Origami

by Kirsty LoganAnother paper cut. Rebecca’s hands were a mess: swollen with tiny cuts, peppered with dry patches. She’d have to make sure they were all healed before Sean got home, or he would know what she’d been doing.

She checked the clock. Almost six: she’d better get some dinner on. She pottered around the flat, checking the front door was locked and deciding which soup to heat.

Sean was supposed to phone tonight. It had been nearly a week, but the phones on the oil rig were always in high demand. Rebecca understood, even though it was a shame that they had such little phone time. At least Sean only did trips of a month: some of the engineers were away for six months at a time. Men with wives, children, pets, and friends they didn’t see for half a year. No wonder there was a mad rush at phone time. The men must be so lonely, stuck in the middle of the sea with no one to love. Weeks of meals for one, falling asleep in front of the TV, watching happy couples in bars and shops and restaurants. Stuck in the middle of the city with no one to –

She was halfway across the living room carpet. She must have been wandering towards the TV, or maybe the bathroom. The cupboard was that way too, but she wasn’t about to make that mistake again.

She hurried over to the cooker and took the soup off the flame, the inside of the pan crusted with blackened chunks. The smell of burning filled her throat.

The pages were forming into fingers. With her thumbnail, she scored lines of knuckles on the paper fingers. She placed them carefully on the coffee table, then started folding some toes.”

At five to eight Rebecca was on the couch trying not to stare at the phone. The pan, bowl and spoon were washed and drying by the sink; the TV tuned to a reality show. She was fiddling with the pages of the TV guide, but only because she was nervous about Sean’s phone call. The pages were forming into fingers. With her thumbnail, she scored lines of knuckles on the paper fingers. She placed them carefully on the coffee table, then started folding some toes. The paper was thin and brightly-coloured, the knuckles creased across faces and times.

She resisted the urge to pick up the phone on the first ring. She carefully arranged the paper digits, then answered on the fourth ring.

Hello? She tried to sound husky, like she was halfway through a cigarette.

Hey, Becks.

Sean, baby. She bit her lip: that was too much. How are you? How’s work going?

In the silence, she heard her muffled words back through the receiver.

It’s good. Busy. Look, Becks, I’ve only got a couple of minutes. He paused, but she didn’t say anything. The delay meant that they’d only end up talking over one another. I’m really sorry, but they want me to stay on for another week. I wouldn’t, you know, but we could use the money. Rebecca listened to the clicking quiet after his words. Becks? You there?

Yes! Yes, I’m here. Sorry, the delay. I thought you weren’t finished.

So it’s okay? About the extra week?

Rebecca swallowed the lump in her throat as she stared at the cupboard door. Of course. You’re right, the money would be nice. But you know – she coughed. I’ll miss you. It’s lonely here without –

Becks, you won’t – They both started talking at the same time, and had to spend a few seconds saying: no, you go.

Becks, it’s just that – I know it’s stupid, but last time – I mean, that – you wouldn’t, right? It’s stupid to ask, but I worry about it…

Rebecca’s cheeks were blazing. Even though Sean couldn’t see her, she did her best innocent smile.

Of course not. Don’t worry, love.

I know. I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have asked. Anyway, that’s my time up so I’d better go. I’ll call the day after tomorrow, same time. And Becks? I miss you.

Rebecca hung up the phone. She collected the paper fingers and toes and walked to the cupboard door. She closed her eyes, held her breath, and opened the door.

Later, halfway to sleep, she was pleased that she’d managed to throw the fingers inside without looking. Looking would lead to touching, which would lead to bringing him out of the cupboard, which would mean he’d be in the bed now. But it was just her, so she’d won. She wasn’t lonely, she was victorious.

Rebecca woke from origami dreams, familiar shapes folding into strange forms. Eyes still sleep-glued, she ran her hands through her hair, feeling something hard and rough against her forehead.

Clenched in her palm was a crumpled paper hand.

Her whole body jerked. She threw the paper hand across the room, watched it sail through the air. It seemed to wave at her as it went, then lay silently unfolding on the carpet. She lifted the duvet, scanning the warm darkness for foreign body-parts. There was nothing but her own pale legs.

When her heart had slowed to a normal pace, Rebecca got up. She dressed without looking at the hand.

By the end of the day, Rebecca was exhausted. Avoiding paper might be feasible for a builder, or a sculptor, or a bartender; for a legal secretary it was impossible.

