Worth watching

by Brett MarieWoody Allen’s Manhattan begins with a montage of iconic New York City locations. Park Avenue, the 59th Street Bridge, the Staten Island Ferry; captured in sleek-as-silver Panavision black and white, a procession of these marvels dazzles the eye, while in our ear Allen’s voice agonises over the opening lines of a novel he’s writing. “Chapter One,” Allen repeats over and over, each time launching into a new paragraph about his protagonist’s love for the Big Apple. There’s a telling juxtaposition here: four times Allen crosses out his words, scolding himself (“Ah, corny, too corny…” “No, that’s going to be too preachy…”), before starting up again with a new and equally underwhelming passage; meanwhile, to the strains of George Gershwin, the object of his love glides effortlessly by.

On his last stab at Chapter One, Allen finally hits paydirt. Turning away from trite descriptions of “the hustle bustle of the crowds and the traffic,” he states simply: “New York was his town, and it always would be.”

I can picture Megan Bradbury sitting in a Harlem cafe, or at a desk in the New York Public Library, staring at a blank page in her notebook. There must have come a moment, at the outset of her debut effort Everyone is Watching, when she had to take a long view of the city she wanted to capture in writing, and decide where in God’s name she should start. Faced with such a monumental task, by some coincidence, she ends up aping Allen’s approach; each of her first four chapters is a different opening, a vignette that tries to tap into the city from a different angle. Each of the four chapters deals with a different historical figure, experiencing or contemplating New York in his own way. At the top of each, I can hear Allen’s voice in my head, saying, “Chapter One”:

“Robert Mapplethorpe rips out a page from the magazine and cuts around the guy’s torso, leg and dick.”

“Edmund White steps through the automatic doors of the terminal and joins the line of people waiting for a cab.”

“Robert Moses is looking out of the window of a train at the towns and villages of Long Island.”

“Richard Maurice Bucke is standing on a railway platform on a crisp, clear morning in 1891. He is waiting for Walt Whitman.”

These four icons, Mapplethorpe, White, Moses and Whitman, serve as personifications of a city too big to be contained in just one person. With each new chapter, Bradbury jumps from one to another, plotting the arcs of their lives, examining each man’s relationship to that city. It doesn’t matter that their stories never overlap more than tangentially, thematically; Mapplethorpe the photographer, White and Whitman the writers, and Robert Moses the city planner, are all merely supporting players. The real protagonist of Everyone Is Watching, straddling every scene, is the city itself.

Though uncommon, it’s not a new concept for a novel’s setting to do double duty as its star. Victor Hugo conceived his first masterpiece The Hunchback of Notre-Dame for the specific purpose of showcasing his favourite Paris landmark, and by extension Paris itself. Throughout that book, Hugo interrupts his epic story of the hideous bellringer Quasimodo and the lovely naïf Esmeralda to climb up on his soapbox and decry the disfiguring modernisations his beloved cathedral underwent between its construction and his lifetime. It’s also no coincidence that the title of the French original is simply Notre-Dame de Paris. Notre dame is kept busy throughout the story. Her gargoyles are Quasimodo’s only friends, her bells his only lovers. When the heroic hunchback steals Esmeralda from the gallows, the church becomes her sanctuary, her protector.

Moses looks upon a city that has already been built, and sets about carving into it to suit his artistic vision. His successes will alter the landscape so that future residents of that city will live partly in his shadow.”

Likewise, New York City is always there for Bradbury’s characters. For photographer Mapplethorpe, it is a frame. For the writers Whitman and White, it’s a muse. For Robert Moses, it is the canvas itself. Each of the characters’ motivations speaks to me. I’ve shared Mapplethorpe’s pursuit of the Perfect Moment, White’s desire for physical contact, Whitman’s longing for bosom friendship, even Moses’ hunger for power. Their city stirs these needs and spurs them on. It’s a feeling I know all too well.

The Moses chapters pack the most punch for me. Moses looks upon a city that has already been built, and sets about carving into it to suit his artistic vision. His successes will alter the landscape so that future residents of that city, Mapplethorpe and White included, will live partly in his shadow. But for Moses’ vision to be realised, multitudes of people, farmers and tenement residents, must be displaced. I watch him laugh in the face of a farmer he will be evicting to make way for the highway that will bring city dwellers to the beaches of Long Island. The act disgusts me, until I consider the many summer days I spent on a Long Island beach – possibly my favourite beach in the world – which bears the name Robert Moses. Of the four major characters, Moses is the most vexing – both a visionary and a villain – and it is thanks to Bradbury’s meticulous research that I can believe every nuance in her portrayal, and let myself be vexed.

