The year of the Watchman

by Lucy Scholes As 2015 draws to a close it’s time to reflect on the literary highlights of the past twelve months. I ended last year’s round-up with brief mentions of a few titles I already had my eye on, and I’m pleased to say that the vast majority of them didn’t disappoint. Edith Pearlman’s short-story collection Honeydew (John Murray); debut novels in the form of Miranda July’s The First Bad Man (Fourth Estate), Jill Alexandra Essbaum’s Hausfrau (Mantle), and Elisa Albert’s After Birth (Chatto & Windus); and new novels from seasoned pros Sarah Hall with The Wolf Border (Faber), Lawrence Osborne with Hunters in the Dark (Hogarth), and Jonathan Franzen with Purity (Fourth Estate). I had high hopes for all of these and each one exceeded my expectations.

As 2015 draws to a close it’s time to reflect on the literary highlights of the past twelve months. I ended last year’s round-up with brief mentions of a few titles I already had my eye on, and I’m pleased to say that the vast majority of them didn’t disappoint. Edith Pearlman’s short-story collection Honeydew (John Murray); debut novels in the form of Miranda July’s The First Bad Man (Fourth Estate), Jill Alexandra Essbaum’s Hausfrau (Mantle), and Elisa Albert’s After Birth (Chatto & Windus); and new novels from seasoned pros Sarah Hall with The Wolf Border (Faber), Lawrence Osborne with Hunters in the Dark (Hogarth), and Jonathan Franzen with Purity (Fourth Estate). I had high hopes for all of these and each one exceeded my expectations.

Honeydew is 78-year-old American Pearlman’s second collection to be published in the UK, though the stories were chosen from a back catalogue of forty-odd years of writing. Centred on the fictional Boston suburb of Godolphin, some have an aptly Cheeverish taste – a flat-chested woman with overlapping front teeth: “no boobs, too aristocratic for orthodontia” – but there’s nothing insular about the world Pearlman depicts. One story is about a circumcised woman from an unnamed African country, while another features a Jewish family from Jerusalem.

Other standout collections were Lauren Holmes’s Barbara the Slut and Other People (Fourth Estate), Diane Cook’s Man v. Nature (Oneworld), Thomas Morris’s We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber), and past Pulitzer Prize winner Adam Johnson’s Fortune Smiles (Doubleday). Holmes brought the minefield of adolescence and one’s twenties to animated life, from high-school slut shaming and the messy politics of female friendships to lost twenty-somethings trying to work out what the hell to do with their lives.

Cook, meanwhile, took allegory to the next level in her strange unsettling tales – 9/11 is turned into office workers fleeing for their lives from a bloodthirsty beast slowly ascending their high-rise building; the fears of early motherhood manifest in an actual kidnapper lurking on the front lawn of a suburban home; and, faintly reminiscent of the set-up in Yorgos Lanthimos’s recent film The Lobster, widows and widowers are confined to segregated state facilities until they pair off again.

Cook, meanwhile, took allegory to the next level in her strange unsettling tales – 9/11 is turned into office workers fleeing for their lives from a bloodthirsty beast slowly ascending their high-rise building; the fears of early motherhood manifest in an actual kidnapper lurking on the front lawn of a suburban home; and, faintly reminiscent of the set-up in Yorgos Lanthimos’s recent film The Lobster, widows and widowers are confined to segregated state facilities until they pair off again.

We’re brought back to reality with the stories in We Don’t Know What We’re Doing. Centred around the Welsh castle town of Caerphilly, they combine to depict a rich portrait of a community. Morris’s subject is the everyday lives of ordinary people, but the collection as a whole is anything but.

And finally, Johnson’s second story collection features six protagonists, all of whom are lost in some way: a Silicon Valley coder who reanimates an assassinated president; a self-loathing paedophile; a former Stasi prison warder in denial about the past; a woman with cancer; a UPS driver searching for the mother of his son after Hurricane Katrina; and two North Korean defectors struggling with the freedoms of their new life in the South. It’s a stunning collection, each of the six stories a masterpiece in miniature; the depth and breadth of each, even for long short stories, is remarkable.

When it came to debuts, alongside The First Bad Man – a slightly surreal, often discomfiting portrait of an unexpected relationship between a middle-aged woman and a younger pregnant girl, full of exactly the kind of offbeat humour and testing boundary-pushing one would expect from Miranda July based on her previous film and art projects – Hausfrau – a deceptively clever modern take on Flaubert’s classic Madame Bovary about an unfulfilled American expat housewife and mother living in a Swiss suburb that considers the relationship between agency and language – and After Birth – Albert’s no-holds-barred exploration of womanhood and the importance of female solidarity and shared experience, especially when it comes to motherhood – I was also particularly impressed by six others.

Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper (Fourth Estate) was a glorious literary surprise. So rarely can one genuinely describe a new voice as truly ‘original’ but they certainly broke the mould when they made Zink. The Wallcreeper is a Grand Tour of birdwatching, eco-terrorism and infidelity, and begins with what I can only assume will be one of those first lines that takes on a life of it’s own outside of the text, gleefully quoted as much as that of The Go-Between or Pride and Prejudice: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.” Also well worth a mention is Zink’s second novel Mislaid – a story of racial transgression in the American South in the 1960s that employs confusion and coincidence in the vein of a Shakespearean comedy – not least because the two were published together as a boxed set here in the UK.

Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper (Fourth Estate) was a glorious literary surprise. So rarely can one genuinely describe a new voice as truly ‘original’ but they certainly broke the mould when they made Zink. The Wallcreeper is a Grand Tour of birdwatching, eco-terrorism and infidelity, and begins with what I can only assume will be one of those first lines that takes on a life of it’s own outside of the text, gleefully quoted as much as that of The Go-Between or Pride and Prejudice: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.” Also well worth a mention is Zink’s second novel Mislaid – a story of racial transgression in the American South in the 1960s that employs confusion and coincidence in the vein of a Shakespearean comedy – not least because the two were published together as a boxed set here in the UK.

Tasha Kavanagh’s tale of obsession Things We Have in Common (Canongate) sent shivers down my spine. This was one of the best examples of the unreliable narrator I’ve come across in a long time. Yasmin, a 15-year-old overweight unhappy loner, fantasises about saving the object of her obsession Alice, a popular and pretty girl in her year at school, from the clutches of a paedophile. But what begins as the overactive imagination of a lonely teenager gets swiftly out of hand, and the end result is genuinely chilling, not an easy achievement.

Christopher Robinson & Gavin Kovite’s War of the Encyclopaedists (Hamish Hamilton) was another unexpected delight. It sounded a bit gimmicky – two friends, one at graduate school in Boston, the other serving in Iraq, who communicate via updating a Wikipedia page they initially created about themselves in jest; actually co-authored by two friends whose bios can’t really be distinguished from that of their fictional counterparts – but it was completely engaging: Franzen meets David Abrams’s Fobbit.

My personal favourite on the Man Booker shortlist – not to mention my favourite of the entire year – was Hanya Yanagihara’s now infamous tale of the inescapable legacy of childhood sexual abuse A Little Life.”

Another title that had a certain amount of baggage was Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers (Faber). A cross between prose poem and novella, Porter’s tale of a father and his two sons grieving the loss of their wife and mother was inspired by Ted Hughes’s Crow poems. Crow, trickster-cum-babysitter, turns up in the family’s London flat and takes up residence until they no longer need him. Hughes is not exactly a writer to be engaged with lightly, but Porter makes shouldering such weight look effortless.

Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire (Jonathan Cape) also arrived with a good deal of fanfare, published just too late to be eligible for this year’s Man Booker but, I suspect, a strong early contender for next year. Ignoring all the hype (film rights were optioned by Scott Rudin prior to the book selling for $2 million), it’s a dense Dickensian portrait of a city and its people, New York in the late 1970s, a city of crime, graffiti, downtown punk rock and art scenes, at the heart of which lies a mysterious murder attempt.

Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire (Jonathan Cape) also arrived with a good deal of fanfare, published just too late to be eligible for this year’s Man Booker but, I suspect, a strong early contender for next year. Ignoring all the hype (film rights were optioned by Scott Rudin prior to the book selling for $2 million), it’s a dense Dickensian portrait of a city and its people, New York in the late 1970s, a city of crime, graffiti, downtown punk rock and art scenes, at the heart of which lies a mysterious murder attempt.

Last but not least, Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen (ONE) is an epic tale of sibling rivalry set in western Nigeria in the 1990s that combines African oral storytelling traditions with the majesty of Greek tragedy.

Understandably, The Fishermen made the Man Booker shortlist in what was one of the strongest line-ups in recent years. I was least excited by Ann Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread (Vintage), but that could well have been due to the strength of the competition she was up against. Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island (Cape) showed that he’s a writer more at home with the complexities of cultural theory than traditions like plot and character, but all the same, his story of a “corporate ethnographer” chasing “the First and Last Word on our age” was surprisingly engaging. Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (Picador), a tale of Indian immigrants struggling to make not so much a better life for themselves, but simply some kind of life in Britain, was heartbreakingly bleak at times, but nevertheless made for gripping reading. Although my personal favourite on the list – not to mention my favourite of the entire year – was Hanya Yanagihara’s now infamous tale of the inescapable legacy of childhood sexual abuse A Little Life (Picador), in the run-up to the announcement I was torn between putting a bet on either Sahota or Marlon James to win. James it was though, with his beast of a book A Brief History of Seven Killings (Oneworld) which, for the record, is neither brief nor does it limit itself to only seven deaths. The action spiralling outward from the assassination attempt made on Bob Marley in his Jamaican home in 1976, James presents a polyphony of voices, with an emphasis on Jamaican patois, and plenty of Tarantinoesque violence and sex.

