The sins of our future

by Mika Provata-CarloneMany years ago, a young boy from an affluent Egyptian family was travelling with his parents by train to their summer house somewhere deep down the valley of the River Nile. This was a journey he had made many times as he grew older. Each time, the curtains of their first-class carriage were pulled tightly together, so that the passengers inside might not be unnecessarily unsettled by the sight of slums and rugged local fellahin, by the filth, deprivation and offending aesthetics of the other side of existence. The train functioned as a clinical sanitiser of conscience: what the eye could not see, the heart need not be troubled by. On one of those journeys, the boy pushed the curtains aside, keen to look outside. And what he saw, he tells in a later book, forever changed his life, his mind, the way he felt he could, and should belong to the world. His name was Hassan Fathy, and he would become one of the most extraordinary and groundbreaking architects of the 20th century. He would pioneer design and techniques that were startlingly innovative in that they resurrected the wisdom of old stones, of people and traditional methods. He worked with some of the most cutting-edge, modernist practitioners of his art, with that single aim: to produce an architecture that would house the here and now as well as the future, following the teachings (and avoiding the pitfalls) of the past, and of each particular local tradition. Progress for Fathy was impossible if it did not include the motion of return, the gesture of including all that had been there before. What Hwang Sok-yong calls in his novel At Dusk, “everyday life in its tenacious continuity.”

Like Fathy, Hwang wants to change the world in an uncompromising, daring way. He too possesses the poise, polish and wisdom of a scholar, perhaps even of a patrician, as he speaks intimately about things that are as visceral and troubling as the images and scenes of human life that were carefully blotted out of memory and awareness for Fathy’s family during their summer journeys. At Dusk explores our relationship with what we seek and with what we feel the urge to escape. It delves into the question of design, intent, the principles of art and technology, and their effects on the shape and form, content and essence we give to our lives.

At Dusk is the story of an architect who was part of what South Koreans call their miracle, the rebirth of their economy, material infrastructure and urban universe. Park Minwoo, the architect, has helped transform both the image and the human element of his country. Nearing now the dusk of his own life, we see him as though travelling back in time, with the curtains fully drawn apart, and looking at the slums he thought he had left behind, eradicated with his blueprints, structures and new aesthetics. Like Fathy, he is confronted with the choice of a revelation: the ineffable, irreplaceable, now tragically lost vital substance that those “material non-entities” actually contained in their roughness, inadequacy and objectionable claim to a future.

Hwang has a knack of presenting us with stories that look like the simple jottings of an idle, curious man, as he lets his eye wander over his fellow human beings. Yet each phrase almost is invested with the power of a parable.”

Structured as a dynamic triptych of three panels that have been severed and are now forced to lead separate existences, of three voices, perspectives, narratives, that are moving slowly towards a reconstruction of an original image that is desperately yearned for and at the same time impossible, At Dusk has Hwang’s customary blend of fragility and brutality, of tenderness and raw pain. The architect’s very precise, pictorial discourse, with its understanding of structure and connections, a reverence for new lines and old complex sketches, the design of life and its solid unpredictability, interweaves with the narrative of failed promises, of ties that can bind one to heaven and earth as well as suffocate, and with the already lost speech of a younger generation that seeks to look beyond materiality, to a spiritual centre that has become inaccessible, even unavailable.

Edge House, a private residence in Pangyo, Seoul designed by Joongwon Lee and Kyung-A Lee/iSM-Architects, photographed by Hyosook Chin, 2014. Wikimedia Commons

Each of these characters, voices, angles of vision and states of being subsists on a plane of desperate enquiry, as they pursue the question of the impermanence of monuments to memory and the eternity of the most ephemeral of human castles in the air. “Is there really any humanity in architecture?” the novel asks, and by architecture it means “buildings made of space, time and humanity”, but also “money and power”, cities that replace ancestral wretchedness with a polish that has forgotten to include the human, failing element. Roots, tradition, new starts and hopes, buildings cleansed of the memory of trauma, deprivation and adversity, rising on the unhealed stumps of wounds that will not be forgotten. Quite the opposite of Fathy’s architecture for the people, where pain and what was little were meant to become strength and the potential for all that could be.

“It [is] hard to fall asleep in a new place,” remarks Park Minwoo as he oscillates between past and present. Perhaps human beings need the attachment of what has been, even in order to attain the state beyond what should not be… Hwang has a knack of presenting us with stories that look like the simple jottings of an idle, curious man, as he lets his eye wander over his fellow human beings. Yet each phrase almost is invested with the power of a parable and the unmistakable urgency of a philosophical critique into the state of our society.

