Twin Falls

by Shawn Vestal

“Fresh, vital and wild.” Megan Abbott

They leave the freeway and cut south through the desert. Soon the canyon comes into view, a great gray crack in the land. Crowds swarm on the far rim, and behind them a dome of trees cloisters a ranch house.

The bulge of the launchpad stands at the far end of the crowd, a mound of earth with a metal, spirelike ramp, flanked by TV trucks and a white trailer. Below, the cut basalt walls of the canyon turn back afternoon light at strange angles, silvered here, ashen there. The walls crumble downward into piles of boulder, and then stone, and then earthen slopes of weed and duff at the canyon bottom, split by the heavy, swirling Snake River.

They turn east, away from town, and enter a line of cars inching forward. Soon they hear the sound of a marching band – the harsh tin of the horns, the thump of drums. Grandpa guns the sputtering engine. To the left, in the hundred yards or so between the road and the canyon rim, crowds mill and clump; motorcycle engines whine. Beyond them is the ramp. Already, there is the Skycycle, the steam-powered rocket ship, cocked toward heaven, in red, white, and blue and with EVEL KNIEVEL spelled in golden letters and the numeral 1 on the tail fin.

“Skycycle,” Grandpa scoffs. “Nothing cycle about it.”

They come to the gate, and the man standing there with a bulging belly and hands full of bills gives their suits a second look. Grandpa hands him a fifty, then drives in, bumping across the field.

“Isn’t this ridiculous?” he asks happily as he parks.

Ahead Jason can see tent tops. People have been camping here all week, partying, drinking, fighting, skinny-dipping in the canyon pools, frightening the citizens, and upsetting the chamber of commerce.

Grandpa waves his hand at the scene. “A lot of this is exactly the sort of thing you’ve got to avoid, now that you’re getting older. Drinking and whatnot. Rowdy nonsense. But you can’t hide yourself away. You’ve got to live in this world, and keep it off you somehow. But” – and here he pats the leather block of scriptures absently, with the heel of his fist – “you ought to have a little fun when you get a chance. This ought to be fun, don’t you think?”

“I guess.”

“You guess.”

Jason blushes. He feels bashful before this strange day.

Then he emerges: Evel Knievel, flanked by two frowning men in mirrored sunglasses and cowboy hats. All attention and energy fly to him, like metal shavings to a magnet.”

They take off their coats and ties, leave them folded on the seat, and head into the crowd. Grandpa veers toward the ramp in a stiff trot, winding past guys in trucker hats and cowboy boots, long-haired kids throwing Frisbees. The crowd tightens as they draw closer, but Grandpa slips through, making a way, until they are about thirty yards from the ramp. The scene looks like something out of Billy Jack – shirtless men with long hair and beards, blurry tattoos on their forearms; women in cutoffs with wild hair; the smell of cigarettes and marijuana. It’s like nothing Jason has ever seen around here, where men wear their hair short and women wear their skirts long and most people think Richard Nixon got a raw deal. A couple of guys wearing leather vests carry girls on their shoulders, girls in tank tops without bras, and Jason studies the shift and jiggle inside those shirts. Someone calls, “Fuckin’-A!” and Jason feels embarrassed for Grandpa, imagining that he has not experienced such worldliness or that he may feel Jason has not, and Jason worries that his grandfather might regret bringing him here, might change his mind, but then the noise of a helicopter rises, a growing thwuk and drone, and a great cheer bursts forth, and it’s too late to change anything because it’s happening.

The copter tilts and drops toward the open desert on the other side of the satellite truck. TV cameras scan the crowd with their gleaming eyes. The marching band, in two shades of blue, blasts away as the copter settles, a skirt of dust billowing. Then he emerges: Evel Knievel, flanked by two frowning men in mirrored sunglasses and cowboy hats. All attention and energy fly to him, like metal shavings to a magnet. He passes along the outer edge of the crowd, dressed like anyone at the co-op on a Saturday – jeans, snap-button shirt, cowboy boots – but for a cane with a silver knob. He grasps the shaft and holds it up and the silver ball burns in the sun, channeling a pillar of light. The crowd cheers, shouts his name, and Evel Knievel and his entourage enter the trailer. The cheers fade, the band lurches to a stop.

“Well,” Grandpa says. “There he is.”

***

Jason can’t stand the waiting but he doesn’t want it to end. He feels a ludicrous faith, a sense that his future will be more like this day than anything he has experienced – all the holy Sabbaths, the constant prayer, milking and feeding, thresher and combine. The smell of cow shit rising from everything, all the time, even him, announcing his association with the lowest things. He wants to screw down this moment, keep it in front of him. The clamor, the humid press of bodies, the vault of pale sky, and the humming behind it all, the idling motor, gentle but irrevocable, the thing behind the thing, the thing behind everything, the thing that brings us what we get.