However strong the shortlist was, I was disappointed and more than a little surprised that neither The Wolf Border nor Purity made even the longlist. Twice Man Booker-nominated Hall is one of the best British writers working today, and The Wolf Border is a wonderfully complex novel that explores the relationship between humans and the natural world through the prism of the story of one woman’s role in a scheme to reintroduce the grey wolf to the Cumbrian countryside.

However strong the shortlist was, I was disappointed and more than a little surprised that neither The Wolf Border nor Purity made even the longlist. Twice Man Booker-nominated Hall is one of the best British writers working today, and The Wolf Border is a wonderfully complex novel that explores the relationship between humans and the natural world through the prism of the story of one woman’s role in a scheme to reintroduce the grey wolf to the Cumbrian countryside.

When it comes to Franzen, I’ve always admired his work, but I have to admit that I wasn’t blown away by either Freedom or The Corrections in the same way as many readers were, so I approached Purity with some trepidation. However, it completely surpassed my expectations – apt given that it owes something of a debt to a certain Dickens novel, not least in the naming of the central protagonist. Pip is fresh out of college, saddled with debt and living in a squat when she meets a member of the Sunlight Project, a WikiLeaks-like operation orchestrated by the charismatic German-born Andreas Wolf. As the plot thickens, and we’re transported from the contemporary US via the hidden valleys of South America to East Berlin before the fall of the Wall, coincidence and connection abound, Franzen creating a plot of such tightly plotted interconnections he really would have given Dickens himself a run for his money. It’s sharp, clever and funny, and more importantly, a joy to read from start to finish.

Two other novelists, both ex-Booker winners, who had notable new novels published were Kazuo Ishiguro and Pat Barker. Ishiguro confused some readers with his tale of knights and dragons The Buried Giant (Faber), but beneath the fantasy exterior it was a novel that engaged with the same themes that have preoccupied much of his writing: memory, guilt and denial. Barker, whose Regeneration trilogy still remains the go-to fiction on the First World War, brought her trilogy about World War II to a close with Noonday (Hamish Hamilton), set in London during the Blitz. Although her characters are artists, she clearly took plenty of inspiration from writers such as Graham Greene, Henry Green, Rose Macaulay and Elizabeth Bowen, all of whom spent the war living and working amongst the bomb damage. Painting a rich portrait of a city under siege, its inhabitants living strange, somewhat disembodied lives.

I also admired Sarah Moss’s Signs for Lost Children (Granta), and Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies (William Heinemann). Moss is a writer about whom there quite simply isn’t enough fuss made. Signs for Lost Children is the sequel to the Wellcome Prize-shortlisted Bodies of Light, and is set between Cornwall and Japan in the 1880s. Ally Moberley, one of the first female doctors, works in the Truro asylum while her architect husband Tom Cavendish builds lighthouses on the other side of the world. There’s something quietly unassuming about the novel but Moss is absolutely fearless when it comes to examining the complexities of both heart and mind.

I also admired Sarah Moss’s Signs for Lost Children (Granta), and Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies (William Heinemann). Moss is a writer about whom there quite simply isn’t enough fuss made. Signs for Lost Children is the sequel to the Wellcome Prize-shortlisted Bodies of Light, and is set between Cornwall and Japan in the 1880s. Ally Moberley, one of the first female doctors, works in the Truro asylum while her architect husband Tom Cavendish builds lighthouses on the other side of the world. There’s something quietly unassuming about the novel but Moss is absolutely fearless when it comes to examining the complexities of both heart and mind.

By comparison, Fates and Furies was a novel that arrived dripping in hype, and continues to garner attention, with Barack Obama recently declaring it his read of the year. Written in rather baroque prose, it’s the story of a marriage split into two very distinctive parts – the husband’s account is told first, followed by the wife’s, and as expected we see a gulf between them open up as a consequence. What makes it so original and compelling a read are the particulars of their differing experiences, not least because Groff certainly doesn’t take easy options when it comes to depicting marital discord.

Go Set a Watchman turned out to be precisely what we knew it was all along: a first draft and an ultimately mediocre book with glimpses of something brilliant.”

