Nathalie

by Catherine McNamara The plane was held up in Lomé. Mona didn’t bother leaving the house. She checked that Miguel was sleeping. He was: the slow fan wheeled above him, his hand clenched a shroud of mosquito netting which she loosened and let drop. She went out to smoke on the terrace, the city air a giant belch of open sewers and fried food, a gassy decomposition. Mona had seen travellers gag at the channels of waste snaking through the city. Where old women straddled and pissed, where a fallen coin might well have plopped into magma. But for her it was the most acute of honesties, the travails of the city were naked.

The plane was held up in Lomé. Mona didn’t bother leaving the house. She checked that Miguel was sleeping. He was: the slow fan wheeled above him, his hand clenched a shroud of mosquito netting which she loosened and let drop. She went out to smoke on the terrace, the city air a giant belch of open sewers and fried food, a gassy decomposition. Mona had seen travellers gag at the channels of waste snaking through the city. Where old women straddled and pissed, where a fallen coin might well have plopped into magma. But for her it was the most acute of honesties, the travails of the city were naked.

Nathalie called again and Mona’s stomach eased. The plane had landed, she sounded intact. Frankly, Mona was relieved she would not have to spend the night visualising local technicians fingering the plane’s entrails on the tarmac. She could sleep. From the liveliness in Nathalie’s voice she must have met some fellow traveller on the flight and shared the wait. Envy flickered. The only people who talked to Mona on planes were women as chiselled as herself. They were a robust tribe, nationless and colourless, they made lean talk.

She parked in the new car park and shushed away the watchmen closing around her. She pointed at a bright-faced one and the others slouched away. She strode up to the dense triptych of the airport entrance and recognised her daughter to one side talking to a tall man, a returnee she ventured

“Maman!” Nathalie broke free, nestled her face in Mona’s neck, the shameless child who used to sit on her belly and tweak her nipples. “Tout va bien pour toi? Et Miguel? Is he asleep at the house?” She placed her cheek against Mona’s, her skin still so soft, a loving gesture.

“This is Seth, Maman. His family is from here. He’s working in Paris too. He is here to do some work up north.” Nathalie made space for Seth’s long arm to wend out and their hands shook. Mona’s thoughts: edgy, cool, burning for success. They would sleep together before either of them flew out.

Seth had a ride coming in from Teshie, an aunt who was a nurse. He was fair, with a drop of milk in his skin and trendy thick-rimmed glasses. Mona was staring. Chaos surrounded them now. Another plane had released its passengers and they pushed as a many-headed mass through the glass doors as fakirs stormed towards them.

She wanted to take Nathalie home, to have her on the terrace sipping a mug of green tea. She tugged on Nathalie’s arm.

“Miguel is alone,” she said.

“Of course! Seth, I’ll call you tomorrow, d’accord? We’ll most probably go to the beach, okay Maman?”

Mona took Nathalie’s camera bag and pushed past the hustlers and vendors, down the steps and under the neem trees back to the car park. She didn’t want Nathalie to see the tears that had sprung into her eyes. Her jealous tears. She had wanted Nathalie to herself.

In the car Nathalie chattered. “I was so certain we would be catching a bus from Lomé! You have no idea how full the plane was until Abuja! I’d forgotten. It’s been too long, hasn’t it Mona? Just how have you been in your little house on the roof? Are they paying you properly in that silly school? Does your lover still visit you when Miguel has gone to sleep?”

She pinched Mona’s side and Mona could feel the skin stretch. Months ago now, her lover had returned to his village when his young girlfriend died delivering twins. He had asked Mona for money and disappeared, leaving Mona feeling robbed.

“How long can you stay in town this time? You’re not going to go north with that guy?” Mona said.

‘Oh, Maman! He’s a photographer. It will be good to work with someone else. He has funding, you see. He is working on a book.”

“What of Xavier?”

