The untelling

by Claire FullerThe early morning light filters through the empty bottles which clutter our caravan’s kitchen table. The light stains my nightdress with blotches of blue, green and red, and I lean over the back of a chair, waiting, breathing. The chair is a cast-off from Gil’s mother, and I see that on the vinyl seat there is a pattern of hay bales, seed pods, and ripe fruit, tumbling over each other in an abundance of harvest time. As I exhale, I remember the previous evening.

Gil had whooped and jumped, shaking the caravan’s shabby structure. “A celebratory drink!” he cried, grabbing my coat, stuffing me into it. And while I calculated the price of a whiskey and a small lemonade, he was already drunk on happiness. “You worry too much about money, Ingrid,” he said. “I’ll get us a drink,” and he winked. Then he waltzed me up the lane to the pub.

“Wait,” I said when we were standing on the threshold. “You have to promise not to tell anyone. Not yet.”

He put his hands on my cheeks, bent down and kissed me full on the mouth. “God, I love you,” he whispered, opened the door and we plunged headlong into the yellow light, floral carpet, smoke, beer and noise of The Rising Sun.

It was a Saturday night and the pub was full: tweedy farmers with their weather-polished cheeks; Mrs Passerini, with her yellow fingers, fur coat and plimsolls, perched on her usual stool…”

Gil pushed through the crowd, shaking a few hands as he passed, and I followed behind in the passageway he made. When he reached the bar he chinked a teaspoon against an empty glass. It was a Saturday night and the pub was full: tweedy farmers with their weather-polished cheeks; Mrs Passerini, with her yellow fingers, fur coat and plimsolls, perched on her usual stool; the owner of the big house and his grown-up sons buzzing like flies around the Spencer sisters, who waved their spidery eyelashes; the aged Mackies; the newly-married Aspinalls; the Sims; the Harbords; and Martin and Sally serving drinks.

Chink, chink, chink, went Gil’s spoon. And the room quietened.

“Friends and neighbours,” he said. “I have an announcement.” He put his arm around me. “That is to say, Ingrid and I have an announcement. My lovely wife is…”

“Up the duff,” shouted Ed Walker.

“Knocked up,” called another joker.

Gil gave a slow nod. “Indeed,” he said. “Together, Ingrid and I are riding the baby train.”

Gil didn’t have to buy any drinks that night. And when the pub closed, the people and the bottles came back to the caravan. So many glasses raised, so many congratulations, so much money spent.

Now, as another cramp grips me, I think about all the untelling I will have to do, starting with the sleeping Gil, and I decide to let him stay happy for another half hour. Then I think about the untelling of our friends and neighbours, and what they will say, and whether they will even believe that yesterday we were on that train, and that today it has left the station without us.

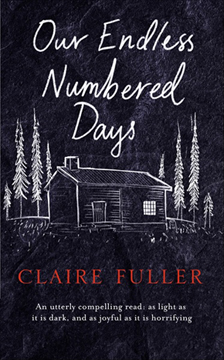

Claire Fuller is a novelist and short fiction writer. For her first degree she studied sculpture at Winchester School of Art, specialising in wood and stone carving. She began writing fiction at the age of 40, after many years working as a co-director of a marketing agency, and has a Masters in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Winchester. Her first novel, Our Endless Numbered Days is published in the UK in February 2015 by Fig Tree, and in the US in March by Tin House.

Claire Fuller is a novelist and short fiction writer. For her first degree she studied sculpture at Winchester School of Art, specialising in wood and stone carving. She began writing fiction at the age of 40, after many years working as a co-director of a marketing agency, and has a Masters in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Winchester. Her first novel, Our Endless Numbered Days is published in the UK in February 2015 by Fig Tree, and in the US in March by Tin House.

clairefuller.co.uk

@ClaireFuller2