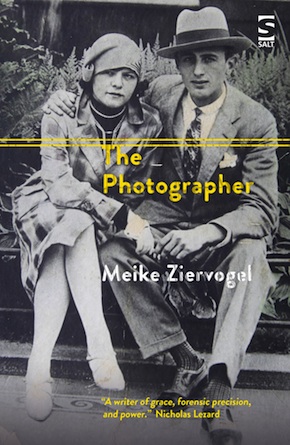

Lives in black and white

by Mika Provata-CarloneIf we seek truths, we should look into fairy tales; at least this seems to be Meike Ziervogel’s advice, as she begins her novel with the all-familiar “Once upon a time…” It is still hard for Germany to search for truths, the many sore, dark, unspeakable looming truths behind the period of National Socialism, the truths that Germans had to face about what happened before, during and after the Second World War – and perhaps it will always be so. Even harder is to tell ordinary stories, to find words that will create a new narrative fabric for old wounds and pains, an eternity of guilt, an almost mundane instinct for survival, and the natural necessity of a human future of memory and of the continuity of life.

A father with wounds from WWI and three missing toes, whose stay in the story won’t be long. A pregnant mother and a Jewish neighbour who looks after children, even though she is bitten by one to her finger-bone for being alien, strange, not quite right. Both become embedded in a world of witches and forlorn orphans, of protective dens made out of bed covers, of attachment and abandonment. History becomes refracted through the prism of a child’s overactive imagination, tragedy seems filtered through the gauze of make-believe, but the image of Germany in the mid-1920s is clear. A tremendous leap takes us to when the child Trude is now 18, precocious, uninhibited, thirsty for a life of her own. New times clash with old principles and shielding customs. Old noble blood, however (if ever) acquired, yearns for a genealogy liberated from roots, reaching out to branches only, strong and ambitious. More leaps will follow, in what is essentially a kaleidoscopic narrative, an animated contact sheet of intersecting, indivisible lives.

Children’s hiding games, fears and fearlessness, their keyhole perspective into the world of adults and of history, jarringly enhance a sense that there was never a ‘normal’ state for Germany in most of the 20th century, either before or after WWII. In The Photographer, Ziervogel achieves a level of sincerity of considerable difficulty and challenge, while remaining free of easy cynicism, sweeping pronouncements or comfortable characterisations. A pre-war Leica (a mythical Model III, perhaps?) becomes an almost enchanted object. Photography in Ziervogel’s hands is given a magician’s powers: it allows the eye defining the frame to determine the reality of the object being photographed, eternalised, confirmed in its existence, status and significance. Reality itself is subject to the photographer’s rule, through the selective orchestration of memory, through the omnipotence to proclaim borders of truth and falsehood, being and non-being. Albert, the man Trude falls in love with, has also used his camera as a shield, a hiding place, a dissociative, exonerating mechanism guarding him against the horrific heroism he was forced to document, from the glorification of insanity he was made to serve in order to survive. Once the war is over, when he returns, this refurbished, battered, war-marked, almost anthropomorphic Leica will allow Albert to remodel a world he shirks away from touching, cropping out unwanted details, developing only to the degree of clarity that the conscience of post-War Germany can sustain; reproducing scenes of perceived bliss and past meaning, as though repetition, reproduction, animistic imitation alone could restore this world of ugliness. A film roll that remains loaded yet unused becomes the metaphor of an existential paralysis but also of promise, of the instinctive readiness for life.

As each character becomes in turn the point of focus, the reader is presented with a claustrophobically narrow narrative, which often produces shocking clarity and grit, with no wide-lens views to mitigate.”

The Photographer is a novel of stark contrasts and decided graininess. Without being cluttered by constant references to the techniques of the art at its centre (or rather one of the arts at its centre), it is inherently conditioned by each and every one of its elements: control of focus, aperture, shutter speed, the surrounding light or darkness. The words feel as though they had been dipped into a succession of photographic developers, so that the end result is highly precise at the same time that it is studiedly blurry, almost doubly exposed. As each character becomes in turn the point of focus, the reader is presented with a claustrophobically narrow narrative, which often produces shocking clarity and grit, with no wide-lens views to mitigate, contextualise, annotate.

