A minority of one

by Richard Tyrrell

WILF KELLY WAS RICH IN TIME.

After the sudden death of his young mum thirty years ago, he lost his job. He’d swept bottles of wine onto the supermarket floor and stood in its mess, silent and swaying. The store fired him. He never found work again – and never tried. Time became his personal wealth.

Now he lived alone and clung to comforting routines, like his Metro round. Nobody bothered him except kids on the streets calling him ‘Worzel’, ‘Beetlejuice’ or ‘Smelly Kelly’.

Sometimes they held up phones and filmed him. When he saw their malignant little hands rising, he put his head down and walked away.

He had lots of imaginary tormentors who were neighbours going about their business. Daily they looked at him with an expression of pity, tried to speak to him, and said things like, ‘Are you okay, Wilf?’

…

One of his routines was to take walks in Kensal Green Cemetery. He loved its memorials, trees and bushes. His mum had told him thirty-three species of birds nested there. He picked blackberries each August, from a mass of brambles overgrowing a plot of 1910s graves. It was like the unbeating heart of London, where he could be ignored in peace.

On one of his regular strolls, his eye was caught by a flash of red among gravestones. The biggest fox he ever saw broke cover. It trotted onto the path and stopped to stare at him.

He saw its resentful eyes and the pale fur under its snout radiating into a chest ruffle. As abruptly as it stopped, it lost interest and twirled away into a thicket.

Wilf felt mesmerised and had to follow.

He crossed a rough patch, skirting graves verge by verge. He imagined his foot being sucked underground. Finally, he steadied himself on a Celtic cross and peered into the trees, trying to penetrate the foliage.

It was a big dog fox. Like him, it must live alone. It must go out at night foraging in the streets for fallen kebabs or fried chicken. Wilf entered the thicket, ducking under branches. He saw another flash of red and made his keynote sound – one he often made when he saw people he knew or realised he was being stared at.

‘Hrymmphh.’

The fox’s head appeared from behind leaves. Its ears pointed forward as if Wilf had guessed its name in vulpine language. He said again,

‘Hrymmphh.’

But that was the end. The animal fled. Wilf heard the swish of leaves as it loped away.

But he knew then and there his friend Felicia was right. If he was ever to be normal, he needed a pet.

On one of his regular strolls, his eye was caught by a flash of red among gravestones. The biggest fox he ever saw broke cover. It trotted onto the path and stopped to stare at him. Wilf felt mesmerised and had to follow.

Felicia O’Dwyer was the only friend left in the tree streets neighbourhood who’d been in school with him. She was the same age and still lived on Yew Road in the house opposite his. She had children and grandchildren now.

When she was a crazy kid, her gang found an old bin and she curled up inside it while they rolled it on the Green. Felicia was spun and spun, laughing. Wilf watched from nearby. On an impulse, he jumped onto the bin and tried to run with its roll. He bobbled along for a few moments, then ended up flat on his face.

Felicia found it hilarious. But when her friends started to jeer him, she helped him up, licked her fingers and wiped grass from his cheeks.

‘Piss off,’ she told her mates.

From then on, he was in her protective custody. If someone nudged his arm as he drank milk at school, she threw milk at them. If someone barged into him, she barged into them. When a group of boys stood in a crescent crowding him, she kicked the biggest on the ankle.

‘You know,’ said her mother, who wasn’t entirely comfortable with this, ‘that little boy’s not normal like you, Felly.’

‘He’s not stupid, Mam,’ said Felicia. ‘He’s really clever.’

‘All the same… don’t get too involved.’

But Felicia ignored her mother’s warning.

Most of the time, in school classes, he sat in a back corner, his eyes elsewhere. When they fell on her, she could sense him feel relief. She started sitting at the desk beside him. Occasionally, he whispered something to her, and she’d raise her hand and say, ‘Sir, Wilf says the answer is…’ He was always right.

After his mum’s funeral, Felicia led him home and cooked a meal. And put plates of food in front of him, at least once a week, ever since. And did his laundry, coaxed him into her house for a hot shower, trimmed his hair and bought some, not all, of his clothes from charity shops.

He never said ‘Hrymmphh’ to her.

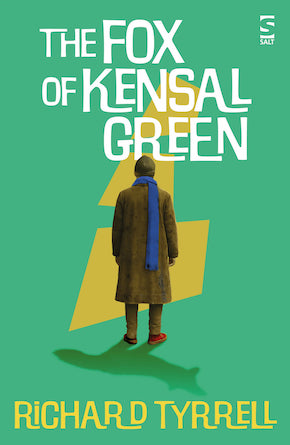

from The Fox of Kensal Green (Salt, £10.99)

—

Richard Tyrrell was born in Ireland and graduated in Pharmacology at University College Dublin before turning to writing. He lives in Kensal Green, North West London. His poems have been published widely in literary magazines, and he was a trustee of the UK Poetry Society, serving as its first Irish Chairman. He was a finalist in the Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting and on Channel 4’s The Play’s the Thing. The Fox of Kensal Green, his first novel, is published in paperback by Salt, and in audio by W. F. Howes. Spanish and French editions are also in the pipeline, with Automática Editorial and Éditions Philippe Rey.

Read more

facebook.com/richard.tyrrell.58

@saltpublishing.com

instagram.com/saltpublishing