Han Kang: To be human

by Mark Reynolds

Author portrait © Park Jaehong

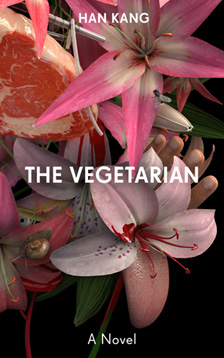

Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, her first novel to be published in English, is a haunting, startling and poetically rendered story about shame, alienation, rage, metamorphosis and desire in present-day South Korea. I meet her, with translator Deborah Smith and interpreter Kyeong-Soo Kim, to discuss its themes of identity and humanhood.

MR: The Vegetarian was published as three short novellas in Korea. Were they always planned this way; were all three completed before the first was published; and is the publication of a series of very short works of fiction as unusual in Korea as it would be here?

HK: It does exist in Korea, serial stories individually published first and then published together. Not a lot, but I would say we have more serial novels there than here in the UK. I began to write the stories in 2000, and I wrote the first two parts of the story together over two years, and then they were published. Then much later I wrote the third part.

Deborah, when did you first encounter The Vegetarian, and how did you go about becoming its translator?

DS: In 2011 And Other Stories contacted me to ask if I would do a reader’s report on the book for them, and translate a small sample. At the time I had only been learning Korean for about a year and a half, and I knew about the book because I was interested in translating Korean literature, but I hadn’t done any work in publishing and I didn’t really know what a reader’s report entailed, and I didn’t quite understand about the sample either. Of course I was very enthusiastic and said yes, but was too mortified to get back to them and say I’d never read a book in Korean before. So I hacked through a horrifically bad sample, which obviously explains why they didn’t take the book. Then a couple of years after that I was at the London Book Fair, the year before the Korea Market Focus when they had a couple of Korean authors over to prepare and they invited me as well, and I met up with Max Porter, who’s the editor of Granta and Portobello. He asked if I had any Korean books and I instantly thought The Vegetarian would be perfect for their list. I emailed him a much better sample which I had polished up, and a bit of publicity info about the book as well, and he emailed back the next day and said that he loved it.

At what point were you approached about a film adaptation, and in what ways does the film differ from the book?

HK: The director who made this film (Woo-Seong Lim) is a friend of mine, and he had wanted to make a film adaptation of my book for a long time, but I hesitated for a bit. Then I think it was in 2008 he actually began to make the film. My impression of the film is… ‘complicated’. I guess it was inevitable that the director turned it into something quite different from the images that I thought it would make. That’s as much as I can say.

How unusual is it to be a vegetarian in Korea, and why did you choose to examine this particular act of non-conformity?

HK: First of all, in Korea, we don’t really eat a lot of meat compared to people in the West. We eat tofu, bean curd and other vegetables all the time. Koreans don’t usually declare they are vegetarian even if they are because they can just avoid meat from the meal table, which is full of vegetables anyway even when meat is served. So to declare “I’m a vegetarian” as my protagonist Yeong-hye does is to make a big statement. For her it is a way to protest against the violence humans live with and take for granted. The reason that I chose vegetarianism is that it could be seen as a perfectionist way of being pure, in that it’s not committing any kind of violence.

To what extent are metamorphosis, identity and self-determination recurring themes in your work?

HK: I’ve always had this question, what it means to be human, it’s something I’ve been living with unendingly. A little over a year ago in 2013 I wrote a novel about a young boy who was killed in the Gwangju massacre of 1980 when I was 9 years old, and I think this incident had a big influence on my writing. It was the basis of that unending question, what it means to be human and to accept the fact that we are human. In this book, Yeong-hye wants to transform her body. In another novel, Greek Lessons, there’s a character who refuses to speak, refuses language. So yes, the three themes you mentioned continue to be subjects in my novels.

“Hypnotically strange, sad, beautiful and compelling.” Nathan Filer

Visual art is another strong element in The Vegetarian and, I understand, in your other work too. What would you say that visual art can convey more strongly than literature, and vice-versa?

HK: It’s not that I rely on visual images in place of language. I tried solely relying on language but at times, maybe because I like visual art, I find images that sort of creep in on my writing. I think visual art can be very strong in terms of making an impact on the intuitive or instinctual level. But I do believe that the force of literature is strong in driving the question about humanity, and to delve into that question I think we have to borrow the voice of literature.

