The witch

by Kseniya MelnikWe set out for the witch’s house in the still-gray morning. Babushka drove, squeezed behind the steering wheel of our boxy yellow Zhiguli. Mama sat in the front, fumbling with my migraine diary. Over the last year, the doctors had failed to establish any correlation between the excruciating pain that assaulted me weekly and what and how much I ate, when and how much I slept, what I did, the season, the weather, or my geographical location. No medication had helped. The witch was our last resort.

Although my babushka, a nurse at the Polyclinika, had assured me that this witch, a good witch, a healer, had cured her friend’s heart disease, I was scared. I kept picturing the fairy-tale Baba Yaga, who lived deep inside a dark forest in a cabin held up by chicken legs. Her home was surrounded by a fence of bones, on top of which human skulls with glowing eye sockets sat like ghastly lanterns. Baba Yaga flew in a giant iron mortar, driving it with a pestle and sweeping away her trail with a broomstick, on the hunt for children to cook in her oven for dinner. Were Baba Yaga and this good witch sisters? Were all witches sisters? How often did they visit each other for tea?

The car smelled of gasoline, and a cauldron of nausea was already brewing in my stomach. I didn’t need the migraine diary to predict another cursed day. Soon the world would be ruined by blobs of emptiness, like rain on a fresh watercolor. Everything familiar would shed its skin to reveal a secret monstrous core. And, after a tug-of-war between blackness and fire, an invisible UFO would land on my head. The tiny aliens would drill holes on the sides of my skull, dig painful tunnels inside my brain, and perform their terrible electric experiments. I’d rather get eaten by Baba Yaga.

We took the same road out of the town as for our frequent mushroom-picking trips. The trees grew in two solid walls, the leaves silvering in the windy sun like coins. Mama stared out the window. After whispering late into the night, she and Babushka hadn’t said a word to each other all morning. This was a strange summer. Mama would usually accompany me on the three-day train from home to Syktyvkar, spend a week at Babushka’s, then head back to Papa and work. This time, she showed no signs of planning to leave. In fact, she hadn’t been herself all year: all the time awake, eyes and cheeks burning, telling me to remember that she loved me most of all in the world, as if she was about to die or move away.

Often, after an especially long bout of migraine, I imagined myself an orphan. How miserable and sad I would be without Mama, how feeble and helpless, and how lucky Vasilisa the Wise was in the fairy tale. Her mother had left her a magical doll, who, when fed, became alive and told Vasilisa to go to bed and not worry about anything. While Vasilisa slept, the doll did all the impossible work that was demanded of Vasilisa by her mean stepmother and stepsisters or by Baba Yaga. Oh, how I wished for a magical doll of my own.

“If you decide on it, at least make sure you don’t bring them the same gift, like your brilliant stepfather, Lev Davidovich. Twice,” Babushka said in a brash, joking tone. “Did I already tell you this story?”

Mama ignored her.

“Goes to Sweden, brings me a watch,” Babushka went on. “I look at the receipt in the box: two ladies’ watches. Gets all nervous, says they made a mistake at the register. Yes, very likely – a mistake at a Swiss register. One of the best lawyers in town and a complete idiot in life. A few months later I’m unpacking his suitcase from another business trip – two nighties. One small, one big. I leave them, see what happens. Surprise-surprise, he gives me the bigger one, the small one disappears. He wasn’t sure what size I wore, he says, so he got two. After sixteen years of marriage he wasn’t sure!”

“Quit it,” Mama said and turned back to me. “How are you feeling, kitten?”

“Another one’s coming,” I said. I missed my old, understandable illnesses – coughs, stuffed noses, ear infections. And I missed the gamelike remedies: mustard chest compresses, an orchestra of little glass cups tinkling and tingling on my back, a night spent in a headscarf soaked with vodka.

“Of course, I later gave him and that witch such a beating they took turns writing complaints to the regional Ministry of Health. Fools,” Babushka cried out. “I always had more friends than him because I am a good person. Our chief doctor, Olga Nestorovna, bless her soul, looks out for her women, always has. She knows that most men are dogs, as I say as well, except for one.” She shot Mama a look.

“The witch?” I said.

“That one’s another witch, Alinochka,” Babushka said. “A bad witch.”

“Enough. This is not helping. You’re scaring Alina.”

“I just don’t want you to do something you might regret for the rest of your life.”