“It’s over, Mona. I told you that. Don’t make me go there again.” Nathalie spilled a knot of tobacco into a skin and rolled up fast. “Here Mona, take a drag on this.”

Mona inhaled. It rushed across into her blood.

“How is that little monkey, Miguel? Is he still your sweetbread?”

The truth was that Miguel was a challenge. He had the same flints in his eyes as his father. He was disobedient. He loved to trick her, lie to her. Mona began to cry in the dark.

“Oh, choux!” Nathalie touched her hair, smoothed her neck. “Don’t cry, Maman. It will be okay. I’ve missed you so hard. Now we will be together.”

They brought her bags up the damp concrete stairwell to Mona’s haven at the top. Four rooms, a detached shower and washroom, the apartment was an afterthought on top of the block, with broad views from the blurred sea line to the horizon of cheap cement houses spotting the scrub. But it provided the sky at all hours, in all her moods. Mona prepared tea while Nathalie tickled Miguel in bed. Later they sat out there in silence, Mona having forgotten all she had wished to say to her.

*

Miguel charged into her room and wriggled under the thin sheet. Mona had put Nathalie in her studio, where there was a spare mattress propped behind her easels. Last year Nathalie had brought her new boyfriend Xavier with her and they’d been intertwined, interchangeable, every comment and glance. Mona, whose loves had been unequal and endured, adored their complicity. But something had erased what had thrived between them. Nathalie had moved on and Xavier was a thing of the past.

Miguel pinched her soft stomach. “This is my home, Maman! My old house! Wake up so we can go to the beach!”

She felt his wet breathing on her neck. The two of them, Nathalie and Miguel, were the only ones who still identified the parts of her body. Her used breasts, her shrunken womb, her thickening middle.

“Get off me, Miguel. You’re too hot.”

Here there were colonial villas painted toothpaste blue, flaking stucco archways and statues dappled with tiles… lopsided hotels from the post-Independence years with dry shattered swimming pools and perilous diving towers.”

She was surprised to see Nathalie in the kitchen in a T-shirt and shorts, her city skin so pale.

“Bonjour Maman! I’ve just called Seth. You don’t mind if he joins us at Kokrobitey? I know you will like him. Look! Here is your present. I brought you some tools and paints.”

Nathalie opened the box of Japanese tools and Mona saw knives for slicing through linoleum, scalpels for her buttery paintings. The gleaming tubes in a row.

“And I saw your work in the studio – just a little – you must show me afterwards. I am so happy to see you are working!”

In an hour they were deep in the sluggish traffic through Kaneshie, the market thronging, churchgoers pacing along the overhead bridge, mothers close to the kerb with dangling children sashed to their backs. If Mona painted here it was because at home she was constricted, she could hardly explore her compulsion. Here she had found colonial villas painted toothpaste blue, and flaking stucco archways and statues dappled with tiles. There were lopsided hotels over the Atlantic from the post-Independence years, with dry shattered swimming pools and perilous diving towers.

Mona worked hungrily. In the beginning, nobody but Nathalie knew. After school Miguel went downstairs to kick a football with the children from the block and she went into the hot little room with its ceiling fan and glass louvres rusted into place. She sketched, she worked from photographs. The young boxers in the square, their faces twisted masks. Children soaped along the fetid canal while in the background football players scrambled in the dust.

“Miguel, have you been looking after Maman for me?” Nathalie had asked her brother about the schoolteacher he detested, and before that about the dog downstairs that had disappeared. Of their two fathers, Miguel’s had been more passionate, but crueller. He had grafted Mona onto his life when his partner had left him. Slowly, he had enthralled her, leached her, had almost stolen the child.

“Where is Xavier?” Miguel had asked.

“Xavier has gone back to his old girlfriend,” Nathalie finally revealed to them both. “He’s gone back to London.”

