A sitting duck

by Bill Knox

The plan… It had first taken shape in Renfield’s mind one morning over a month before when the 29-year-old reporter, on the staff of the Evening View, had been having a casual 10a.m. cup of tea in the canteen at Glasgow police headquarters.

The big room, reserved for sergeants and constables, with pressmen having an unofficial membership right, was quiet. Sergeant Breaden, a bulky six-footer, joined him at the small plastic-topped table, in an affable mood. His good humour had been brought about by just seeing a pet ‘ned’ – a descriptive phrase which covers the multitude of Glasgow’s lesser louts – sentenced by the Sheriff to six months’ imprisonment for assault.

The ‘ned’ in question had attacked another gentleman whose worth to the community was of rather negative value. The sergeant and a constable had hauled the attacker off his victim just before the traditional coup de grâce of a kick on the head from a heavy boot was about to be applied.

“How’s it going, David?” asked the sergeant, who knew Renfield of old as ‘police calls’ man for the View, responsible for the gathering of routine information from various police channels, collector of tit-bits in the form of safe-blowings and sudden deaths in quiet times, by-line crime reporter when big news reared its head in the city.

“So-so,” replied Renfield. “The Lost Property Department have a couple of sheep on their hands – the four-legged variety. A character found them on his tenement landing this morning, practically swore off the booze before he found they were real. They’ll have strayed from the Meat Market, I suppose.”

“Aye, things are always quiet in mid-week,” agreed the sergeant. “Thursday onward till Sunday morning is our busy part of the week. Thursday’s the day when the thugs are on the assault and robbery prowl, flat broke and knowing there are plenty of places sending out for Friday’s wages, or banking their takings.

“Friday morning – that’s the time when all the overnight safe-blowings are discovered. The ‘petermen’ have a ruddy genius for smelling out firms with tin-can safes and a habit of drawing their pay packet money on Thursday.

“As for Saturday – anything can happen then, and usually does, especially after the pubs are shut. The backwash of all the drunken brawls don’t die away till pretty near dawn on Sunday. But after that, at any rate, we get time to collect our thoughts.”

Renfield, agreeing with the sergeant’s summing-up, commented, “And the shocking thing is that none of our local crooks seem to have any respect for evening paper edition times. If it’s a street robbery, they always do it about ten minutes before the last edition. If it is a safe-blowing, then they make so much noise that it is discovered almost immediately, and the morning papers get first nibble at the story. You should train them better than that, Sergeant.”

“What really riles me is the senseless way in which shopkeepers send these unguarded messengers to the banks,” growled the sergeant.

“We get the same thing happening every week,” he complained, pouring some more milk into his cup, and unwrapping the little parcel containing his mid-morning sandwich.

Renfield was no longer listening. A wild, crazy notion had sprung into the young reporter’s mind.”

“These idiots send a kid of about sixteen along to the bank with a nice big bag of lolly to put away, or a packet of money to collect for wages. They send them out at the same time, over exactly the same route, and always the same wee girl – or, at the best, some old fellow the wrong side of sixty. Then the fools wonder when some bunch of spivs clatter their messenger over the head and get away with the loot.”

“Fair enough,” interrupted Renfield. “But quite a few times you find that the sweet little girl or the dear old dad is in on the robbery and only got thumped over the head for effect. They get a lump on the skull – and a nice fat cut of the proceeds.”

“That does happen sometimes,” admitted the sergeant, then he looked up as another uniformed figure approached their table.

“Hello, here’s old Lawson,” said Breaden, as the second sergeant joined them. “Here, Jack, I was just telling the lad about the daft habits of our local shopkeepers when it comes to collecting money from the bank.”

Lawson sniffed, thumping down his cup and saucer on the table and pulling in a chair.

“Aye, and believe me, the big firms are just as bad,” he agreed. “Take Swivneys.”

Renfield forced a look of intelligent anticipation on his face, though he had troubles enough without having the moans of the city’s police unburdened on him. Still, there might be a feature piece in it for the View, and McRowder, the news editor, faced with a bare diary and consequently crotchety, would be grateful.

“Take Swivneys,” said Sergeant Lawson again, gulping a mouthful of tea. “They send out a ruddy great black Rolls Royce each Thursday afternoon with a chauffeur and cashier, pick up their payroll – must be about seven thousand pounds, it’s for the entire factory – then drive back again. They are out in the ruddy wilds of factoryland, yet they use the same backstreets route every week, the same car, and only one poor devil of a young cop to guard the lot. One day some of these London car bandits are going to come up here and knock off the whole payroll.

“You know what the streets are like in that part of Glasgow… only the odd lorry or car now and again, quiet as the grave most of the time. That car’s a sitting duck.”

The talk turned to football seconds later, and the two sergeants began arguing about the merits of the current Glasgow Rangers forward line. But Renfield was no longer listening. A wild, crazy notion had sprung into the young reporter’s mind.