“You don’t think I know that? You don’t need to torture me!” Mama yelled. My heart winced. “Stop it now. If it passes, you’ll be the first one to know, I promise. Please, let’s focus on Alina.”

“Precisely,” Babushka said.

Soon we arrived at the witch’s house. Instead of the cabin on two chicken legs like I had imagined, it was a regular izba on the edge of a small village.”

Mama climbed over into the backseat and curled up next to me, her head on my lap. This made me uncomfortably hot, but I was too weak to move.

“Don’t listen to us, Alinochka. The most important thing is for you to get better.” She kissed my hand and put it under her cheek, which was pink and covered in fine hairs, like a peach.

We stopped for a picnic lunch; I was too nauseous to eat. I wanted to crawl into a cool, dark hole and stay there with my eyes closed. My ears burned – two red signal flags for the incoming UFO.

After lunch Mama returned to the front seat, and I lay down in the back. From time to time she turned back and looked at me with worry, circling her lips with her finger. She and Babushka kept arguing, but I no longer heard them.

Soon we arrived at the witch’s house. Instead of the cabin on two chicken legs like I had imagined, it was a regular izba on the edge of a small village. The airport inside my brain pulsated with light. The UFO beamed its invisible radioactive rays at Mama and turned her into a gray rabbit, while Babushka became a brown bear. At least this was one of the less scary of their transformations.

Babushka the Bear got out the plastic bag for the witch, and Mama took my hand in her soft paw. The three of us went up to the witch’s doorstep. Babushka crossed herself and knocked. My forehead shook under the UFO’s landing gear. I closed my eyes and braced myself for the pain.

The door opened. “Hello. Come in, come in.” The witch’s voice was low and kindly. I felt a light touch on my head and opened my eyes. Instead of an old hag with rotten teeth and eyes like live coals, before us stood an orange fox in a blue house coat. She wore metal-framed glasses on her long, thin snout and a headscarf. “So, this is Alinochka, our little patient. Does your head hurt now?” I nodded. My temples had just begun to throb. “Nu, don’t be so gloomy. We’ll cure you.”

We went in. It was pleasantly dark inside. The room was dominated by a giant old-fashioned stove, on top of which Ivan the Fool, the youngest and laziest of the three fairy-tale brothers, usually snored away his days. And where Baba Yaga cooked naughty children for dinner! Orthodox icons hung in the far corner; the gold halos around the stern faces of the saints shimmered in the glow of several church candles. An episode of The Rich Also Cry, Babushka’s favorite Mexican soap opera, played on a small black-and-white TV on a bookshelf in front of the bed. I recognized the two-tone spines of the World Literature Series, the same one we had. Multicolored carpets covered the walls and the floor. It was a disappointingly ordinary home for a witch.

“Welcome. Please sit down.” The Fox turned down the volume on the TV and motioned to a table with a samovar, several teacups, and a plate laden with honey cakes. Mama smoothed her denim skirt. She looked so pale next to the lustrous Fox. I was getting a bit suspicious: in the fairy tales, foxes were crafty, treacherous creatures – probably not without a reason.

“Thank you. This is for you.” Babushka offered her the bag. I’d seen her pack a bottle of vodka and a box of chocolates along with the money.

The Fox waved it away. “Afterward, afterward. Alinochka, why don’t you sit on the bed while I talk with your mama and grandma?”

As I settled on the scratchy plaid throw, the Fox poured them some tea and added a coffee-colored liquid from a brown bottle. The black label was covered with ornate golden designs and lettering, some not in Russian. At once a sharp herbal smell filled the room, which made me nauseous again. “Now, tell me about your daughter from the beginning, from birth.”

Mama laid out my migraine diary in front of her, then hesitated for a moment, looking around the room and at the Fox with reservation, as though she’d forgotten how we got here and why. “All right. Alina was born in the winter and caught pneumonia when she was two weeks old. She skipped the crawling stage and began walking at seven months. She had already begun talking at six. Chronic sinus infections.”

She gave the dates and durations of all my colds, flus, and childhood illnesses. The Fox listened attentively, wrinkling her nose after each sip of tea. From my shadowy corner her fur appeared almost flat, like freckled human skin. Her hind paw, clad in a high-heeled slipper, danced under the table. Babushka took a big bite from a honey cake.