The road behind the beach huts was sandy and knotted with bumps. Mona’s low Lada revved and laboured along the woven palm-leaf fence on one side that marked out the private plots of the foreigners. Diplomats had started to upgrade the area with concrete weekenders fanning out from the coast, some with walls crenulated with broken glass and uniformed watchmen carrying batons. Mona had been lucky. She’d been handed down an unpretentious wooden hut by the cultural envoy at the embassy. He hadn’t liked his successor and had offered it to her. Sitting at the end of the dirty sweep of beach, for the moment it was the last construction before the rocky point.

She pulled into a gap in the fence but there was a car parked in her spot, a little white Suzuki with churchgoers’ stickers on the back window. The auntie from Teshie. Seth had borrowed a car. Mona looked around for him and there he was, stepping off the porch to greet them.

“Who’s that?” said Miguel. “There’s someone in our house!”

“It’s okay, Miguel. It’s my friend Seth. He was on the plane with me from Paris.”

Nathalie hopped out quickly and they strode towards each other, exchanging kisses on the cheek. Miguel stared.

“Come on, Miguel,” Mona said. “Help me with the bags.”

A shirtless villager rushed up behind the car. It was Jacob, their watchman, wearing a pair of Mona’s old shorts with a woman’s plaited leather belt. He opened the boot and brought Mona’s cool box and baskets up the steps, fishing for the keys in his pocket.

“Hello again, Mona,” said Seth.

“Seth, this is my little brother Miguel,” Nathalie said, holding her brother’s shoulders. “Miguel, meet Seth.”

Miguel sized up the tall man with an impressive Leica on a strap around his neck. For years now Nathalie had no longer lived with them and her visits were short, exquisite eddies. The last time she and Xavier had left Miguel had shouted at Mona, he had screamed and sobbed at her on the terrace until he had crumpled into a chair and slept. Miguel turned away from the pair. He ran down onto the sand to play.

Briefly, Nathalie helped Mona unpack. But Jacob took over, flinging out the printed tablecloth and pegging it in the wind, putting out glasses and a jug of cool water immediately. After years in the employ of her high-ranking predecessors, Mona had failed to rewire his zest. Sometimes she sat back and was grateful for it. Twice, though she shrank to think of it now, she had paid Jacob to keep away. She had sent Miguel to a friend’s house and had brought her lover here. The young man had waded into the thick night waves, beckoning her. She had thought of their bodies washed up in a putrid cove in the city.

Mona opened three bottles of beer. The surf frittered along the beach and the wind tugged her hair. Nathalie threw out her towel and sat down in her bikini. Seth watched her and gingerly lowered himself. As he crouched in the sand in his jeans and grey T-shirt, his heavy boots still laced, Mona became curious to see his body. She rotated him in her head, naked, seeing the long heavy thing and his tight high buttocks. She saw that Nathalie’s body was lain out for him. Mona hadn’t had that sort of youth. Love had come in taut trickles and then gone furling back. Men had come to her in defeat and moved onward. Even her lover, the way he had allowed her to photograph his body, the way he’d stilled before her, she had seen his imminent departure surfacing in his eyes.

Nathalie sat up and waved to her and Mona brought their beers onto the sand.

“Tiens Maman, sit here with us. The sun is so rich!” she exclaimed.

But Mona shook her head then returned to the little porch and drank alone. She watched Nathalie laugh. She saw her small hard breasts and flat stomach, her twitching thighs. Further away she looked at Miguel playing in the sand. Jacob walked down with his bucket and spade and helped the child dig. Other village kids raced up to the fair European to try to snatch his toys. They were dressed in rags with amulets around their necks to ward off the deadly spirits prowling the village. Jacob chased away their red furry heads.

After a while Nathalie trod back to the hut, sand stinging her feet. She tied on her sarong. She put sunblock on her arms and turned to Mona to smooth it into her back. Seth watched mother and daughter on the porch. He looked expectant. Mona felt a slither in her gut.

