel’s case. Even regarding the famous French bookshop in Berlin we know very little, besides what she chooses to share with us. Yet concrete documentation does exist, so we can try and imagine life on Passauer Strasse in Berlin’s affluent and culturally rich Charlottenburg (dubbed Charlottengrad because of the preponderance of Russian émigrés, including a rather dashing young Vladimir Nabokov). The KaDeWe department store is a close neighbour to Frenkel’s Maison du Livre, as is the state-of-the-art health club and gym where Marlene Dietrich went to train; and so is much of the city’s most vital Jewish life. Her bookshop offered lectures, excursions, lessons (presumably of French), it even arranged for the placement of governesses. Books and culture were powerful tools of national image-making, and Frenkel was at the heart of it.

Some scant, yet rich and resonant direct and indirect life material also exists about Frenkel herself and her husband, Simon Raichenstein, who disappears from the pages of No Place to Lay One’s Head with as much soundlessness as he did in real life. Raichenstein was born somewhere in the Russian Empire – he fled Germany under a Nansen passport, without the material resources to provide for himself in France, where he studied at the École Supérieure d’Aéronautique and then at the École Spéciale d’Électricité between 1913 and 1915. In 1921 he left with his wife for Berlin.

Françoise Frenkel may be an enigmatic absence after the war, yet we cannot fail to recognise the richness of her background in her every word, description, reflection. Hers is a society of a certain distinction and finesse, she possesses a rarefied sense of belonging, of world outlook, and of the prospects of endurance, even if the only ‘portrait’ we have of her and her husband is rather Kafkaesque: “the master and mistress of the house are Mr and Mrs Raichenstein – Russians, Galicians, or something of the sort. A strange and unsettling room, with these two, like a couple of undertakers in a funeral parlour” wrote Pierre Bertaux in 1927, cryptically, arrogantly, even meanly. Frenkel in her text possesses a definite feeling of awe for Slavic races and for her Poland in particular, for a bohemian yet aristocratic and elegant Paris, for preciously indexed collectors’ volumes. We know that she studied music in Berlin and literature at the Sorbonne; she tells us that she had always loved books, and that as a child she was given the birthday treat of designing her own glass-fronted bookcase. We can find out, if we read the histories of her native town Piotrokow, quite a great deal more: she was born Frymeta Ida Frenkel to Abraham Hensel Frenkel, a Ukrainian Jew, and Bajla Berta Horrowicz, a native of Piotrokow. Perhaps she is one of the girls in the photograph of the town’s Jewish Literary Society (above). Frenkel’s world was an extraordinary one. Her father was a banker, her grandfather Natan (Nusyn) Horrowicz was a wealthy, pious and celebrated member of his community, had a printing house, not of books but of stationery and circulars, and also a ‘Torah Talmud House’ erected in his honour; Piotrokow was a centre of Jewish publishing, of Siddur and Machzorim that proudly bore the words “Printed in Piotrokow”. Frenkel grew up in a hallowed world of stories, books, traditions and dreams, close family ties, and in a town where Jewish customs had as much presence as they had a power to liberate, inspire and send one forth into the world. Her father died in 1932 and she tells us that she is concerned throughout the war about the fate of her mother and two siblings, Mordekai Frenkel and Golda Lipski. We know that her family perished in the Holocaust, that Piotrokow was brutally ‘cleansed’, reduced to rubble, as part of the Germans’ implementation of their Final Solution. We can also dare imagine that the Frau Frenkel listed in 1929 as living in W15 Olivaer Platz 5/6 in the Jewish Address Book of Berlin of that year, might perhaps be her.

