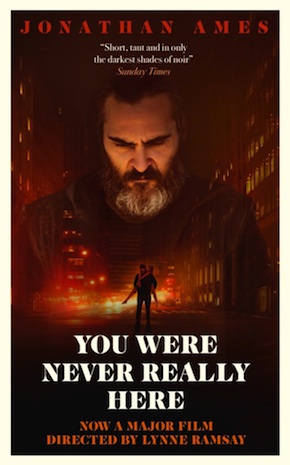

Tough love

by Jonathan Ames

“A dark thriller, full of attitude and heart.” San Francisco Chronicle

Joe felt something behind him. It was the presence of life and the coming of violence, and that anticipation, that sensitivity, enabled him to turn in time and catch the blackjack on his shoulder, which was better than taking it on the back of his head.

Also, it was his left shoulder and Joe was right-handed, and, turning around completely, he was able to grab the man’s wrist before the blackjack came down again, and they were face to face, the same height, and Joe immediately drove his forehead, like a brick, into the bridge of the man’s nose, shattering the bone, and the man, his eyes blinded by red pain, began to fall, and Joe brought up his knee, brought it up hard, without mercy, into the man’s jaw, breaking it.

The man went down completely, strings cut, lifeless but breathing.

Joe quickly swung his head to the left and the right. He was in an alley wide enough for a car. He’d come out of his flop hotel’s service entrance in the middle of the passageway, and no one was walking by or had stopped at either end. No one had seen. There was street light coming from the avenue, but the alley was mostly in shadow.

Joe wiggled his left arm, trying to get life into it, the blackjack had numbed the whole limb, and he dragged the body behind a dumpster and quickly went through the pockets of the light coat, a blue windbreaker. The fallen was a pro. No wallet. No ID. Just keys and a money clip with about two hundred dollars.

But there was a cell phone. So he wasn’t a total professional. He didn’t anticipate losing, and he didn’t anticipate being hunted, like Joe did. Joe never carried a cell phone.

He had done his job. Extracted the girl. He didn’t need to take out the one in the car. His informant had given him up, gave them his hotel, even his use of the service entrance, but that’s all they could have gotten.”

Joe looked at the blackjack. Police issue. Probably a bent cop from the Cincinnati suburbs doing a little moonlighting in the big town, where his face wasn’t known. Whoever had sent him didn’t want Joe dead. Not yet, anyway. They wanted to bring him in, talk to him. There was probably a partner waiting in a car, waiting for a call. Joe would have been spooked by a car in the alley, so this one had hidden in a cove of a doorway. He’d sap Joe and call his partner. They’d throw his body in the car and bring him to the boss.

That had been the plan. It didn’t work. Joe looked at the last text message sent: “Keep engine running. We’ll want to move quick.” “Copy” was the reply. Probably two bent cops.

The alley went one way. That meant the partner would be to the left, idling, so he could pull right in, not circle the block. Joe hesitated. He was ready to leave Cincinnati. He had done his job. Extracted the girl. He didn’t need to take out the one in the car. His informant had given him up, gave them his hotel, even his use of the service entrance, but that’s all they could have gotten, because that’s all the informant had.

Joe thought about what was in his room: a toothbrush, a new hammer, a bag, and a change of clothes. But nothing important, nothing identifiable. He had been heading out to get something to eat and was going to leave tomorrow, but he should have left as soon as the job was done. Sloppy, he thought. What the fuck is wrong with me?

Soon the one in the car would come looking. Joe didn’t want any more fights, because you didn’t win every fight. Joe figured they just wanted to know how he had gotten to them and if others would follow, and then they would have killed him. But he didn’t need to take them all out because they wanted information. He was just one man. Not the complete arm of justice. I did enough, he thought. The girl is damaged but free.

So he ran the opposite way down the alley, darted his head out fast, looking to his left and right – there wasn’t a third man guarding that end. Nobody sitting in a car, nobody planted in a doorway trying not to look like a plant. He stepped out into the street, started to walk. It was late October and there was a sweet smell in the air, like a flower that had just died. He thought about a time when he’d been happy. It had been more than two decades.

Then Joe spotted a green cab. He liked the cabs in Cincy. The cars were old and the drivers were old. It felt like the past. He got in.

“Airport,” he said, and he fingered the money clip. He’d give the driver a nice tip.

Joe lay in bed in his mother’s house. He thought about committing suicide. Such thinking was like a metronome for him. Always present, always ticking. All day long, every few minutes, he’d think, I have to kill myself.