In this sense, At Dusk is an ironic title reflecting on South Korea’s golden dawn: how do you initiate a country into a new modernity, the novel seems to ask, to a Western version of its own tradition? How can you keep people’s souls safe while delivering that much longed-for manna (or emperor’s new clothes) called progress, prosperity, advancement? “You know what the Buddha said. The wheel of life takes a hundred years to turn. Which means that none of us make it all the way around before we have to get off.” How then do you venture forward without burning the bridges that can guide you back? The architect cannot escape his duty in the face of the future and the past, in the face of innocence and sin. “Everyone thinks it’s good to be an architect, because your buildings will stand long after you are gone, but for all you know, they could be left looking greedy and ugly.”

The story of the architect, his childhood sweetheart and the girl who dreams to be a dramaturge as she works the graveyard shift at a warehouse, are all full of the rancid, stale smell of lives that have fallen off the normal grid of things. There is cruelty and slovenliness, just as in the denied landscapes of urban decay Fathy felt the urge to look at, yet there is never bitterness, resentment, envy or even anger in Hwang’s impression of our defective universe. His is an unwavering, deeply human perspective of what the world is, could be and should be. Grit and bare violence, the depraved and the abnormal are looked at with the sadness of those who try to hope for more, rather than the rancour of those who define themselves as the world’s dispossessed. Time and time again, Hwang allows for the deeper humanity of tragedy to stand out, and these would be vignettes were it not for their subject matter. In their current form, they have the power of Capra’s photographs, with a unifying, running commentary weaving the threads into a densely textured fabric: an architect’s life, architecture vs. chaos, master building vs. mass devastation. They are almost a series of vanitas tableaux, pitting material affluence and the race for success against the life of fulfilment: the difference, we are told, between poverty and wealth, is mere cynicism, otherwise “everyone was [just as] anxious and lonely.”

At Dusk is a journey through memory and through the necessary potential and duty of architecture; through human spaces and urban topographies of existence and non-being.”

Hahoe Folk Village, Andong, South Korea, preserving architecture and traditions from the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897). Julie Facine/Wikimedia Commons

Hwang asks time and time again: at the dusk of old hierarchies, orders and structures, is it really possible to transcend, let alone eradicate, class and cultural distinctions? Can we create a society of real coherence, empathy and connectedness? Or is all a mirage, a precarious, postmodernist architectural concept, with no structural understanding of the social re-engineering skills that would be required to achieve an imperfect, yet viable equilibrium? What is the price of prosperity? “Architecture is not the destruction of memory, it is the delicate restructuring of people’s lives on top of a sketch of those memories. We have already failed horribly at achieving that dream.” It is a dire reflection, yet also one that resonates with the promise of an alternative plenitude of meaning. Park Minwoo has failed, in his architecture and his life, to recognise the essential elements of both form and content, of vital structure. Yet he has written a book, The Architecture of Emptiness and Fullness, that contains the wisdom he was unable to apply himself.

Like architecture, memory and life are based on the evanescence of permanence, on structural principles, projections and perspectives. On cross-sections and whole, fish-eye diagrams. At Dusk is a journey through memory and through the necessary potential and duty of architecture; through human spaces and urban topographies of existence and non-being. For Korea, this is a novel that should mark a turning point in its sense of identity; for non-Korean readers, it is a blueprint of the critical elenchus we need to undertake before it is tragically far too late for all our local traditions, cultures and individual lives.

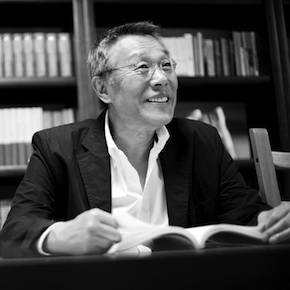

Hwang Sok-yong was born in 1943 and is arguably Korea’s most renowned author. In 1993, he was sentenced to seven years in prison for an unauthorised trip to the North to promote exchange between artists in the two Koreas. Five years later, he was released on a special pardon by the new president. The recipient of Korea’s highest literary prizes, he has been shortlisted for the Prix Femina Etranger and was awarded the 2018 Emile Guimet Prize for Asian Literature for At Dusk. His previous novels include The Ancient Garden, The Story of Mister Han, The Guest, The Shadow of Arms and Familiar Things. At Dusk, translated by Sora Kim-Russell, is published in paperback and eBook by Scribe.

Hwang Sok-yong was born in 1943 and is arguably Korea’s most renowned author. In 1993, he was sentenced to seven years in prison for an unauthorised trip to the North to promote exchange between artists in the two Koreas. Five years later, he was released on a special pardon by the new president. The recipient of Korea’s highest literary prizes, he has been shortlisted for the Prix Femina Etranger and was awarded the 2018 Emile Guimet Prize for Asian Literature for At Dusk. His previous novels include The Ancient Garden, The Story of Mister Han, The Guest, The Shadow of Arms and Familiar Things. At Dusk, translated by Sora Kim-Russell, is published in paperback and eBook by Scribe.

Read more

Author portrait © Philippe Lissac

Sora Kim-Russell is a poet and translator, originally from California and now living in Seoul, where she teaches at Ewha Womans University.

@spacenakji

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.