Françoise Frenkel may be an enigmatic absence after the war, yet we cannot fail to recognise the richness of her background in her every word, description, reflection. Hers is a society of a certain distinction and finesse, she possesses a rarefied sense of belonging, of world outlook, and of the prospects of endurance, even if the only ‘portrait’ we have of her and her husband is rather Kafkaesque: “the master and mistress of the house are Mr and Mrs Raichenstein – Russians, Galicians, or something of the sort. A strange and unsettling room, with these two, like a couple of undertakers in a funeral parlour” wrote Pierre Bertaux in 1927, cryptically, arrogantly, even meanly. Frenkel in her text possesses a definite feeling of awe for Slavic races and for her Poland in particular, for a bohemian yet aristocratic and elegant Paris, for preciously indexed collectors’ volumes. We know that she studied music in Berlin and literature at the Sorbonne; she tells us that she had always loved books, and that as a child she was given the birthday treat of designing her own glass-fronted bookcase. We can find out, if we read the histories of her native town Piotrokow, quite a great deal more: she was born Frymeta Ida Frenkel to Abraham Hensel Frenkel, a Ukrainian Jew, and Bajla Berta Horrowicz, a native of Piotrokow. Perhaps she is one of the girls in the photograph of the town’s Jewish Literary Society (above). Frenkel’s world was an extraordinary one. Her father was a banker, her grandfather Natan (Nusyn) Horrowicz was a wealthy, pious and celebrated member of his community, had a printing house, not of books but of stationery and circulars, and also a ‘Torah Talmud House’ erected in his honour; Piotrokow was a centre of Jewish publishing, of Siddur and Machzorim that proudly bore the words “Printed in Piotrokow”. Frenkel grew up in a hallowed world of stories, books, traditions and dreams, close family ties, and in a town where Jewish customs had as much presence as they had a power to liberate, inspire and send one forth into the world. Her father died in 1932 and she tells us that she is concerned throughout the war about the fate of her mother and two siblings, Mordekai Frenkel and Golda Lipski. We know that her family perished in the Holocaust, that Piotrokow was brutally ‘cleansed’, reduced to rubble, as part of the Germans’ implementation of their Final Solution. We can also dare imagine that the Frau Frenkel listed in 1929 as living in W15 Olivaer Platz 5/6 in the Jewish Address Book of Berlin of that year, might perhaps be her.

She provides generously, articulately, poignantly the space for secret lives, for private thoughts and feelings in a world laid open and bare to the worst but also the best of human elements.”

No Place to Lay One’s Head is full of strange and moving echoes, of people and places, an era and cultures now vanished, of literary sounds, like Édouard Dujardin’s Les lauriers sont coupés; of questions not only about history and individual biography, conscience and free will, the organic place of goodness or the omnipresence of evil, but also about the validity of a single voice in a world in shambles. Frenkel provides generously, articulately, poignantly the space for secret lives, for private thoughts and feelings in a world laid open and bare to the worst, but also, as she shows, to the best of human elements. She tragically failed to receive at the time what she defined as “the necessary complement to a book: its reader.”

This curious, gripping, delicate yet commanding memoir is the fruit of a necessity to speak, to declare one’s presence, to remember and record facts, traumas, gratitude and causation, as much as it is a forceful statement of faith in the blessing that Frenkel unfailingly believes life to be; in the possible recovery of spiritual and historical balance; in the healing of a world split in halves. It is a narrative of Germany as it falls into darkness, a chronicle of France under occupation, resistance, the insider’s story of its public and private conscience. Frenkel writes in the wake of Bernanos, Péguy, Céline, Giraudoux or Gide, alongside Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, whose works startle, shock and stagger their reader with their vehemence and darkness, their visceral anger or irreparable weight of guilt. Frenkel’s voice stands aloof and apart. It is a voice that looks across cultures and faiths, races and historical moments, uniting all that is noblest into a quiet statement of perseverance, endurance, resilience and conviction in the goodness of things and especially of humanity. A quiet voice full of turbulent reverberations, historical shadows and unquestionable enigmas, it is certainly full of allure and the deepest resonance.

Françoise Frenkel was born in Poland in 1889, lived in Paris and in 1921 set up the first French-language bookshop in Berlin with her husband. In 1939 she returned to Paris, and after the German invasion the following year fled to occupied Vichy, arriving in Nice in December 1940. Fleeing the German round-ups in the Southern Zone, she spent the last two years of the war in exile in Switzerland, where she wrote and published her memoir, before returning to Nice, where she died in 1975. No Place to Lay One’s Head, translated by Stephanie Smee, is published by Pushkin Press.

Françoise Frenkel was born in Poland in 1889, lived in Paris and in 1921 set up the first French-language bookshop in Berlin with her husband. In 1939 she returned to Paris, and after the German invasion the following year fled to occupied Vichy, arriving in Nice in December 1940. Fleeing the German round-ups in the Southern Zone, she spent the last two years of the war in exile in Switzerland, where she wrote and published her memoir, before returning to Nice, where she died in 1975. No Place to Lay One’s Head, translated by Stephanie Smee, is published by Pushkin Press.

Read more

No Place to Lay One’s Head is BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week from Monday 29 January.

Listen

Stephanie Smee is a translator of French adult and children’s books into English. Her other languages include German, Italian and Swedish.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.