DS: There’s visual art in Han Kang’s work, but also other kinds of art like plastic art. She wrote an earlier novel called Your Cold Hands, which has a character who is a sculptor, and in the most recent novel there’s a theatrical production as well. And what’s interesting about how Kang uses art in these books is more about the failure of art as a form of processing trauma or feelings or desire. Where you would conventionally expect the characters are hoping for some kind of catharsis and consolation through art, they typically don’t find it. And so their engagement with art actually becomes quite dangerous, they become more mentally unbalanced or their trauma ends up affecting them more deeply rather than being appeased, which I think is a particularly interesting take on art in literature, because more often you would find the other way. Also for me when I’m translating, because Kang is so interested in visual art and images, the images are not necessarily themselves in the text, but, for instance in The Vegetarian the three sections are so distinct in terms of their mood and their tone that they exist, for me, as images, and so I’m translating the mood, the tone, the atmosphere from the original into an English which will hopefully evoke a similar image for the English reader, without actually putting these images directly into the text.

The dull, conventional and risk-averse Mr Cheong can certainly be blamed for sparking Yeong-hye’s passive resistance and mental instability; while In-hye’s husband ‘J’ stretches the limits of acceptable art and social behaviour. Who would you consider to be the most subversive – or the most dangerous – character in the book?

HK: First of all Yeong-hye is conscious of being capable of self-sacrifice in saving, let’s say, a young child falling on a train track, but she’s equally capable of the same extreme violence as the rest of humanity. Being aware of this wide spectrum of human nature, Yeong-hye tries to eliminate, completely rid herself of the violent side of being human, and that is why she decides to become vegetarian. I purposely did not give any voice to Yeong-hye. She is observed as an object sometimes of hatred, sometimes of fear or pity or compassion, and sometimes the object of complete misunderstanding. I wanted readers to work out her true face. Because of all these oblique lines approaching her, we can’t really see the truth of her, but I hope that if you keep following the lines you can ultimately find her.

The only time we hear directly from her is in the dream sequences, which are particularly traumatic.

HK: Yes, only then.

DS: For me the most subversively presented character, or the one who is possibly the most interesting because of how they view Yeong-hye is her sister, In-hye. It’s quite easy to see Yeong-hye as an object of fear or prejudice or repressed desire – but in the final section In-hye at times sees her as an object of envy. In-hye herself is the dutiful daughter, wife, mother, sister, she has been living a completely conventional life, and here is her sister going completely beyond the pale. She pities her greatly, she wants to understand her, she becomes angry, but she also envies the way that Yeong-hye has completely broken free of what’s expected of her. There’s a passage where she says something like Yeong-hye has soared so high and left her here in the mud. She feels there is a kind of freedom in her act of sacrifice, even though obviously there’s a pretty big price to pay.

The intense and sexually charged middle story, ‘Mongolian Mark’, put me in mind of Yasunari Kawabata’s ‘House of the Sleeping Beauties’. Which authors, if any, have most influenced you work?

The intense and sexually charged middle story, ‘Mongolian Mark’, put me in mind of Yasunari Kawabata’s ‘House of the Sleeping Beauties’. Which authors, if any, have most influenced you work?

HK: I don’t know that story. Perhaps it hasn’t been translated into Korean. Before I wrote The Vegetarian, I wrote a short story called ‘The Fruit of My Woman’, which is a story about a woman who actually turns into a plant. Her husband puts her in a pot to look after her once she has become a plant, but until then they didn’t have a good relationship. I wanted to take that further, and I began to write this book with that intention, but it just took on a completely different form, very dark. I recently attended a reading in Berlin and the topic was comparing my book to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. Someone asked if I was inspired by Kafka, but actually I think pretty much everyone reads Kafka when they are in their early teens, and I think The Metamorphosis has become a part of all our lives, so I can’t say it was a direct influence. There’s also an ancient story in Korea about an old scholar who, after a hard day’s work opens the door to a room, goes in and it’s filled with plants. He talks to the plants and he sleeps among them and that’s how he finds his rest. It’s not that I wanted to follow the storyteller’s footsteps, but I think all these little things are linked as influences. It’s a beautiful image. The image that inspired me was an image of a woman turning into a plant.

A much broader question, is Korea’s old value system crumbling – and which aspects of traditional society, if any, are worth keeping?