But in the mornings and before going to bed, the thinking was more elaborate. He knew it was a waste of time – it was going to have to wait till his mother passed – but he couldn’t stop. It was his favorite story. The only one he knew the ending of for sure.

The past few weeks it always involved water. His plan of late was to slip into the Hudson at night, during high tide, by the Verrazano. The currents were strong, and he would be taken out to sea. He didn’t want anyone to be bothered with the body.

Once, when he first got out of the Marines, long before he had gone back to live with his mother, he had nearly done it. He had been processed out of Marine Corps base Quantico and ended up in a motel near Baltimore, drinking by himself for a few days and going to a movie theater, seeing the same three pictures over and over. Then one night in the motel, he had taken a lot of sleeping pills and wrapped his head in a few layers of black plastic bags, duct-taping them around his neck. He felt himself diminishing, a shadow around the edges of his mind, and he heard a voice say, It’s all right, you can go, you were never really here.

But then he clawed off the bags and pumped his own stomach. After that, the story never involved leaving a body behind, leaving a mess behind. That was shameful. When it was time to be removed, that’s what it would be – a complete erasure. So the sea would have him. It wouldn’t mind one more piece of waste. He had nowhere else to turn.

You break your adversary’s fingers, you have an immediate advantage. It frightened even the hardest men to have their fingers snapped, and in a fight, like a dance, you often held hands.”

He heard his mother downstairs and got out of bed. He did one hundred push- ups and one hundred sit-ups. His morning ritual. That, walking a great deal, and squeezing a handball as often as possible was all he did for exercise. He especially liked his hands to be strong. It was good in a fight. You break your adversary’s fingers, you have an immediate advantage. It frightened even the hardest men to have their fingers snapped, and in a fight, like a dance, you often held hands.

So his hands were weapons, his whole body was a weapon, cruel like a baseball bat. Six-two, 190, no fat. He was forty-eight, but his olive-colored skin was still smooth, which made him appear younger than he was. His jet-black hair had receded at the temples, leaving a little wedge, like the point of a knife, at the front. He kept his hair at the length of a Marine on leave.

He was half-Irish, half-Italian. He had a long, twisting Italian nose and eerie Gaelic blue eyes, set back and deep, Italian but for their color. It was a mournful face, a self-involved face, with a thick forehead, another weapon, and his jaw was too big and long, like the blade of a shovel. When he passed security cameras, he tucked it in. The black baseball hat that he wore most of the time hid the rest of his face, which in its entirety was not ugly but not handsome. It was something else. It was a mask he would tear off if he could. He was aware that he was not completely sane, so he kept himself in rigid check, playing both jailer and prisoner.

He put on pants and a T-shirt and went down to the kitchen for breakfast. His mother sat in her chair by the window in her housedress and slippers, waiting for him, patient and still, intent only on watching the door for his arrival. His plate was set. She was eighty, very short now, and had the look of a Mediterranean widow. In Genoa, where she was born, she’d be dressed in black, the widows there turning into nuns of a sort during the quiet, protracted ends of their lives.

Her silver-gray hair was piled in a knot on her head, and she wore large glasses that took up most of her sallow face, which was round and sad. Her hair, uncut for years, when set free, reached all the way to her waist. Joe had seen her once in the bathroom in her housedress – the door was slightly ajar – and her head was in the sink, she was giving herself a shampoo, and then she had risen up and thrown her hair back, like a young woman, and the hair snapped out in an arc like a long silvery rope. It struck him as magnificent. She had been beautiful once.

She got up slowly to pour his coffee and make his eggs. Behind her glasses, she looked at him with love, a slight flicker in her eyes, but she didn’t smile. That look was the only joy in his life and her only joy as well. They hardly ever spoke.

Extracted from You Were Never Really Here, now adapted by Lynne Ramsay as a major film starring Joaquin Phoenix, in UK cinemas from 9 March

Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books including Wake Up, Sir!, and You Were Never Really Here, both published by Pushkin Press. He also created the hit HBO comedy Bored to Death, starring Ted Danson, Zach Galifianakis and Jason Schwartzman, and Blunt Talk, starring Patrick Stewart. He lives in Los Angeles.

Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books including Wake Up, Sir!, and You Were Never Really Here, both published by Pushkin Press. He also created the hit HBO comedy Bored to Death, starring Ted Danson, Zach Galifianakis and Jason Schwartzman, and Blunt Talk, starring Patrick Stewart. He lives in Los Angeles.

Read more

@JonathanAmes