“As a toddler, prone to tantrums. Often in a bad mood. The migraines started a year ago, but Alina still finished first grade with all fives. The doctors advised to keep a diary.” Mama slid the diary toward the Fox. “The average episode lasts four hours, the auras before are…”

I tuned out. The aliens had begun drilling and pounding on the right side of my skull. Then they moved on to the left side. I took off my shoes and wound into a kitten ball. The Fox’s pillow was uncomfortable: hard, cold, and pierced with stems of goose feathers. My vision was full of holes. A low choral humming came from the corner where the Orthodox icons hung. I squinted to see whether the saints were moving their mouths, but their dark, mournful faces only stared, flickering in and out of the candlelight’s yellow fog.

White light strobed in front of my eyes, and the usual countdown began. Ten, nine… I jumped off the bed and stumbled toward the table, hoping to reach someone before the explosion. Babushka caught me. Eight, seven… She sat me on her sturdy knees and held me tight.

“You’re forgetting Chernobyl, Vika,” she said.

“I need to know everything before I can start the healing.”

“Alina was in Kiev,” Mama said to the Fox apologetically. “With her grandparents, on her father’s… my husband’s side. But the cloud didn’t go over Kiev. There was no direct radiation. She wore that radiation meter for months.”

I’d been four then, but I remembered that day at the zoo. I’d looked so many times at a photograph we’d taken: me sitting astride a big stuffed bear; Grandpa Sasha and Baba Lera, who had been recently diagnosed with cancer, on either side. A donkey flanked Baba Lera, and a monkey in a red vest and skullcap sat on Grandpa’s shoulder.

Suddenly, my migraine lifted. The countdown stopped, and the aliens retreated. I saw them all clearly now: Babushka, Mama, and the red-haired woman in glasses and a blue housecoat. She was much too beautiful and young to be a witch. Her pink lips were lined with maroon pencil, and a small gold cross twinkled on her freckly chest.

“We never know the whole story,” she said in a doctorly manner, the way Babushka spoke to her patients. “I don’t trust the news. I don’t trust anyone. These days we have to take matters into our own hands.”

“Exactly what I’ve been telling her,” Babushka said. “She doesn’t listen to anyone’s sensible advice. About anything.”

Mama rubbed her nostrils.

“There are many causes for ailments. But, besides a few microbial and viral infections” – the witch nodded at Babushka – “the causes are rarely biological. For one, Russia… Well, what am I saying, the whole world, the whole world is full of spirits thirsty for revenge. Wars, revolutions, genocide. The crafty ones find their way into a new life. But most are too broken. They linger around, haunt the streets, haunt our homes, contaminate the minds and bodies of the most innocent. They hide in the hollows of the heart, warming themselves in the downy scarf of a child’s soul, leaking poisons of old hurt.”

“This philosophy seems rather—” Mama began.

“Listen carefully, Vika, and think,” Babushka interrupted her, as though Mama were a disobedient child. “She is very sensitive.”

I was about to tell them that it didn’t hurt anymore when the witch called me over. She took out a measuring tape from her pocket and wrapped it around my head. I was nervous. With a magician’s flourish she showed Mama and Babushka a thumbed number. Then she dug her cold fingers into my scalp.

“Ah yes, I can see the pain now, strong pain. You poor child,” she chanted in a low voice. “The pain is like black ink, filling your head, and your head is a giant inkwell. All those spirits are floundering in the ink – I see them. They want to express their pain through you, but we will banish them out of your head – banish! banish! banish! – tell them to go and cry elsewhere!”

She encircled my head with her fingers and rubbed it, singing something folky under her breath. She smelled more like Mama than a witch – of dishwater and borsch and Lancôme perfume. She massaged her song into my head, hard and fast, now building my hair up into a crown, now letting it fall to my shoulders. “Into the forest they go! Into the forest! Into the forest!” she shrieked.

It felt good, but so what: this witch didn’t know what she was doing. She had been wrong in her diagnosis of my pain, which was gone. I was doomed.

She lifted her hands and blew hot breath on my nape.

“How do you feel?” Mama said. She was pale, her big, gray eyes shining with fever. No, I never wanted her to die or go away, even if it meant I wouldn’t get the magical helping doll like Vasilisa’s. Instead of growing up, I would shrink, I would turn into a doll myself and ride in Mama’s pocket everywhere.

