Yaddo, Yaddo

by Laura McBrideEven to me, it seems unlikely. A 50-year-old woman – with no writing history, no MFA, no closet of stories, no folder of poems – pens a novel that becomes a lead title for Simon & Schuster.

I’ve been over it a few times in my head – the parts that were amazing, the parts that were hard work, the parts that were honed craft, the parts that were sheer luck – and I think I have decided that the most unlikely, the most serendipitous moment of all, the one on which so much of the story hinges, was the moment when some unknown person chose me for a Yaddo residency.

Yaddo is one of the oldest and most famous of American artist retreats. John Cheever once wrote that “the 40 or so acres on which the principal buildings of Yaddo stand have seen more distinguished activity in the arts than any other piece of ground in the English-speaking community or perhaps the world.” It is also the place that brought me to an agent, that introduced me to working artists, and that moved me, in some basic way, from one world to another.

In addition to a beautiful and functional place in which to produce whatever sort of work they do, artists at Yaddo are given privacy, wonderful food, lovely living quarters, and clean sheets every other day. For a working mother, without any sort of home artist community, it was bliss. I didn’t know this, however, before I arrived. In fact, when I got the fat acceptance envelope, I was nonplussed. I hadn’t expected to be accepted. I had applied in part to have something concrete to write in my post-sabbatical summary. But now I would be spending four isolated weeks in a place I knew little about and could not quite imagine.

I didn’t know anyone who had ever been to Yaddo. Actually, I didn’t know anyone who had ever heard of Yaddo. The information in that one packet was scant. It appeared to be a mimeographed sheet, updated by hand, and copied again and again for decades. I thought about calling with a few discreet questions. But then, what if my acceptance were a mistake? Could the invitation be rescinded? Better just to show up at the designated time, suitcase and pen in hand. I’d bring the mimeographed letter.

I looked up Yaddo on the internet. There were lots of ghost stories. Great. I was to head across country, to a retreat without internet, to a place in the wild, with ghosts. And if not ghosts, what about egos? What if Yaddo were filled with egomaniacs, narcissists, weirdos? Artists, right?

I thought a lot about declining the offer. A mealy-mouthed thing to do, declining something one had requested for fear of ghosts. I worried. I couldn’t sleep. I bought a can of mace, some camping supplies, matches in a tin; I wasn’t sure what to expect. And I booked four tickets home. One for every Tuesday night I was there. I figured that I could survive a week of anything.

I arrived at Yaddo in mid-April. I wondered about the dark trees looming everywhere, about the sound of horses to the west, about the bedroom doors that did not lock. A fellow artist showed me around, but I didn’t ask her my questions. I made it through the first afternoon, the first dinner. I spent a terrifying first night with the sort of vivid nightmares a child has, nightmares in which a woman wearing a caftan and a turban hovered over my bed and yelled at me. The next morning at breakfast, someone asked me if I’d slept. Bleary-eyed, unnerved, I confessed to having had nightmares. Oh, several people said: “About what?” When I told them, there was a collective hush, then a murmur. Someone said “That was ——. She died in that house.” “Oh no, it was ——-. She only comes to a few artists. You must be really attuned.” “If it was her, it’s good luck. She loves artists.”

“She didn’t seem very loving,” I mumbled. And thought: I can’t last a week here.

I made it through a few more days. The room had wonderful light. It was quiet. There were birds nesting outside my window, the sculptor in the room beside mine made me laugh, I slept without visitations, a videographer smuggled me a flash drive of Game of Thrones. I was starting to like the place. One day, someone asked me if I used a pseudonym: “I can’t find anything you’ve written.” I cringed. The next day, someone else asked about the pseudonym, and I found my answer: “I haven’t published anything. I don’t know why I’m here either.” And the listener shrugged. No big deal.

I wrote like a fiend at Yaddo. I never missed breakfast – it was such a treat to be fed – and then I took my Yaddo lunchbox to my writing studio. (My studio had a turret and people called it the breast room, which someone eventually explained to me was because Philip Roth wrote The Breast there. I have no idea if this is true, but I did reread The Breast in that room, for good measure.)

I wrote wildly, freely, with the sense that what I was doing mattered to someone, with the idea that I should work at least as hard as all the folks taking care of me at Yaddo, for eight hours each day. And then I would get some exercise (hitch a ride with another artist to the Y, take a walk, or ride a bike along the trails of the 400-acre estate) and head over to dinner, eager to see my fellow artists, eager for the stories and the laughter and the ideas that 12 or 20 artists who have been intensely working all day will share. I sometimes worked in the evenings, but usually I joined other artists playing games in the West House common room, or snuck into the music hall to listen to a composer practicing, or best of all, joined another artist spontaneously sharing his or her current work with the rest of us.

Yaddo was the place at which I first allowed that what I was doing was not mere indulgence, mere time-out from my real life of teaching students and paying bills and being a responsible member of my community.”

I didn’t write the novel because of Yaddo. I would have written it anyway, though it would have taken longer, and I think I would have written the same novel. So what did Yaddo mean to me? What does it mean to this book? To this writer’s path?

Well, first, I got a lot of writing done there. I had time and space and care, and for me, those were author steroids.

And second, I made critical connections, ones I had no way to make from my own life. A fellow Yaddo writer, on learning I did not have an agent, offered to contact hers, and then another writer did the same, and then a third. My agent read my manuscript because someone she trusted had recommended it, and that someone trusted me because we met at Yaddo.

But third, and critically, Yaddo was the place at which I first allowed that what I was doing was not mere indulgence, mere time-out from my real life of teaching students and paying bills and being a responsible member of my community. What I was doing, this thing I loved to do, this thing that felt like indulgence because I loved it so much, was valuable, important work. Not my writing, per se, but that someone writes, that art is produced, that artists thrive.

Yaddo is a living embodiment that art matters. From the generous trust that created it, to the hard-working staff that coordinate the programs and maintain the property and care for the artists, to all the folks who give to support it, to all of the artists who have treasured it, Yaddo is one big billboard screaming: trying to say something true in a beautiful way is a worthwhile endeavor, all by itself.

So, I have an unlikely writer’s path. I have always thought of myself as a writer, I have always known myself to be someone who treasured words, I have spent a lifetime thinking about words, about sentences, about communication, about writing. I have read and thought and lived and waited for the chance to write. And when that chance came, when five months of glorious sabbatical, when four weeks of lovely Yaddo, came, I did not hesitate, I did not dally: I wrote and wrote and wrote. And now I have a book, and you can read it, and I am thinking of another one, of other ones. I am noting and writing and waiting: for the chance again to do something so loved.

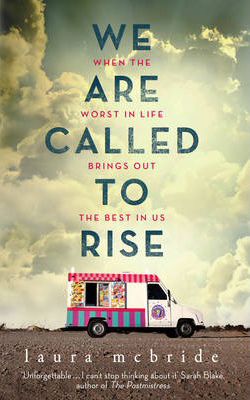

Laura McBride is a writer and community college teacher in Las Vegas, Nevada. Her debut novel, We Are Called to Rise, is a story about family, responsibility, and the power of compassion and charity (and ice cream) to rescue us from our darkest moments. Read more.