The first apparition

by Hwang Sok-yongI was attending a local kindergarten at the time, so I must have been about five years old. The azaleas had bloomed a bright red at the top of the hill, and my sisters were out filling their baskets with freshly-picked shepherd’s purse, which means it had to be early spring.

I was sitting on the sunny twenmaru porch just off the main room, basking in the warm sun, when Hindungi suddenly crossed the courtyard, heading straight for the front gate and growling. Her ears were folded back, and she bared her teeth and started barking ferociously. Wondering who it was, I went over to the gate and pushed open the wooden door. A little girl, just a bit bigger than me, was standing there. She wore a shin-length mongdang skirt and a jeogori blouse, both made from white cotton. I thought she was one of Hyun’s friends coming over to play. I said: “Hyun’s not home right now,” but the girl just stared straight at me without saying a word. Hindungi was still barking wildly behind me, but the girl didn’t look the least bit scared.

I thought I heard her say: “This isn’t the place.” No sooner did I hear those words than she turned and ran off. Actually, I’m not sure whether she ran away or faded away right before my eyes. I hurried out the gate, wondering where she’d vanished to, and saw that she was already way down at the far end of the path that ran along the other houses, which were all similar in size and shape to ours. Her ponytail swayed back and forth as she went. She stopped in front of a house with an apricot tree in the yard, turned to look my way, and slipped inside. The reason I remember that ponytail is because of the bright red ribbon fluttering at the end of it. That night, while we were all eating dinner, our mother told Father there’d been a death in the neighbourhood.

“We need to give some condolence money to the head of the neighbourhood unit. Her family just lost their grandson.”

“What? How did he die?”

Before Mother could answer Father’s question, Grandmother muttered to herself: “Must have been something in his past life. It’s fate.”

“You don’t think it’s the typhoid fever that’s been going around?”

I tugged on the hem of Grandmother’s skirt to tell her what I’d seen earlier.

“Grandma! Grandma!”

“Yes, yes, let’s eat.”

“I saw something earlier, Grandma. A little girl came to our door and then left. She went into the house with the apricot tree in the yard.”

No one paid any attention, but after dinner Grandmother pulled me aside, sat me down on the twenmaru and asked me a lot of questions.

“Who did you say you saw?”

“A little girl dressed all in white. Hindungi barked at her and tried to bite her. When she saw me, she said, ‘This isn’t the place,’ and left. I wondered where she was going so I followed her outside, and I saw her go into the apricot-tree house.”

“Did you make eye contact with her?”

“Yes! Right before she went in, she turned and looked at me.”

Grandmother nodded and stroked my hair.

“You’ll be all right,” she said. “You’ve got the gift in your blood. Now, do as Grandmother tells you. Spit on the ground three times and stamp your left foot three times.”

I don’t remember how many days I spent there. All I remember is seeing that little girl perched on the ledge of the lattice window… I wasn’t afraid.”

That day I became very ill. My body got really hot, and I started talking nonsense. It went on all night. Father carried me on his back to a hospital down near the harbour. Children and old people who’d been brought there from towns and villages nearby were lying in rows in every room. I don’t remember how many days I spent there. All I do remember is seeing that little girl perched on the ledge of the lattice window, close to where several people were lying. I stared up at her. I wasn’t afraid. After I was sent home, my sisters were moved out of the back room where we normally all slept, and my grandmother stayed by my side. She was the only one who would come near me. My fever would dip during the day and then set me afire again at night. Hives the size of millet seeds broke out all over my body and took a long time to go away. Grandmother kept asking me about the girl.

“Do you still see her?”

“No, but I did at the hospital. Grandma, who is she?”

“That’s the typhoid ghost. Nothing will happen to you. My guardian spirit is keeping watch.”

I don’t know how long I was sick. I kept slipping in and out of sleep both day and night. I can still remember the dream I had:

I enter the grounds of what looks like an old temple. A stone wall has collapsed, and tiles from the half-caved-in roof lie scattered about in the reedy, weed-filled courtyard. I don’t go into the darkened temple, but instead stand nervously next to a slanting pillar and peer inside. Something moves. A dark red ribbon comes slithering out of the shadows. I turn and start to run. The ribbon stands on end and springs after me. I run through a forest, wade across a stream and cut through rice paddies, clambering over the high ridges between them, and make it back to the entrance of our village. The whole time, that red ribbon is dancing after me. Just then, Grandmother appears. She looks different – she’s wearing a white hanbok and has her hair up in a chignon with a long hairpin holding it in place. She pushes me behind her and lets out a loud yell:

“Hex, be gone!”

The ribbon slithers to the ground and vanishes.

I woke up in a panic. My body and face were drenched in sweat as if I’d been caught in a rainstorm. Grandmother sat up and wiped my face and neck with a cotton cloth. “Hold on just a little longer, and it’ll pass,” she said.

Though I was awake, my body kept growing and shrinking over and over as the fever rose and fell. My arms and legs grew longer and longer until they were pressed up against the floor and the walls. Then they shrivelled and shrank up smaller than beans, like rolled up balls of snot dug from both nostrils, and got softer and softer until the skin burst. The warm floor against my back dropped and carried me down, down, down, into the earth below. Faces appeared in the wallpaper. Their mouths opened, and they laughed and chattered noisily at me.

I made it through the typhoid fever, but for several years, right up until I started school, I remained frail. I started hearing things I hadn’t heard before and seeing things that weren’t there before.

Extracted from Princess Bari, translated by Sora Kim-Russell.

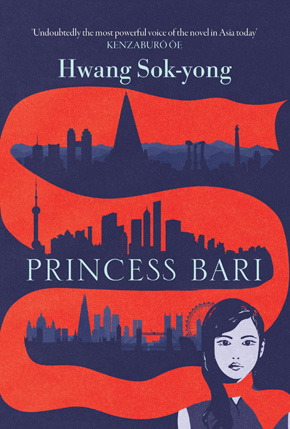

Hwang Sok-yong, one of Asia’s most renowned authors, was born in 1943. In 1993 he was sentenced to seven years in a South Korean prison for a ‘breach of national security’, having made an unauthorised trip to North Korea to promote artist exchanges between the North and South. Five years later, he was released on a special pardon by the new South Korean president. He is the recipient of South Korea’s most prestigious literary prizes, and has been shortlisted for the Prix Femina Étranger.

Hwang Sok-yong, one of Asia’s most renowned authors, was born in 1943. In 1993 he was sentenced to seven years in a South Korean prison for a ‘breach of national security’, having made an unauthorised trip to North Korea to promote artist exchanges between the North and South. Five years later, he was released on a special pardon by the new South Korean president. He is the recipient of South Korea’s most prestigious literary prizes, and has been shortlisted for the Prix Femina Étranger.

Princess Bari richly interweaves myth, magic and grim realism to make an age-old fable relevant to modern times. Out now in paperback from Periscope.

Read more.

Author portrait © Paik Dahuim

Sora Kim Russell’s translations include Bae Suah’s Nowhere to Be Found, Kyung-sook Shin’s I’ll Be Right There and Gong Ji-young’s Our Happy Time.

sorakimrussell.com