***

The bikers holler and pump their fists to the Rolling Stones, ‘Under My Thumb’ now leaking from the speakers on the TV truck. The crowd is vulgar and filthy and unspeakably beautiful. In front of them, a man in worn jeans sways to the music. His shoulder-length hair is the color of hay, the hair of Jesus Christ, and he wears a red, white, and blue headband. A cigarette dangles from his lips, goes tight as he drags, dangles again. A brown-haired girl beside him in cutoffs and a threadbare Boise State T-shirt cranes her head. She says, “Is he gonna come out or what?” and the entranced hippie says, “Are you gonna shut the fuck up or what?” and Grandpa shifts back and forth, one foot to the other, irritated.

All this waiting, all this pressure. The Sabbath feel of stalled time. And then the trailer door bangs open, and Evel Knievel hops down, glorious in the white jumpsuit with red and blue bands of stars crossing his chest like bandoliers. White boots. Tall Elvis collar open at the neck, and swooping golden-brown hair. He waves again with the cane, and plunges toward the crowd, which parts before him. The loudspeaker narrates, crackling. He seems to float, though his gait is hitched. He passes just yards from Jason and Grandpa, and they feel the backward swell of bodies. Evel Knievel comes so close Jason can see the lines on his face and his quartzite stare, and his scanning eyes stop on Jason’s. He thrusts the cane skyward, mouths something Jason cannot make out, and the gesture seems meant for him.

Evel Knievel comes closer, and Jason reaches toward him, as those around him are reaching. He waits for him to reach back, to put his hand into the striving mass of worshipping hands and to grab Jason’s one hand.

Which Evel Knievel does.

A quick grasp, one shake. The bones in Evel Knievel’s hand feel like a bundle of green branches. His eyes find Jason’s again – “Thanks for coming, buddy” – and glide away. A shout goes up: “Good luck, Evel,” and he says without turning, “It’s in God’s hands now.”

He strides into the cleared space by the ramp. The helicopter rises, dangling a basket to Evel, his hands out to the crowd as though he is blessing them. He sits in the basket and ascends, rising to the rocket ship on the ramp. Information flies, static, from the speakers. Grandpa squeezes Jason’s shoulder and Jason sees his face is wild, reverent, as he nods toward the Skycycle. Don’t miss a bit of it. The rocket reminds Jason of something from The Jetsons but cooler, finned in the rear and sleekly pointed, with the name huge on the sides and colorful ads painted around it: Mack Trucks, Chuckles candy. Evel flashes a thumbs-up from the cockpit. The crew retreats, and the Skycycle sits alone. A hushed pause, and then a revving, a sharp whine rising and rising, pressure building to a flash – the Skycycle bursts up the ramp and off, rotating gracefully, screwing itself into the atmosphere. Jason feels pinned to the earth, and his stomach fills with slither. It is like prayer, like hope, and he’ll make it, of course he will. Jason can see that in the arc of the rocket. It reigns over the earth and all its servants, a brilliant bullet aimed for the heart of the desert sky.

***

Something pops from the back of the Skycycle. What is it? The chute? A change ripples through the air. A pinprick in the pressure. The rocket slows, slows, and a white parachute drags behind it.

“Oh, my word,” Grandpa says. “For heaven’s sake.”

The rocket noses downward, drifting now toward the bottom of the canyon like a bit of burst cattail above a canal. Jason feels slapped, flattened. People race to the canyon rim, but Grandpa and Jason stay back. An eddy of body odor and cigarette smoke swirls around them. Jason fears he might cry.

Later, they drive in silence for a long time. No stories. The day has reoriented itself earthward, toward the dull and the disappointing. The truck smells like dirt. Gray dust films Jason’s shoes and socks. He stares at the delicate hem of rust lining the heater vents.

As they approach Wendell, Grandpa chuckles.

“That’ll be good for him,” he says. “Starting to believe his own bullshit.”

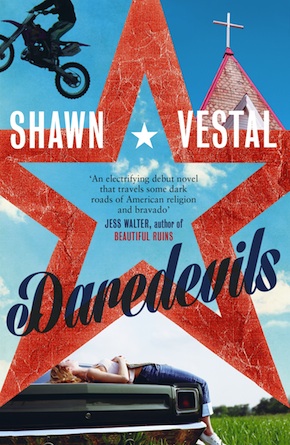

Extracted from Daredevils.

Shawn Vestal made his literary debut with the story collection Godforsaken Idaho, which won the 2014 PEN Robert W. Bingham Prize. A graduate of the Eastern Washington University MFA program, his stories have appeared in Tin House, McSweeney’s and other journals. He writes a column for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, where he lives with his wife and son. Daredevils, his first novel, is published in the UK by ONE. Read more.

Shawn Vestal made his literary debut with the story collection Godforsaken Idaho, which won the 2014 PEN Robert W. Bingham Prize. A graduate of the Eastern Washington University MFA program, his stories have appeared in Tin House, McSweeney’s and other journals. He writes a column for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, where he lives with his wife and son. Daredevils, his first novel, is published in the UK by ONE. Read more.

shawnvestal.com

Read Shawn Vestal’s Top Ten rogues’ gallery of (mostly) American showmen and charlatans.

Author portrait © Dan Pelle