HK: Well, Korea has undergone so many changes so quickly, but I wouldn’t say everything has crumbled or collapsed. Rather, a lot of things have become kind of hybrid. I was born in 1970 and up until 1980 before I moved to Seoul I lived in a traditional home setting, where I experienced a sense of community. People knew one another in the neighbourhood. But that was very brief and only lasted till I moved to Seoul. I would think that was part of the traditional sense of Korea.

In what ways has the new wave of women writers in Korea since the 1980s changed the literary landscape?

HK: By the time I first began publishing my work in 1993, Korea had established a real democracy, so people were writing different stuff. Up until then, especially writers of the 1980s, they were focusing more on democratisation or themes designed to go against the government, and I think they were rather under pressure. I was lucky to have come in during a time that didn’t have to deal with those issues. So women writers of the 90s, including me, were able to progress much further and with more freedom than those of the 80s.

DS: I think partly it is as Kang says more a general opening up, not solely for women writers. There was a broadening of themes that could be explored, and I think the very strongly ideological, political, social-realist work that had been written before then just tended to have been written more by men, because that was possibly more of a male field. After democratisation was achieved there was more room for a more personal, private interpretation of history, based on other kinds of experience that were not national or military, or the fields that men were mainly involved in.

And what kind of difference has it made now Korea has a female president? Albeit that she’s the daughter of a past dictator.

HK: Actually since Park has become the president, a lot of people are undergoing pain.

DS: It’s not really so much about her being a woman, it’s who her father was and especially for someone like Kang from Gwangju, where the massacre took place.

HK: The current situation in Korea, having a new government led by Park Guen-hye, certainly allowed me to revisit the Gwangju massacre. Continuing on my never-ending question of what it means to be human, this was the incident that first instilled that deep question in me as a teenager. It’s not that I wanted to re-create the incident, I know a lot of other writers have covered this issue, it’s just that I wanted to look at it from a different point of view, I wanted to revisit it for my own sake. I thought Korean society is going backwards now, and I needed to revisit the Gwangju issue that Korea never really resolved.

And that book has already been published in Korea. How was it received?

HK: It was very well received.

DS: Portobello will be publishing it next January. The end of next month is the deadline for finishing the translation, and we’re nearly there.

Could you say a little about your path to becoming a translator of Korean literature? I understand you learned the language specifically to make that move.

DS: Yes, I did. I’d studied English Literature for my Undergrad, but I hadn’t really engaged with that as much as I thought I would because prior to that most of the books I read were in translation, and I found the focus on just reading writers who wrote in English for three years incredibly narrow. Also I was faintly embarrassed that, like so many people who’ve had the same education as me in this country, I was 21 years old and could only speak English. So I wanted to become a translator because it seemed to fit in with all my interests. I liked creative writing, I liked reading books in translation, I liked the idea of learning a language, I suspected I’d enjoy that, and Korean was the language that stood out because there were pretty much no Korean books available in English. What little I knew of Korea was that it was a very developed, modern country with an incredibly high literacy rate, so I just assumed there would also be a vibrant literary culture there, and luckily all those things that I assumed have come true and paid off. It was really through The Vegetarian, once I’d made the decision to learn Korean and study the literature, that I was able to get my foot in the door for translation. It was just a sequence of incredibly lucky coincidences. Mainly that Korea was chosen as the Market Focus country for the book fair, and so suddenly people wanted to find a Korean translator in the UK, and there was no one else. So, much earlier than I would have attempted to start translating under my own steam, I was given the impetus.

How many different works have you translated by now?

DS: Aside from The Vegetarian, I have pretty much finished translating the new book, as well as parts of a couple of Kang’s other books, including the short story ‘The Fruit of My Woman’. I’ve translated a couple of books by another female author called Bae Suah, parts of which have been published online and contracts are in the works. Han Kang and Bae Suah are two of my favourite authors, those are the kinds of books I would choose to read from any language. But I also enjoy translating books that I wouldn’t necessarily choose to pick up, just because it’s such a different set of challenges, something that’s full of slang or humour or more in the vein of traditional Korean storytelling from some of the older writers.

What are the particular challenges of translating from Korean into English?