She measured my head again and showed the mark to Mama and Babushka. My head had shrunk two centimeters. Maybe something had happened after all.”

““It doesn’t hurt anymore,” I said and smiled. “She stopped the pain.”

Mama jumped from her chair and clutched me to her chest. “Oh God, thank you. Thank you, Galina Kirillovna.

The witch’s name turned out to be just an ordinary Russian name. “You’re welcome. This one wasn’t too hard because she’s so young,” she said. “May your daughter grow up healthy and happy. And remember that the child’s health depends on the mother’s.”

She measured my head again and showed the mark to Mama and Babushka. My head had shrunk two centimeters. I touched it all over. Ears, mouth, nose, eyes – everything seemed intact. Maybe something had happened after all. Maybe she’d somehow altered the surface of my skull so it was now impossible for the UFO to land. I wouldn’t know until the next attack.

“Galina Kirillovna, do you by any chance do card readings?” Mama asked.

“Card readings? Of course. I do everything.”

“I wouldn’t trust the cards with such matters,” Babushka said but didn’t make a move from the table. She handed Galina Kirillovna the payment and took another honey cake.

“Alinochka, drink this and go lie on my bed. You need to rest now,” Galina Kirillovna said and gave me a cup of tea. Its bitter herbal smell made me sneeze.

My eyelids became heavy once I lay down. The bed didn’t feel as uncomfortable anymore. Through the syrup of sleep I heard the familiar incantations of the fortune-telling: For you, for the home, for the soul. What was. What will be. What will calm the heart.

…

I woke up in the back of our Zhiguli on the way home, nauseous again, this time from hunger. Babushka drove, occasionally dropping her head forward to stretch her neck. Beneath the neckline of her striped red dress she had a small fatty hump. Mama was asleep in the front seat, her face turned to me. Her lips were smiling. But whatever had calmed her heart was most likely a lie or a mistake. This Galina Kirillovna could be a healer witch or an evil witch, like the one in Babushka’s story. Or not a witch at all.

The morning is wiser than the evening, Vasilisa’s doll always said. And if the doctors can’t help and the witches can’t help, and Papa and Babushka can’t – who else is left?

The ink of the night was leaking from the corners of the sky onto the day’s bright canvas, as Galina Kirillovna would have probably said. She liked talking about the ink. Maybe she’d make a better poet than a witch.

Birches, birches, birches forever. The notches on their white trunks looked like sad black eyes. They had long tired of staring at the world without blinking, but they could never close and go to sleep.

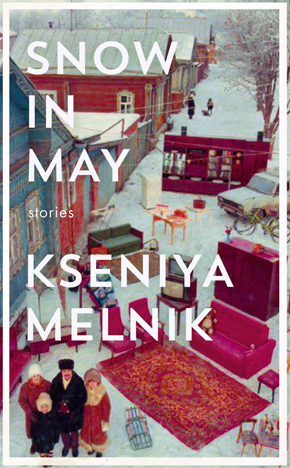

From Snow in May, now published by Fourth Estate.

Kseniya Melnik was born in Magadan in the northeast of Russia, and emigrated to Alaska at fifteen. She majored in Sociology at Colgate University then moved to New York City and worked in independent film, classical music PR, pharmaceutical sales, real estate, and at law firms, all the while participating in writing groups and taking creative writing workshops at The New School. She earned an MFA from New York University and taught introductory fiction and poetry there, as well as several private workshops online at Our Stories Literary Journal. Her work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Epoch, Prospect, Virginia Quarterly Review, and in 2010 was selected for Granta’s New Voices series. She currently lives in El Paso, Texas. Snow in May is published in the UK by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Kseniya Melnik was born in Magadan in the northeast of Russia, and emigrated to Alaska at fifteen. She majored in Sociology at Colgate University then moved to New York City and worked in independent film, classical music PR, pharmaceutical sales, real estate, and at law firms, all the while participating in writing groups and taking creative writing workshops at The New School. She earned an MFA from New York University and taught introductory fiction and poetry there, as well as several private workshops online at Our Stories Literary Journal. Her work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Epoch, Prospect, Virginia Quarterly Review, and in 2010 was selected for Granta’s New Voices series. She currently lives in El Paso, Texas. Snow in May is published in the UK by Fourth Estate in hardback and eBook. Read more.

kseniyamelnik.com