All too human

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Here is the story of every fibre of our bodies.” Patrick Granville, Figaro

The French have an unflinching predilection for narratives that penetrate the veils of the private, the personal, the intimate – the vital experience of the unsayable. With dogged perseverance they will read confessions, autobiographies and diaries of all kinds, monumental epistolary collections, and torrents of conscience worthy of many Niagara Falls. They are masters of the art of authentic illusion, of a language that claims the most absolute and pure immediacy and spontaneity, which it achieves by means of superb and sparkling artifice. From graphomania to literary œuvre the path is never straight, its sublime beauty lying in its convolutions, digressions, infinite peregrinations across uncharted or far too familiar lands.

The untranslatable literary term for this self-authorising genre is journal intime – a tantalising misrepresentation of the sum of its parts, as well as a promise seldom fulfilled, yet unfailingly “the-exact-opposite-of-disappointment”, as C.S. Lewis put it.

For French writers, the journal intime is the most scarlet of red flags, the most elusive of unicorns, an irresistibly coveted golden fleece. A very special category, neither diaristic, in fact, nor confessional, the journal, unlike the traditional diary which conjures up a story, claims to create a micro-cosmology of the self, a vernacular of the unspeakable – our inner world. As such, it toys with both aesthetic expectations and artistic freedom: authenticity is the basis of its fiction and fictionality the test of its genuineness. It is personal, idiosyncratic, non-linear (not even circular), and above all it is the genre most evocative of endings – and yearned for and much doubted beginnings. It sprouts, mushroom-like, at the end of historical, cultural or spiritual eras (think of Augustine, Montaigne, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Huysmans, Proust, Valery Larbaud, Virginia Woolf or Joyce, Svevo, Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Françoise Sagan, in a single, skeletal, gigantic leap). It is an injunction to be who you are, an affirmation of the self or the reality of existence, perceived de facto to be under threat, and also a plea for empathy, a vocal demand for interest.

Resistance to this gesture of pathos and sympathy is fierce. For Roland Barthes, any self-reflexive (or self-reflective) writing has to be an anti-journal, anti-writing, if it wishes to be anything else than a narcissistic bourgeois indulgence, a self-jouissance: “in the 16th century, when people began to write [such texts] without any sense of repugnance, they called them diaria: diarrhoea and slime.” Ironically, the only kind of text that would allow Barthes to launch this virulent attack on journals and possibly on intimacy, is the journal intime intellectuel – Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes, published in 1975, which was followed by the Journal de deuil (1977–79).

Man builds houses because he is alive, but he writes books because he knows himself to be mortal, Pennac has said.”

Diary of a Body by Daniel Pennac and Portrait of a Man by Georges Perec set out to make their mark on that tumultuous tradition. Pennac’s novel (he insists it is a novel, above all) traces meticulously what he claims to be the subject that has always been left out – the physicality, pure and unadulterated, of existence, no strings (or emotions) attached. His journal is a minute cartographic exploration of materiality, a topography of the body triggered by a traumatic childhood experience that caused a split between being and consciousness, mind and body, a terror of belonging.

“I will not be afraid” become the words that make writing, thought, life possible, the catalyst between inner experience and external reality. Body and spirit catch up with each other along the way, intersect, diverge, sometimes clash and often conjoin to hilarious, gargantuan and bawdy effect. We read delighted, amused, bemused, and blushingly, thrillingly discomfited, the story of a male body laid bare, about a childhood spent with a Brechtian mother and a living-dead father whose lungs have been destroyed by mustard gas in WWI, but whose enchantment with life is stauncher than steel; about boyhood and puberty (in every detail), lust, love and fatherhood, old age and the road to mortality. “Man builds houses because he is alive, but he writes books because he knows himself to be mortal,” Pennac has said, and this is truly a paean to life and a dirge about all we miss because we are too much in a hurry, too disjunctive with what is most basic in ourselves, too insular rather than intimate. It is also a tribute to literature, to the fiction that grants reality its full value: it is perhaps only through writing, through the narrative disclosure of ourselves, that we are able to release our creative freedom but also confirm the incontestable tangibility of this extraordinary freedom to be.

Pennac ‘botanises’ existence after the manner of Rousseau, but defies any common or garden classification. His companions are his father’s aphoristic teachings, Montesquieu and Montaigne, Dickens, Stevenson, and Dumas. Yet behind the shadows lurk Fielding and Rabelais, a gregarious, Rubenesque pleasure in almost too fantastical magnifications of the most microscopic warts or curios of our mortal flesh. The plotting exercise of the physical particulars evolves expertly, mesmerisingly, into an ethnography of the social habitat of that body, into an anthropology of the soul, as it takes shape in children, grows, through transcendence and grotesque, in adulthood. Pennac is a notoriously funny writer, a conjurer of imaginary words full of bliss and sadness, irony and truth, terror and calmness. He is also a very subtle theorist of the values of literature and reading – and this is a book that deliciously follows the rules of his canon: read it in one breath or skim and skip, peruse in topsy-turvy order, enjoy at will. A Diary of a Body is a bijou intime, rarely found.