“We’re going for a walk to the point, Maman. Seth wants me to show him what’s on the other side and maybe take some shots. You’ll watch his car, won’t you? He says he has his camera stuff inside.”

Mona watched them walk away. When they were far enough, almost hidden behind a ledge, Mona saw their bodies hook together and share a probing kiss. Mona’s eyesight was excellent.

*

Over an hour passed. Miguel and Jacob came back to the shade. Miguel was hungry. In the meantime Mona had bought baby barracuda from a pregnant girl with an aluminium basin on her head. To lower the tin the girl bent perfectly at the waist, her spine thrust straight out as the cumbersome belly dropped downward. Mona had seen this action over and over, and each time thought of how she would convey the extending vertebrae and the swaying breasts, the membrane harnessing the curled child. It would be hard to reproduce the kinetic. She too was hungry and had finished her second beer.

Jacob had lit a fire and now the coals were ready for grilling the fish. There they lay on the grey wood pallet with their slit bellies and numb eyes, just degrees away from life. Miguel had helped Jacob. He pushed the serrated knife deep into their slimy pouches, pulling the squidgy stuff out, watching the organs collapse in the sand.

Miguel shouted. Mona saw Jacob take off running. She looked to the point and saw Seth half-carrying, half-supporting her daughter down the rock shelf.”

Mona had begun to worry. The beer had a sour chemical taste. Everything was too warm and the wind had blown a veneer of grit over the table. She walked down to the water’s edge, past the indentation Nathalie had left in the sand. She was wrong to fret. She paddled her feet, wishing she were the type of person to cast herself into the sea with abandon, to roll on the bottom and watch the waves from underneath. She wondered if this Seth were to be trusted, or if they were simply making love on the bed of a rock pool, the sea trailing over them, mouths cupped together.

Miguel shouted. She saw Jacob take off running. She looked to the point and saw Seth half-carrying, half-supporting her daughter down the rock shelf. Nathalie was limping, struggling with a knee, crying. There was blood on her thigh.

Mona gasped and began to run. As her throat dried to dust she had a quick déjà vu, indecipherable, merely an evil flare. Focusing as she ran, she saw that Seth looked as though a horrible poison had travelled through him, and his camera was gone. Mona saw Nathalie throw up on the sand.

Nathalie staggered into her arms, pushing away from Seth. Jacob stood transfixed, Miguel grasping his waist. Mona wanted to shield her son’s eyes, wanted to censor another image burnt into his memory, the day my sister was attacked on the rocks. Mona couldn’t look at her fully. The soiled body, the sarong sticking to the blood, the wet shapes of her thighs. Mona wanted to scream at Seth. Broken sounds fell from her mouth.

She held Nathalie close. “What happened to you? Who did this?” She smelt the acid in Nathalie’s sweat, saw there was a small cut on the side of her neck. “Oh my baby!” she cried. “Can you hear me?”

She began pulling Nathalie along. Nathalie sobbed with each step. Miguel held fast onto Jacob, who said something about the police. Seth strode along with them hard-faced and wordless.

When they reached the hut Seth dissolved. He climbed into his car and covered his face with his hands. Then he manoeuvred past Mona’s car and drove off.

Mona ignored this and sat Nathalie in the rattan chair on the porch. She covered her scratched shoulders with a towel. Nathalie shook as the tears dried on her face. Jacob smothered the fire and began to pack their things.

“Miguel, help Jacob put the things in the car,” Mona said. “I’m taking you to the hospital.”

“No.”

“Just tell me what happened.”

“Doesn’t that seem rather obvious?” Nathalie said, turning on her. It wasn’t the first time.

“Did he hurt you? Why didn’t Seth do anything, for God’s sake?”

“Oh shut up, Mona. Just shut up.”

*

Mona had had her first exhibition at the French Cultural Centre a month ago. Nathalie, filming a documentary in Berlin, had been unable to come. Mona had sold three etchings which a friend of hers framed. Two paintings were bought for inclusion at the Nungua Gallery, where a good deal of international tourists passed. Mona had received her first payments ever for her artwork. After so many dark years, it was a triumph.

