Never happier

by Nicky Harman When I first came across Jia Pingwa’s Gaoxing (高兴: Happy) in 2007, I felt an immediate empathy with this handful of migrant workers collecting the trash of a sprawling Chinese metropolis, and being treated like trash too.

When I first came across Jia Pingwa’s Gaoxing (高兴: Happy) in 2007, I felt an immediate empathy with this handful of migrant workers collecting the trash of a sprawling Chinese metropolis, and being treated like trash too.

In the novel, now published as Happy Dreams, Happy Liu and his fellow villager Wufu arrive in Xi’an to make money, finding a semi-derelict building to live in and settling into life as trash collectors. We follow them through a series of tragi-comic adventures, but when Happy falls in love, things get more serious: the woman, a prostitute in one of Xi’an’s ‘hair and beauty salons’, is arrested by the Vice Squad and sent to a rehabilitation centre; Happy and Wufu get work on a building site to earn the money to bail her out; Wufu dies and Happy tries to take his corpse back to their village. (This is not a plot spoiler, the scene actually opens the novel.)

It is an apparently simple story with some engaging protagonists, especially the eponymous Happy. All the same, I felt a little daunted as I launched into the translation. First and foremost, I had to understand the dialect – I mean really understand it, not just well enough to read and enjoy the novel. Then there is the fact that most of the story consists of Happy’s interior monologue or dialogue. Chit-chat is by its nature allusive, even elliptical. Add dialect to the mix and there are plentiful opportunities for the translator to get the wrong end of the stick. Jia Pingwa is particularly inventive with expressions and images which may be quite local or just his own. When Happy Liu decides to buy an exorbitantly-priced ticket for a theme park, he says: “Of course I knew that money didn’t grow on trees, but once we’d gotten that far [in the ticket queue], it was like a toad propping up a table; you had to just grin and bear it.” And elsewhere his friend Wufu insists he’s going to get drunk today, because, “After all, tomorrow my gob might be sewn shut!” And that’s my gloss on a much more obscure expression: 哪怕明日嘴吊起来哩!, “Tomorrow I may be strung up by my mouth [like a fish on a hook].”

Dialogue is the most difficult thing to translate, doubly so when it contains large amounts of slang. I had to give Happy Liu a believable, but not too local, voice, one that inhabited a sort of middle ground of spoken language.”

The larger challenge was, I felt, getting a convincing voice for Happy Liu in English. I wanted to get over the flavour of his speech but I knew I had to use ‘standard’ English, even if it did include a lot of slang. If I had tried to translate dialect with an English-language equivalent, if I had made Happy Liu sound like, say, a Glaswegian binman, it would have made him literally incredible to the reader. I thought about this a couple of weeks ago, watching a performance of Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing set in Zapatista Mexico. The words were Shakespeare, the setting a different time and a different place, but the drama worked. In Happy Dreams, the equivalent transformation was in the language. Dialogue is the most difficult thing to translate, doubly so when it contains large amounts of slang. I had to give Happy a believable, but not too local, voice, one that inhabited a sort of middle ground of spoken language. This was particularly so because the book publisher is American. I write British English but a number of my go-to ‘Britishisms’ which conveyed (to me, at least) the emotional tenor that I was hearing in the Chinese had to be ditched at the editing stage. I don’t write American slang, it’s not my language, so I needed the editor’s help to find American-sounding substitutes. Fortunately, she was both sensitive and sympathetic, and the whole process was rewarding, if at times challenging, as I tested every edit against that inner voice I had so carefully constructed. For instance, Happy says: 我们…快快活活每人多赚了五百元钱. My version went: “We’d been really chuffed to earn an extra five hundred yuan each.” ‘Chuffed’ represents the adjective 快活 (kuai huo: happy, cheerful). Repeating the characters as Jia does, 快快活活, kuai kuai huo huo, gives the adjective an intimate ring, rather like the way Latin American Spanish adds a diminutive to an adjective, making ‘despacio’ (slow) into ‘despacito’. But ‘chuffed’, which also has an intimate feel, was too British. In the end, I was happy with the edit “pleased as punch” and, hey, translation is after all the art of negotiation and compromise.

But ‘decoding’ the novel and re-encoding it in English was far from laborious, and there were many entertaining moments. Jia Pingwa says that his characters’ names are integral to the layers of imagery he builds up in the story. So in Happy Dreams, one of the trash collectors is Huang Ba. His surname is Huang, his given name Ba, meaning ‘eight’, as in eighth child in the family. But any Chinese reader will immediately chuckle because Huang Ba sounds like Wang Ba, a term of abuse so common nowadays that it even appears in urbandictionary.com. I failed to reproduce that pun at all convincingly but I did come up with another punning name that I was quite pleased with. One of the workers is called Zhu (朱), a common surname that also means cinnabar or vermilion. His mates rudely call him Zhong Zhu (种猪: pig), alluding to his allegedly large balls, because he’s the only one who has a woman living with him and the other men suffer agonies of jealousy and frustration. So I diverged from my normal practice of leaving surnames exactly as they are, and created a new surname for him. Instead of Mr Zhu, he became Mr Gules (‘gules’ is a vermilion colour in heraldry) and his nickname was then Goolies. I played around with many alternatives, and brainstormed it with fellow translators, but that one stuck.

