Hunters and hunted

by Mia Couto

“One of the richest and most important authors in Africa.” Henning Mankell

“Every morning the gazelle wakes up knowing that it has to run more swiftly than the lion or it will be killed. Every morning the lion awakens knowing that it has to run faster than the gazelle or it will die of hunger. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a lion or a gazelle: When the Sun rises, you’d better start running.” – African proverb

…

I peer at the village square from the top of the guava tree in the garden. I’ve never seen the shitala so full. They’ve had lunch, they’ve been drinking, and the sound of their voices has increased. I can’t see the guests who are hidden by the porch. I settle myself on the smooth trunk, and breathe in the scent of the guavas to pass the time while I wait. All of a sudden I see Archie emerge into the square to get some fresh air. He hasn’t changed much: He’s heavier, but still has the same princely air. My heart thumps in my chest. High up in the tree, I have the sensation of being above the world and time.

Suddenly I see Naftalinda crossing the square, sure-footed. What is she doing in a place that’s forbidden to women? I’ve known her ever since she was a young girl, I shared my solitude at the church mission with her. Some people say that her weight has made her mad. I have faith in her insanity. Only small fits of madness can save us from the big one.

…

The sight of the square full of people draws me back in time. I recall the occasions my grandfather, Adjiru, would come and fetch me to go for a walk in the village. Holding my hand, he would lead me to the shitala, the hall of the elders. My very presence there was a heresy that only he could authorize. The elders would ask Adjiru about his hunting adventures. At first he would hesitate. Sometimes he would pull me into the center of the gathering and proclaim:

You’re the one who’s going to tell stories, Mariamar.

But I’m a young girl, I’ve never hunted, I’ll never go out hunting…

We’ve all hunted, we’ve all been hunted, he would argue.

He was playing for time in order to become the center of the world. For later, he would draw himself up like a colossus, devoid of age, and his words would roll proudly around the room. At a certain point, Adjiru would pause, sigh, his eyes seeking out a target, suggesting that this was going to be a long story. He would sit down, sweating profusely. But it wasn’t support that he was seeking. It was a throne. Because from then on, Adjiru Kapitamoro would reign. Indeed, he wasn’t recalling the hunt: He was hunting again. In the middle of that gathering, at that very moment, before the gaze of his listeners, my grandfather lay in wait for his prey. And in its tense silence, the assembly feared putting to flight not the hunter’s memories, but the animals he was chasing.

Tell us another story, Adjiru. Tell us about that time when…

My grandfather would raise his arm in reprimand. He refused the invitation: In a hunter’s tale, there’s no such thing as “once upon a time”. Everything is born right there, as his voice speaks. To tell a story is to cast shadows over the flame. All that the word reveals is, in that very instant, consumed by silence. Only those who pray, surrendering their soul completely, are familiar with the way a word ascends and then plummets into the abyss.

…

You shouldn’t trust the hunter, he admitted. Not because the hunter is a liar. But because hunting contains the truth of a dance: bodies in flight from their own reality.”

One night, the story had been going on for a long time, and everyone was well oiled with drink, when Genito Mpepe, his voice slurred, interrupted:

Hey, there, Adjiru! You’re a hell of an imposter!

It was like a stone thrown into a puddle without any water. Adjiru’s astonished look was like a wound ready to be opened. Raising his finger, he declared rancorously:

You, Genito, have just snapped the fork when it’s still in the mouth.

Shattered, my grandfather withdrew from the shitala and melted into the night. Only I went with him. I sat down in the dark and waited for him to speak. Finally, after a long pause full of sighs, he complained:

Why? Why did Genito do this to me?

My father’s drunk. Ungrateful.

Ungrateful, the lot of them. What they call lies, I call gifts.

His gaze became lost in infinity. A thousand thoughts swept through Adjiru, a thousand memories. Gradually, his anger subsided.

Do you know something, Mariamar? The saddest thing is that Genito may be drunk, but he’s right. All that bragging in my tales: It’s all smoke and no fire.

You shouldn’t trust the hunter, he admitted. Not because the hunter is a liar. But because hunting contains the truth of a dance: bodies in flight from their own reality. This was how Adjiru understood it.