But the image she adored most had to leave her. It had been inspired by her lover, just before he had disappeared. One night Mona had taken out her camera. She began to photograph his body against the cool bathroom tiles, which was where they made love as Miguel slept. The canvas she had painted afterwards showed a man on hands and knees pretending to prowl, his spine hanging low between his rump and high shoulders, the genitals concealed. Not prey, not a hunter, but a harrowed mythic creature. When her lover left her soon after she finished, she knew the painting belonged to neither of them.

Mona drove past the gallery on their way to the clinic. Nathalie had agreed to see Mona’s gynaecologist, an older Ivorian woman who ran a clinic on the outskirts of town. The doctor cleaned Nathalie’s wounds, took a swab and blood sample, while Mona listened to her daughter release weak cries. Mona felt dizzy. When they were small she had wanted to absorb their pain, to steal their fevers into her own skin. But this, the idea of wanting it was ghastly.

“Have you gone to the police?” the doctor enquired.

“Well, no. My daughter didn’t wish to.”

“Why on earth not? You don’t think this is a crime? Were there any witnesses?”

There was Seth.

Nathalie called out from behind the screen. “I’m not going to the police.”

“Well, I recommend you think about this happening to someone else. Some other woman like yourself. It makes for a very unpleasant experience.”

They drove home through the traffic, Nathalie staring ahead. Mona had left Miguel at a friend’s for a few days, without saying why. It was beginning to feel as though she had brought this on, the walk with Seth to the point, the sickly kiss. Is that what Nathalie was thinking?

“I’ll take you home then. Maybe you should get some rest.

But she knew Nathalie would not. She knew the man’s smell would be there, the prick of the knife, the shocking organ steady.

“I’ll make you a good cup of tea.”

They paced up the damp stairwell. Mona stumbled on the steps, grazed an elbow on the concrete wall, regained her balance. Up on the rooftop the evening wind channelled through the rooms. Nathalie walked directly out to the terrace and for a moment Mona worried she would cast her body over the rail. But she lowered herself onto a chair. She moved with pain, clutching her abdomen.

“Would you like a cover?”

Nathalie didn’t answer. Mona brought out an old silky piece of kente cloth with rippling blues and golds. She tucked it around her. In the kitchen Mona prepared green tea and pulled down two cups. These actions made her feel useful again, as though a healing could begin. She thought of her art, she thought of Nathalie’s love of her craft. They were strong women, they would overcome this awful day. Mona brought out tea.

But outside Nathalie looked so much older. The lines Mona had never noticed on her face had become grave and hard. Her eyelids were fallen, discoloured furrows below them, and the cheeks were those of a gaunt woman whose good health had been stolen. Mona was silent. Everything had been taken from them. This was the day that would never pass.

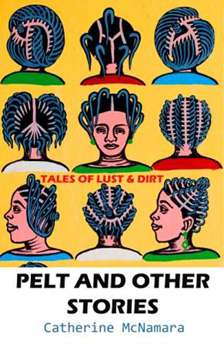

Catherine McNamara grew up in Sydney and has lived in France, Belgium, Somalia and Ghana. She now lives in Italy. Her stories have appeared in Wasafiri, A Tale of Three Cities, Tears in the Fence and the Virago collection Wild Cards. Pelt and Other Stories, a semi-finalist in the Hudson Prize, is published by Indigo Dreams. Read more.

Catherine McNamara grew up in Sydney and has lived in France, Belgium, Somalia and Ghana. She now lives in Italy. Her stories have appeared in Wasafiri, A Tale of Three Cities, Tears in the Fence and the Virago collection Wild Cards. Pelt and Other Stories, a semi-finalist in the Hudson Prize, is published by Indigo Dreams. Read more.