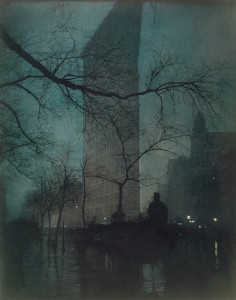

Edward Steichen: The Flatiron (1904). Metropolitan Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons

Research is one thing, but as Bradbury herself tells us, “the brain is not everything. There is also the heart.” And here is where the author’s prose comes in. Bradbury is a master of those simple, declarative sentences which seem purely utilitarian until they reveal a powerful truth. When it comes, that truth, unadorned, unshackled by sentimental verbiage, shoots off the page and pierces through my wall of cynicism. I read as she describes Edward Steichen’s photograph of a well-known city landmark: “The Flatiron Building emerges through the mist. The prow. A glorious ship coming to rest. As beautiful as any painting.” I feel a swell of love build up deep inside me. For a building.

The book isn’t perfect. Though I can sense Bradbury hovering over the text, picking her words with a watchmaker’s precision, a number of niggling details slip past her editing pen. Twice she refers the world-famous ‘I♥NY’ ad as ‘I♥NYC’, and in a book which aims to speak to us from deep within the fabric of this American city, her occasional Britishisms (calling linoleum ‘lino’, or sneakers ‘trainers’), seem jarringly out of place.

And then there is the rather myopic – even microscopic – view we get of this enormous metropolis. Partly due to Bradbury’s choice of viewpoints (an artist, two writers and a member of the political elite), her New York is weighted toward a limited demographic. The city that inspires it currently houses over eight million people, in an ethnic melting pot like few others on the planet, but this book’s population is very male, and very white. She portrays her cast with pinpoint accuracy, but what surrounds them hardly hints at the diversity of characters (black, Asian, Puerto Rican, not to mention Italian, Irish, Jewish) against whom our heroes must have bumped up at every turn in real life (the only African American character she introduces ends up literally swimming away to New Jersey after just a few pages). Absent as well is the Noo-Yawk dialect, that obtuse accent which often colours the speech of even the most cultured of its citizens, and that bluntness of tone which saves time in conversation but which so often gets them mistaken for disagreeable when outside their natural habitat. If Bradbury seeks to pull down the skyscrapers, to fold up the web of streets and avenues, and pack ten-odd million people and over a hundred years of history into two hundred and fifty pages of prose, she is doomed to fail.

But then, by that standard, doesn’t Woody Allen fail? Doesn’t Manhattan ignore the same vast swathes of the city, and is the result not all the more glaring when presented to us onscreen? Can we not say the same of The Great Gatsby? And we’d hardly expect Manhattan’s elite to populate the lyrics of the Ramones, the New York Dolls, or Run DMC. For a city so grand, so varied, so unique, where have we ever found a work of art that could contain it all?

Megan Bradbury has planted her stake deep into the city she loves.”

I have to step back and look at the Herculean feat this young author has undertaken. For her debut, Megan Bradbury has harvested a hundred little moments from a century in the life of a great city. She has articulated them with flair on the page, and arranged them into a finely-detailed portrait, one which reflects an important part of that city. She knows the importance of moments, however fleeting those moments are. Of photography, Robert’s brother Edward Mapplethorpe says at one point, “It shows something that once existed. A photograph preserves a moment in time… but that moment no longer exists.” Bradbury shows us things which once existed, and by setting them in print, she is making them in some way permanent. Robert Moses tells us, “Once you sink that first stake, they’ll never make you pull it up.” With Everyone is Watching, Megan Bradbury has planted her stake deep into the city she loves. This book is her proof: New York is her town, and it always will be.

Megan Bradbury was born in the United States and grew up in Britain. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. In 2012 she was awarded the Charles Pick Fellowship at UEA and in 2013 she won an Escalator Literature Award and a Grant for the Arts to help fund the completion of her first novel, Everyone is Watching, now published by Picador. Read more.

Megan Bradbury was born in the United States and grew up in Britain. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. In 2012 she was awarded the Charles Pick Fellowship at UEA and in 2013 she won an Escalator Literature Award and a Grant for the Arts to help fund the completion of her first novel, Everyone is Watching, now published by Picador. Read more.

@_meganbradbury

Author portrait © Alexander James

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979