Much of her work was done on computer, so she’d thought she could manage; but she’d forgotten about the memos, Post-its and phone messages that snowed onto her desk throughout the day. By mid-morning, her wastepaper bin was full of crumpled body parts.

She’d tried to clear all the paper out of the house, but there was just so much of it: newspapers, novels, receipts, wrappers, bills, magazines. Different colours, weights, textures, patterns.”

But working hours weren’t the only problem. During her lunch break, she paused mid-sandwich to fold intestines from her newspaper. Walking out of the office, her nervous fingers made an ear out of the tissue in her pocket – luckily the thin sheets wouldn’t hold the shape, and unfurled as she threw it on the pavement. On the journey home, her bus ticket became a tongue.

When the bus reached her stop, she tore up the tongue and stuffed it down the seat. She kept her fists clenched as she walked home.

Rebecca was watching the news with her hands held between the sofa cushions. She’d tried to clear all the paper out of the house, but there was just so much of it: newspapers, novels, receipts, wrappers, bills, magazines. Different colours, weights, textures, patterns. Magazine pages were eyeballs: colourful, and held a shape well. Broadsheets were limbs: large enough for a whole leg. The TV guide had already become a pair of kidneys, and it wasn’t safe to let her hands roam anymore.

Rebecca jumped when the phone rang, but she sat still until the fourth ring.

Hello?

Becky, hi. How are you?

Yeah, you know. Keeping busy.

Good. I’m sorry I couldn’t call earlier. I queued for the phones every night, but I had to give up or I’d have missed my sleep.

That’s okay. You’ll be home soon, and then we can talk any time we want.

Rebecca listened to her muffled echo in the receiver, then the crackling quiet. She opened her mouth to speak

Becks, about that. They offered me another week. You know you were unhappy with me missing New Year, and with the new shift pattern I’ll be home right into the start of January. So it’s better really, right? Becks? Rebecca?

Rebecca stepped back from the cupboard door. She was already at the full reach of the phone cord; to open the cupboard, she’d have to put down the phone.

I’m here, Sean. And it’s fine. I’m glad you’ll be here for New Year.

God, Becks, I’m so glad. You’re not feeling…

Lonely, thought Rebecca. Lonely lonely lonely.

No, not at all. I’m actually going out with Jen tonight, so don’t worry.

That’s good. I put your photo beside my bed so I see you last thing at night and first thing in the morning. Your photo isn’t very chatty though. I miss saying good morning and hearing you say it back. But look, I have to go, the phone queues are huge tonight and everyone’s giving me the evil eye.

Okay. I love you.

Love you too.

Rebecca waited for the dial tone, then placed the phone at her feet. She smoothed down her skirt, neatened her hair, and opened the cupboard door.

The man inside had paper hands, paper legs, paper lungs. He had eyeballs, toenails, a paper heart. He was missing some bits – spleen, eyebrows, a left heel – but that didn’t matter.

Rebecca helped him out of the cupboard, arranging him carefully on the couch. She flipped to the channel she knew he liked, and settled down beneath his arm. She nuzzled his cheek and stroked his broad, creased chest.

He was incomplete, imperfect. But he was here.

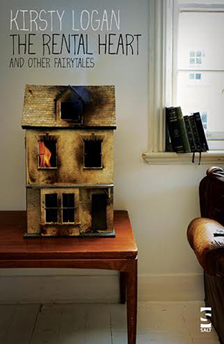

From the collection The Rental Heart and Other Fairytales, published by Salt Publishing. Read more.

Kirsty Logan is an award-winning writer based in Scotland. Her fiction has been published in literary magazines and anthologies all over the world, broadcast on BBC Radio 4, displayed in galleries, and translated into French, Japanese and Spanish. Kirsty has received fellowships from Hawthornden Castle and Brownsbank Cottage, and was the first writer-in-residence at West Dean College. She has previously worked as a bookseller, and is now a literary editor and freelance writer.

Kirsty Logan is an award-winning writer based in Scotland. Her fiction has been published in literary magazines and anthologies all over the world, broadcast on BBC Radio 4, displayed in galleries, and translated into French, Japanese and Spanish. Kirsty has received fellowships from Hawthornden Castle and Brownsbank Cottage, and was the first writer-in-residence at West Dean College. She has previously worked as a bookseller, and is now a literary editor and freelance writer.

kirstylogan.com

Follow Kirsty on Twitter: @kirstylogan

Author portrait © MonkeyTwizzle