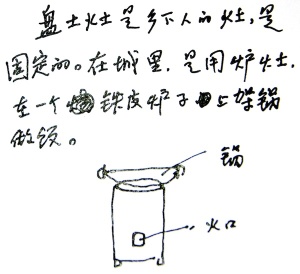

In translating Happy Dreams, I had to mentally inhabit a very unfamiliar world, the city of Xi’an and its sprawling slummy outskirts, so I did a lot of web searching on buildings, furniture and street food. However it is an unfortunate fact that the more humble the people being described, the less likely it is that you will find photographs of their homes and possessions online. (The exception to that being pictures posted by horrified travellers of maggot-infested latrines.) The cooker Happy and Wufu used had me scratching my head for a long time. 土灶 is any kind of cooker or fire pit, once upon a time made of mud-bricks, 土, but this one was moveable. What on earth was it made of? Then Jia Pingwa came to my rescue with a hand-drawn sketch. The cooker turned out to be something like an old oil drum, with a hole made in the side for the fuel, and a top opening for the wok to balance on. I smiled when I got that email. It was definitely an “Oh, of course!” moment.

In translating Happy Dreams, I had to mentally inhabit a very unfamiliar world, the city of Xi’an and its sprawling slummy outskirts, so I did a lot of web searching on buildings, furniture and street food. However it is an unfortunate fact that the more humble the people being described, the less likely it is that you will find photographs of their homes and possessions online. (The exception to that being pictures posted by horrified travellers of maggot-infested latrines.) The cooker Happy and Wufu used had me scratching my head for a long time. 土灶 is any kind of cooker or fire pit, once upon a time made of mud-bricks, 土, but this one was moveable. What on earth was it made of? Then Jia Pingwa came to my rescue with a hand-drawn sketch. The cooker turned out to be something like an old oil drum, with a hole made in the side for the fuel, and a top opening for the wok to balance on. I smiled when I got that email. It was definitely an “Oh, of course!” moment.

Happy Liu is an unlikely hero, Chaplinesque, pretentious, engaging, obnoxious, honest, devious, foul-mouthed and tender.”

Appended to the novel is Jia Pingwa’s Afterword, a fascinating and moving essay in which Jia touches on how he did his research, the real Happy Liu who inspired the novel and, more broadly, on the plight of villagers faced with the choice of bleak rural poverty or a labouring job in cities with all the attendant privations and tantalising opportunities. More than that, the Afterword points to the novel’s slightly curious, or rather ambivalent relationship with the real-life Happy. While English-language novels frequently carry an All Persons Fictitious disclaimer, Jia Pingwa details his friendship with Happy Liu, apparently confident the man will be flattered by his literary reincarnation. (Though it is interesting that when he begins his research into other migrant workers’ lives, he is initially rebuffed with the response: “He wants to see us? Like we’re performing monkeys?… If he’s playing the Empress Dowager playing at harvesting the crops, then tell him no.”)

What Jia does not write about is how he created the character of the fictional Happy Liu, perhaps because as a novelist he takes the process for granted. But however authentic Happy Dreams is, it stands or falls as a novel. And while the other characters are somewhat two-dimensional, though none the less entertaining for that, in Liu we have particularly finely drawn character. Happy Liu is an unlikely hero, Chaplinesque, pretentious (he is always ready with an aphorism or a homily), engaging, obnoxious, honest, devious, foul-mouthed and tender – to his best friend and to his lover. There is no happy ending in Happy Dreams, but its hero keeps picking himself up and dreaming on.

Jia Pingwa was born in 1952 in Dihua Village, Danfeng County, Shaanxi Province, and went on to graduate from Northwestern University in Xi’an, where he still lives. Jia stands with Mo Yan and Yu Hua as one of the biggest names in contemporary Chinese literature. His fiction focuses on the lives of common people, and is well known for being unafraid to explore the realm of the sexual. Ruined Capital was banned for many years for that reason, and pirated copies sold on the street for several thousand RMB apiece. Happy Dreams, translated by Nicky Harman, is published in paperback by Amazon Crossing.

Jia Pingwa was born in 1952 in Dihua Village, Danfeng County, Shaanxi Province, and went on to graduate from Northwestern University in Xi’an, where he still lives. Jia stands with Mo Yan and Yu Hua as one of the biggest names in contemporary Chinese literature. His fiction focuses on the lives of common people, and is well known for being unafraid to explore the realm of the sexual. Ruined Capital was banned for many years for that reason, and pirated copies sold on the street for several thousand RMB apiece. Happy Dreams, translated by Nicky Harman, is published in paperback by Amazon Crossing.

Read more

ugly-stone.com

Nicky Harman lives in the UK and is co-Chair of the Translators Association (Society of Authors). She has translated a wide range of Chinese authors of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. She also works on Paper-Republic.org, the website promoting Chinese literature in translation, organises translation-focused events including the China Fiction Book Club (with Helen Wang), mentors new translators and judges competitions. She has contributed to literary magazines such as AsianCha, Chutzpah, and Words Without Borders. She won first prize in the 2013 China International Translation Contest with Jia Pingwa’s short story ‘Backflow River’.

paper-republic.org/nickyharman

@NickyHarman_cn

@cfbcuk

Read an extract from Happy Dreams