He made no mention of the sergeants’ complaints when, an hour later, he returned to the View office. Head in an unsteady whirl of confused, half-formed ideas, Renfield entered the lift, stabbed the second-floor button, and waited impatiently till the cage stopped at the editorial flat.

He walked past the bustling subs’ desk and over to the reporters’ room. Waving a perfunctory greeting to the few reporters in at that hour, either just back from assignments or killing time until their particular tasks came round, he pulled his typewriter from its locker.

“Let’s get rid of this junk, then maybe I can think straight,” he muttered, slipping paper in the machine and opening his notebook.

Apart from the mystery of the two sheep, there were only two small stories that had been handed out by the Enquiry Department at the police station. One sought witnesses of an accident, the other was an attempt to identify a lost memory case in a city hospital. But all the time he worked he was repeating to himself the sergeant’s words – “The same route, the same time, the same car, and only one poor devil of a cop to guard the lot. The car’s a sitting duck.”

It was, so far, only a slender, colourless thread. But it might yet weave a moneyed pattern which could clear away his torment, a torment he alone knew existed.

There was the money, seven thousand pounds, the policeman had said, waiting, begging to be taken. And there was Jean Catta, dark-eyed, full-figured, heady.

Jean, with her passionate regard for gaiety and clothes, perfumed elegance and the good things of life. Jean, who was a fashion model with a doctor father, and who openly declared her intention of marrying only a man who, in addition to attracting her, could adequately supply the luxuries of life.

He at last faced up to the fact that money, big money, was the only language which would ever really sway the girl. She was like a drug to him – overpowering, heady.”

Renfield had first met her when her employer’s shop had been broken into by a couple of thieves whose taste ran more to the contents of the petty cash box than the exclusive dresses lining the walls. She had posed for a couple of pictures after the manager had decided that the publicity from the break-in would be an asset to the end-of-season sale due to begin the following week.

“Like a copy of the pictures?” he had asked her, as the photographer arranged the scene to show the maximum of her figure and the minimum of the damaged desk from which the money had been taken.

She had eagerly accepted the offer. Back at the View, Renfield had to argue with the photographer, who was also young, single and interested in the dark-haired girl. Renfield finally won on the toss of a coin, and wandered up to the shop that evening, armed with an envelope containing two glossy prints of the pictures.

Jean had emerged, expressed surprise at the encounter and at his remembering his promise, and, after a moment or two, had agreed that the photographs must be discussed over a drink.

“Just a few minutes,” she had warned. “I’ll need to get home after that.”

The ‘few minutes’ had ended at nearly midnight, with a promise of further meetings.

That had been some months ago. Renfield held Jean, temporarily at any rate, with the supposed glamour of his job as a crime reporter, with his hire-purchased car, and the way he was draining his savings in an effort to provide the silk-lined luxury which was demanded by Jean.

But just a few evenings previous, there had been a temperamental storm, one of several of late, all over the fact that Renfield, unexpectedly working overtime on a story, had turned up tired, dusty, and an hour late for their date. Jean had had to cool her heels in the restaurant lounge – and no explanation would reduce her rage.

She was bitter without being savage, tremulous without bursting into tears.

“I’m not used to this sort of treatment,” she had warned him. “And I don’t intend becoming used to it either.”

A beautifully worked silver charm bracelet and a long, appealing letter went to her home the next day. Between them they mended the break – but the bracelet sliced another nine pounds from Renfield’s thinning bank account.

And he at last faced up to the fact that money, big money, was the only language which would ever really sway the girl. She was like a drug to him – overpowering, heady. But despite all the perils she threatened, he knew he had to have her – needed her with a craving that at times terrified him.

Was this the solution? “The same route, the same time, the same car, and only one poor devil of a cop to guard the lot.”

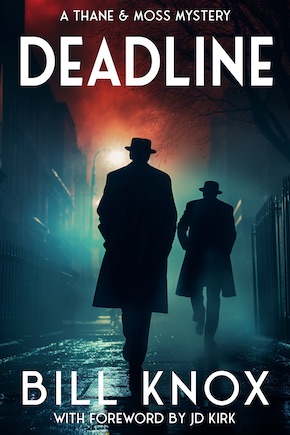

from Deadline (Zertex Media, £9.99)

—

Bill Knox was a Scottish crime author, publishing sixty-five novels over his lifetime. His most notable works include the Thane & Moss Series. Working as a journalist and broadcaster, Knox was also well known as the host of Tales of Crime. In his lifetime Bill received the 1987 CWA Award for Most Authentic Novel with a Police Setting and the 1989 Paul Harris Award. The first three Thane & Moss novels – Deadline, Death Department and Leave it to the Hangman are now reissued by Zertex Media in paperback, eBook and audio download.

Read more and buy from Amazon

@zertexmedia

Author photo courtesy Susan Ward