The tricycle man

by Harriet LaneI arrived at boarding school in England a few weeks short of my twelfth birthday. I’d spent my childhood switching friends, schools, houses, countries, continents (my father was a diplomat) and at some point all this had begun to pall. I wanted things to stay the same: the same faces every term, the same rooms in the same buildings, the same sequence of seasons, year in, year out. Nothing seemed more exotic or appealing than things not changing.

I thought I was signing up for midnight feasts and anchovy toast, lacrosse matches and pranking Mam’selle – all that jazz. Of course the reality was quite different. This was a progressive co-ed school, a place where you could make bread and build barns, where the teachers were addressed by their first names; but at the most immediate level ‘progressive’ meant that the pupils, freed from the tyranny of one kind of uniform, simply invested in another. I arrived an old-fashioned sort of child in a kilt and Clark’s lace-ups, but by bedtime I knew these things would not do and would always be held against me. It was all painfully evident: I was in the wrong demographic.

My classmates, on the whole, were not children; they were kids, sophisticated beings who wore stretch jeans and Converse, who listened to Soft Cell and the Stray Cats, who hooked up with other kids and snogged them in the queue for Sunday evening hot chocolate. Kids who (of course) were a bit lost themselves, secretly puzzling over what they were doing here when home was only an hour or so away, in Chelsea or Surrey or Oxfordshire.

At least I knew why I was there. At least my parents lived on the other side of the world.

In this alien landscape the kids were giants and most of the Middle School staff were pygmies: mainly benign, but detached, rather remote, even though we knew them by their first names. (You wouldn’t take your worries to them any more than you’d put your worries down in the weekly letter to your parents — who might, after all, be worried by it.) Possibly the teachers had a sentimental view of the pupils and felt we should be trusted to get on with things, not quite imagining what ‘things’ we might be up to. Or maybe they weren’t that bothered.

The grown-up who made a difference was Alastair, my first English teacher: a charming, easygoing person with wavy red hair and dimples and a jolly laugh, like an overgrown cherub. Alastair – who I believe played both the double bass and the bass recorder – favoured plus-fours, thick woollen stockings and sometimes a monocle, and arrived in the mornings (he had his own young family and lived nearby) on – oh my God, can this be true? – a man-sized tricycle.

Mainly I remember the atmosphere of those classes, the sense of excitement and possibility as a new world opened up for me, a world where I could be free and unselfconscious”

Soon I knew to look forward to Alastair’s lessons and the anxious, hopeful moment when he handed back our essays (his gorgeous calligraphy, the bold sweeping As that made a dismal Thursday spectacular). I seem to remember A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Edward Thomas and Thomas Hardy, but mainly I remember the atmosphere of those classes, the sense of excitement and possibility as a new world opened up for me, a world where I could be free and unselfconscious (unlike the world of school).

Perhaps it’s not so peculiar that two of the things he taught me came back very powerfully many years later when I started writing fiction.

The first gift Alastair gave me was a lesson on haikus. I still remember the shock of it: somehow in a mere seventeen syllables, a mere three lines, a simple description (a tree in blossom, a breeze on a body of water) could create a mood, an atmosphere, without any emotion being directly articulated. It struck me as a sort of magic. Concision and precision; elegance; restraint; a sense of something mysterious happening beyond the words themselves.

Modern upright tricycle. ‘TRIKER’/Wikimedia Commons

It was only one class, maybe two. A couple of afternoons in a prefab classroom, condensation on the windows, a view of the car park. But I kept thinking back to that lesson and what I’d learned in it while I wrote my first novel, Alys, Always, a first-person narrative that depends on the reader absorbing the detail, picking up on inferences, reading between the lines. Understanding that there’s more to the story than the words on the surface.

Alastair’s second gift was a weekly assignment called ‘Observations’. One sheet of paper, more if we could manage it, to describe any kind of mundane activity: making toast, for instance, or getting dressed, or drinking a glass of water. Most of my classmates hated Observations (so boring!) but I loved them. I loved the discipline: the accumulation of detail and the curious heady pleasure of finding exactly the right word, the only word that would fit, like a key in a lock. And then there was the satisfaction of capturing something so fleeting and tiny and insignificant that you’d never really noticed it before.

Alastair was asking us to look for the extraordinary in the ordinary, to notice the hidden texture of everyday life. I only fully understood the value of this when I wrote Alys, Always and found myself reminded of the scratch of those cheap blue plastic fountain pens handed out at the stationery cupboard, the navy ink sputtering onto the page, the joy of recognising the truth in something you’d written: yes, yes, that’s how it is. Just like that.

And, just as valuable: Slow it down. Look close.

Alastair sent me a kind message after he’d read Alys, Always (all of my English teachers did, and it’s strange how much their approval still means to me: it was always English that kept me going, I can’t imagine how I’d have coped with adolescence otherwise), and then he came to lunch with two good friends from school, people I used to sit next to in his class, plus assorted husbands and children. Over lunch I told Alastair about the Observations echoing back to me and somehow informing my writing all these years later, and he said he had wondered about that when he read the book. I think he was pleased; and I was, too.

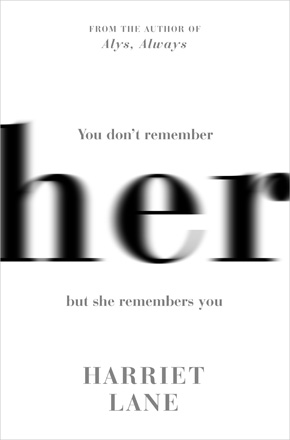

Harriet Lane’s debut Alys, Always was a You Book Club choice, longlisted for the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award and shortlisted for the Writers’ Guild Best Fiction Book award. She lives in north London with her husband and two children. Her is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in hardback, eBook and downloadable audio. Read more.

Harriet Lane’s debut Alys, Always was a You Book Club choice, longlisted for the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award and shortlisted for the Writers’ Guild Best Fiction Book award. She lives in north London with her husband and two children. Her is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in hardback, eBook and downloadable audio. Read more.

harrietlane.co.uk