The Photogtapher is the story of Trude and Albert, and of Trude’s mother Agatha, the other magician of the story, who transforms lives by manipulating fabric, giving people their shape, content and contour where Albert gives them focus, frame, the eternity of an instant. It is the story of the boy Peter, whose innocent pickpocketing led to a family catastrophe and whose dreams of being a boxing champion offer a poignant metaphor of German urges after the war; whose pranks, fears, young love, provide an image of grim stagnation, of La Guerre des Boutons-style comic relief, but also of hope. In the background, there is the naturalised anti-Semitism of the 1930s and the unquestioned later disappearance of the Jews, there is the reality of an essentially man-less Germany: women are left behind as the men fight, die, belong, in a certain sense, to some semblance of irrational coherence. There are snippets of life after, of the disturbing intimate details of Soviet victory and the desperate flight to the western sector, of squalor, the racist hatred of post-war western Germans towards their eastern, westerly migrating compatriots inundating the cities of a divided nation; of heirloom jewellery being exchanged for food but also for high-heeled red shoes meant for dancing.

History becomes the circumstances of these individual stories, a metronome for their lives’ stages. In their indomitable will to survive, reconstruct, hold on to tatters and ruins, the forceful denial of history is at the centre. This denial betrays stark knowledge, involuntary complicity, a paralysis of inaction before the surrounding evidence of horror. How does emotional survival become possible? What is the fate of these resisting keepers of a terrible memory? Ziervogel’s flat tone, phatic narrative, accentuates this numbed acquiescence, this endurance at a heavy price. Albert and Trude, Agatha and Peter are not likeable characters. They are more often than not brutally inexplicable – and perhaps this is in itself an explanation.

There is a sense too that a world of absent men is a disordered, unruly, governless world. Men somehow bring with them structures, fixtures, certainties, whether these are deemed desirable or not. One cannot choose one’s entry into life or one’s parents, let alone one’s grandparents. And yet it would seem that one cannot ever deny the grip of these unchosen people’s stories on one’s own life. We are duty-bound to listen in full, without preening unwanted details, or washing away undesirable blemishes. We must share pain, transform it into humanity, seek sense or admit madness, confront evil and by so doing deny it its fascination and power.

Ziervogel’s plot is consciously elliptic, full of inscrutable silences, screaming questions (or accusations) and glaring absences. She succeeds in transcribing both the guttural, monistic psychology of pre-war Germans but also the mechanics of how they were precipitated into a void so irrefutably full of human presence – of all sorts. Refusing to edit or beautify through elaborate framing, she would rather capture the moment as it happens, in its ineluctable fragmentary sequence. As a novel, this reads powerfully, intriguingly, engagingly. As a human record, it has a depth of uniqueness, a perspective not often acknowledged: that of anonymous, inconsequential, commonplace Germany during the first half of the 20th century, and the exceptional, undeniable value of singular, individual lives.

Meike Ziervogel is the founder and director of award-winning independent publishing house Peirene Press. Her debut novel, Magda, was shortlisted for the Guardian’s Not the Booker prize. Her other acclaimed novels are Clara’s Daughter (2014) and Kauthar (2015). She lives in London with her husband and two children. The Photographer is published in paperback by Salt. Read more.

Meike Ziervogel is the founder and director of award-winning independent publishing house Peirene Press. Her debut novel, Magda, was shortlisted for the Guardian’s Not the Booker prize. Her other acclaimed novels are Clara’s Daughter (2014) and Kauthar (2015). She lives in London with her husband and two children. The Photographer is published in paperback by Salt. Read more.

meikeziervogel.com

@MeikeZiervogel

Author portrait © Roelof Bakker

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.