“The most welcome sum of the many parts of his rare art.” Eileen Battersby, Irish Times

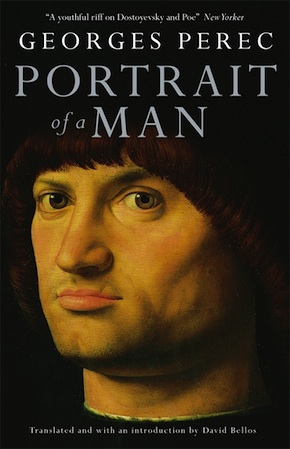

Georges Perec’s Portrait of a Man is also a story without history, a transgression of narrative conventions for the sake of a perfectly transparent voice. If the hero of Diary of a Body is on a mission to “fabricate himself a body” as Pennac has said in an interview, the task that Perec’s hero has catastrophically set himself is to fabricate an attitude, an outlook to life – a face that is as much a painted portrait as it is a lived façade. He is a master forger who has failed to produce the forgery to outdo all fakes – a real artifice of true artistic genius. Instead, he has painted a rather recognisable pastiche and committed a very brutal crime.

Portrait of a Man, the English translation of Perec’s title Il Condottiere, makes us lose some of the pugnaciousness behind the novel. The condottieri were an almost mythical renaissance category, mercenary political masterminds and wizards of the newly fashioned ‘art of war’, manipulators of fate, as Machiavelli would describe them, as much as they were legendary, fearless and ruthless leaders of men. There are several portraits of condottieri by Moroni, Bellini and Crespi, a redoubtable drawing by da Vinci, a formidable statue by Verrocchio in Venice, and more revisits of what was by then a topos, by Ingres and even Lord Leighton. A condottiere was the elusive combination of all and nothing – a precarious, magnificent balance between triumph and tragedy that Perec places at the centre of his own Portrait. At the same time, David Bellos’ choice of English title adds felicitously to the sense of ambiguity, of layer after layer of veneer and of multiple if not perfectly polymorphic identities: Antonello painted not one but at least seven ‘portraits of a man’, one of which is called Il Condottiere. All are variations on the same theme, similar in composition and even depth and ferocity; each is unique in the specific quality of omnipotent intangibility that it captures: “The Condottiere has no passion, not even for power: that is a game at which he wins every hand… his freedom is entire [just as it] became impermeable, turning hard and merciless. No cruelty, no weakness. What I wanted. Pretty much exactly what I was after.”

Perec gives us a fake journal that focuses on the genuinely unsayable, an existential portrait as much as an aesthetic one, infused with a Caravaggio sense of murderous darkness and expository light. Once more body and spirit are at strained odds, life lived and life elsewhere in a tug-of-war. Perec uses the conceit of alternating inner monologue (the I conversing with itself) and confessional or psychoanalytic dialogue to create a Kafkaesque thriller, full of horror and beauty, extreme cruelty and the most intimate humanity.

He gives us a reversal of diaristic conventions, although not an anti-diary. In a transference-countertransference model, this is a counter-diary, a diary that answers back, refuses to be written linearly, from a single optic. At its best, this is ‘prismatic’ writing, a kaleidoscope of temporalities, states of consciousness and layers, so that, as he says, “the incomprehensible [becomes] comprehensible.” Failure, in Perec, becomes a paradoxical success: Not “in the way I would have preferred… Do you see? I did succeed in painting my own portrait. I got my own face… If I’d tried for the portrait of Dorian Gray, I couldn’t have done it better…” – a statement one is tempted to say is true of Antonello’s several portraits of men as well.

There could not be two more opposite representations of ‘inner life’ – whether physical or of consciousness. In Pennac, there is a palpable joie de vivre that always overcomes every form of adversity, tragedy or hollowness, to the point that we become perhaps too sensitive to the almost total erasure of the experience of history, of suffering and pain. In Perec, on the other hand, it seems as though feeling itself, whether of joy or grief, of delight or devastation, is not even a conceivable part of reality. Perec writes under the shadow of Holocaust trauma and loss, whereas Pennac’s character fought in the resistance. A form of sublimation for one, a vice-like ring of memory for the other (forging the past or the present becomes both an act of resistance and a resignation in this sense), result in particularly moving narratives each time, of what must perforce be parallel experiences. In Pennac and Perec vis comica and vis tragica stare each other in the face – both equal reflections of human experience, and these are books to read together in order to relish what sets them apart.

Daniel Pennac’s Diary of a Body, translated by Alyson Waters, and Georges Perec’s Portrait of a Man, translated and with an introduction by David Bellos, are published by MacLehose Press in paperback and eBook.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.