At that moment, in the now-empty hall, I watched my grandfather Adjiru as if he were a little boy, more solitary and vulnerable than I was.”

In fact, he explained, a hunter’s career is made up of fiascoes and forgetfulness. No matter how perfect his aim, a man who hunts is a bungler. For one victory, he has to suffer a thousand defeats. That’s why the hunter is an inventor of his own prowess: because he doesn’t believe in himself, because he’s more fearful of his own weakness than he is of his most ferocious prey.

I’d rather be a liar. For, at heart, I’m nothing. I’ve never done anything.

Don’t say that, Grandfather. You’ve done so much hunting.

Do you want to know something, dear granddaughter? In hunting, the prey works harder than the predator.

He wasn’t complaining. Deep down, his ambition was to be free of all obligations. Happiness, he used to say, consists in not doing anything: To be happy is merely to let God happen. And he fell silent, his hands nervously rubbing his knees.

Suddenly he jumped to his feet, decisive, as if visited by some new spirit. And with firm step, he set off again for the assembly hall. Climbing up on a chair, he puffed out his chest and faced the crowd.

Do you want stories? Well, I’m going to tell you a story. Your story.

Here we go again, some mumbled.

Have you forgotten you were once slaves? Adjiru continued.

We’re doomed, others commented.

Or have you forgotten that we were once taken across the ocean? None of us came back. Or have you forgotten about my father, Muarimi Kapitamoro? He was taken to São Tomé, remember?

We’re going, the men shouted in chorus. And, turning to me, they added: Come with us, because the words are going to fall thick and fast now.

One by one they walked off, until I was the only one left in the hall, my heart in my hands, as I stared at the wobbly chair on top of which my grandfather continued his impassioned rhetoric. I even dared, with timid voice, to call him back into the world. But at that moment, I was invisible to him. An enraged prophet had taken possession of my old relative.

Do you know why the slaves left no memory? Because they have no grave. One of these days, here in Kulumani, no one will have a grave anymore. And there will no longer be any memory that there were once people here…

Grandfather, let’s go home.

Nowadays, we don’t even have to be put on ships. São Tomé is right here, in Kulumani. Here, we all live together, the slaves and the slave owners, the poor and the owners of the poor.

…

At that moment, in the now-empty hall, I watched my grandfather Adjiru as if he were a little boy, more solitary and vulnerable than I was. I walked over to the chair that was his stage, and reached up to touch his hand.

Come, Granddad. Let’s go home.

Arm in arm, we walked along the path next to the river.

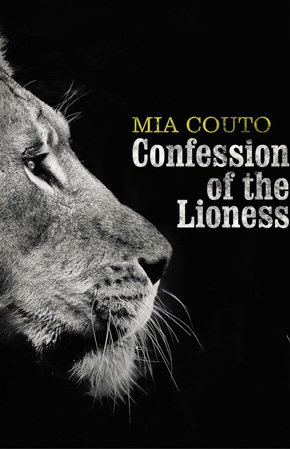

Extracted from Confession of the Lioness, translated by David Brookshaw.

Mia Couto, born in Mozambique in 1955, is one of the most prominent writers in Portuguese-speaking Africa. His books are deeply rooted in the political upheavals, languages and narratives of his native land, and have been published in more than 20 countries. He has won many awards, including the 2014 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and was shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker International Prize. He lives in Maputo, and works as a biologist. Confession of the Lioness is published in hardback and eBook by Harvill Secker and Vintage Digital. Read more.

Mia Couto, born in Mozambique in 1955, is one of the most prominent writers in Portuguese-speaking Africa. His books are deeply rooted in the political upheavals, languages and narratives of his native land, and have been published in more than 20 countries. He has won many awards, including the 2014 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and was shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker International Prize. He lives in Maputo, and works as a biologist. Confession of the Lioness is published in hardback and eBook by Harvill Secker and Vintage Digital. Read more.

Author portrait © Daniel Mordzinski

David Brookshaw is an emeritus professor at the University of Bristol. He has published widely in the field of Brazilian and Lusophone Postcolonial Studies and his recent translations also include Mia Couto’s The Tuner of Silences and Pensativities: Selected Essays.