DS: I think all of the challenges, and it’s not just a cliché to say it, they are opportunities as well, they are what’s enjoyable about it. Because the languages are so far apart, it’s impossible to be faithful to syntax and grammar in a way that perhaps you could between, say, English and French or other romance languages. So that gives you more freedom as a translator to be faithful to what I would consider more important aspects of the original text. Especially when I’m translating Han Kang, I will be faithful primarily to things like the tone, the mood, the atmosphere, to the way her language is lyrical but not in a set, rhythmic way that we might expect from English. It’s a little bit more disrupted, a little bit more oblique, understated.

The other thing is the cultural context. Korean culture is still so little-known in the UK that there will inevitably be things in almost all books that English readers won’t know about. As long as I can make it clear without disrupting the text what things are, as far as it’s necessary, then I will do that. But sometimes people who mainly theorise about translation or teach rather than actually translate will get incredibly caught up on, you know, how are we translating this exact type of fish, or this particular kimchee? For the most part it’s not necessary that the English reader know because it’s not a cook book, and it’s not anthropology, it’s literature, so don’t weigh it down with a footnote or a mass of description of what kind of radish it’s meant to be.

Which other Korean writers should we be reading?

HK: Older, more established writers have pretty much been introduced, I think. I would like to see more contemporary writers introduced, for example Hwang Jung-eun.

And what are the latest non-Korean books you have read?

HK: I was in Poland for a term from September to December last year, so I’ve been reading a lot of Polish authors. I really enjoyed reading Olga Tokarczuk. I’m also enjoying Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home.

DS: I finally got round to reading Melville’s ‘Bartleby, the Scrivener’. The thing that prompted me was one of the reviewers of The Vegetarian mentioned that he had been reminded of Bartleby and the literature of refusal and renunciation, so that was very interesting. I also read Panty by the Bengali writer Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, which was translated by Arunava Sinha and published by Penguin India. It wasn’t made available here but I ordered it through the internet, and that was completely eye-opening. I’ve been reading as many Indian authors in translation as I can find, and seeing how different what they are writing is from what’s being written by Indian writers in English.

Kang, you teach creative writing. What is the first piece of advice you give to your students?

HK: It’s seven years since I began teaching, and I always wonder what part of literature I can really teach. I think students have to learn on their own, so my first advice is to read a lot, to be immersed in reading. That’s all.

And Deborah, what advice would you give to someone looking to set out as a literary translator?

DS: Absolutely the same, read a lot. Having a literary sensibility is absolutely the most important thing for being able to translate. And that hasn’t been what’s been focused on, especially with Korea. It’s been cultural knowledge – and linguistic knowledge as well, I suppose. Because I’ve had a different background, I tend to emphasise a wide literary awareness over knowing exactly what every word means. I certainly didn’t know exactly what every word means when I started translating, and I still don’t know what every single word means, but I have Korean friends like Kyeong-Soo who I can ask, and the internet exists, dictionaries exist. But there is no dictionary that will tell you what literature is. On a more practical level, just talk to other translators, even if they are not working from your language. In London we’re lucky, we have the Emerging Translators Network. The American Literary Translators Association are setting up something similar, and in Korea the Literary Translation Institute has been incredibly supportive and has a lot of contacts. So don’t try and sit in your room on your own and think it will all just happen.

Read an extract from The Vegetarian at Words Without Borders.

Hang Kang and Deborah Smith at the 2014 London Book Fair

Han Kang was born in Gwangju in 1970 and moved to Seoul at the age of ten, later studying Korean literature at Yonsei University. She made her literary debut as a poet in 1993 and has since published collections of short stories including Love in Yeosu, A Yellow Patterned Eternity, and The Fruits of My Woman as well as novels including Your Cold Hand, Black Deer, Greek Lessons and The Vegetarian. Her writing has won the Yi Sang Literary Prize, the Today’s Young Artist Award, and the Korean Literature Novel Award. She currently teaches creative writing at the Seoul Institute of the Arts. The Vegetarian is published by Portobello Books. Read more.

Deborah Smith is currently translating the latest novel by Han Kang, which Portobello Books will publish in January 2016. Alongside this and The Vegetarian, she has also translated several books by Bae Suah, including The Essayist’s Desk and The Low Hills of Seoul. She is currently finishing a PhD in Korean Literature at SOAS, and has recently founded Tilted Axis, a not-for-profit press which will publish translations from non-European languages. @londonkoreanist

Kyeong-Soo Kim is a freelance interpreter currently pursuing a doctorate at SOAS in Korean literature in translation.

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.