Of course, the book that received the most hype this year was Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman (William Heinemann), the original draft she’d submitted before being told by redoubtable editor Tay Hohoff to abandon it in favour of a tale set earlier in the protagonists’ lives. This advice was clearly spot on as To Kill a Mockingbird went on to win the Pulitzer, not to mention a place in countless people’s hearts, as we all fell in love with young Scout as she watched her lawyer father Atticus Finch champion a black man’s rights in the segregated Deep South of the 1930s. The revelation that in the original book Atticus was a racist, reading pamphlets entitled ‘The Black Plague’ and espousing bigoted pro-segregation propaganda at citizens’ council meetings angered many readers, especially since this came after the ‘controversy’ surrounding the news the book was to be published at all, some reports suggesting that due to failing health Lee had been colluded into publishing something she had previously declared she never wanted to see the light of day. As expected, Go Set a Watchman turned out to be precisely what we knew it was all along: a first draft and an ultimately mediocre book with glimpses of something brilliant.

Another blast from the literary past arrived when a survey conducted by BBC Culture polling literary critics from outside the UK named George Eliot’s Middlemarch the best British novel. Indeed, the top five only features one novel written by a man – Dickens’s Great Expectations at number 4 – with Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway taking spots 2 and 3 respectively, and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre coming in at number 5. The poll’s top 20 titles are a half-and-half split between female and male authors, and take the 100 titles into account and female authors make up an astonishing 40 per cent which, as Hephzibah Anderson put it in her analysis, is “a notable achievement given that our critics have favoured works that have already stood the test of time, and were written back when it took infinitely more pluck and grit for a woman to break into print than her brother.”

This international celebration of women’s writing coincided with another blow against the white male privilege inherent in publishing as the #DiverseDecember initiative was set up by bloggers Naomi Frisby and Dan Lipscombe to encourage “a celebration of books by BAME [Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic] authors”. At the same time, Nikesh Shukla explained in the Guardian that when the 2016 World Book Night titles were announced at the end of November and none of them were by BAME authors, he had finally had enough. In response he decided to put together a plan for a collection of essays about race and immigration via the crowdfunded publisher Unbound. The entire thing was fully funded by the end of the second day (thanks to significant backing from white female author J.K. Rowling), and looks set to become a huge hit.

So, alongside Shukla’s The Good Immigrant, which other titles are worth looking out for in the next twelve months? Too many to choose from is the short answer, but a few already stand out from the pack. Garth Greenwell’s debut novel What Belongs to You (Picador), which Claire Messud called “the real thing” in just one of the many rave reviews that have accompanied the American publication. (Plus Greenwell wrote an astonishingly good analysis of A Little Life in The Atlantic, so in my eyes can do no wrong!) Then there’s Helen Ellis’s American Housewife (Scribner) the praises of which none other than Margaret Atwood has been singing.

So, alongside Shukla’s The Good Immigrant, which other titles are worth looking out for in the next twelve months? Too many to choose from is the short answer, but a few already stand out from the pack. Garth Greenwell’s debut novel What Belongs to You (Picador), which Claire Messud called “the real thing” in just one of the many rave reviews that have accompanied the American publication. (Plus Greenwell wrote an astonishingly good analysis of A Little Life in The Atlantic, so in my eyes can do no wrong!) Then there’s Helen Ellis’s American Housewife (Scribner) the praises of which none other than Margaret Atwood has been singing.

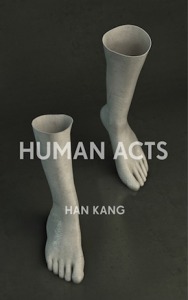

I’ve also got high hopes for Rachel B. Glaser’s tale of female friendship, Paulina and Fran (Granta); Human Acts (Portobello) by Han Kang, author of the stunning The Vegetarian; Ian McGuire’s gritty nineteenth-century set story of dark doings on a whaling ship, The North Water (Scribner); My Name is Lucy Barton (Viking) by Elizabeth Strout of Olive Kitteridge fame; Gerard Woodward’s new story collection Legoland (Picador); Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen (Cape), a book that got rave reviews on its publication in the US; Robin Wasserman’s Girls on Fire (Little, Brown), which apparently rivals The Virgin Suicides when it comes to a portrait to female adolescence; Milena Busquets’s This Too Shall Pass (Harvill Secker), which is being described as Joan Didion meets Elena Ferrante – one hell of a claim and two amazing reputations to live up to – and Mary Gaitskill’s The Mare (Serpent’s Tail), the story of a Dominican girl and the white woman who introduces her to riding.

Lucy Scholes is a contributing editor to Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern, Tate Britain, the BFI and Waterstones Piccadilly.

@LucyScholes