An absence full of presence

by Mika Provata-CarloneWhat You Did Not Tell: A Russian Past and the Journey Home by Mark Mazower is an eloquently written rhapsody on the art of remembering. It is rhapsodic both in the primary sense of the word, in that it is a chronicle exuding a certain air of poetry and exalted, almost epic feeling, and in the more literal sense of being a fabric of words, facts, events and lifelines retrieved from memory and archive and stitched together to form a long-silenced record of a life, an era, a time in human thought and action. A rhapsody consists of poems of valour stitched together into an epic whole – and Mazower’s book is such a quilt of patches of memory, swatches of evidence, threads of historical inquiry given shape and body thanks to a formidable determination to defeat both nostalgia and oblivion.

To call What You Did Not Tell a quilt-like achievement is not at all to berate it. Its very purpose is to reveal the epic subtext behind “a life that illustrated… the pursuit of contentment and well-being… Of a life lived across generations as a story not so much about suffering and the isolation and loneliness of an authentic individuality, as about resilience and tenacity and the virtues of silence and pragmatism, and taking pleasure in small things.” If Tolstoy praised the exceptional richness of an unhappy life, Mazower, the last in a long line of family storytellers, speaks of the historical force that is a life of stability, even if (especially if) it follows a path as radical in its revolutionary fervour as that of his grandfather, Max Mazower.

Ask a historian a simple question and you certainly do not get a simple or straightforward answer. History is all about connections, complexities, implications, absences, in as much as it is about hard facts and evident realities, and Mark Mazower is a historian endowed with the gift and the compulsion to tell stories, with the tenacity to delve deep and to walk on paths long overrun by falsehood and obscurity. Since his first academic work, clearing up cobwebs and resurrecting voices has been an acutely recognisable driving force in his writing. The journey of What You Did Not Tell begins, at least nominally, after a funeral, the funeral of Mazower’s father. A guest asks what had been the funeral rites for his grandfather, and this relatively simple enquiry of family ethnography entails a 400-page foray into a past that is hard to define, let alone piece together. A question about how a body was disposed of after death becomes an act of unburial, an examination of how that man had disposed of his own life, how he had lived it, inherited it from parents but also from a culture far greater than any individual, how he bequeathed it onwards to future generations. And with this resurrection of a life there is the reanimation of an era, a lost society, a modus pensandi that was silenced, even deliberately erased, from the private and the collective mind in the interest of political survival or of a more conventionally recognisable existence.

Connections and disconnections, stories and alternative versions, intermarriages and severed roots all make a single history impossible, and all the more pressing.”

Layers of darkness are lifted to reveal the single protagonist of history and of this story. “I thought about nostalgia and what precedes it,” writes Mazower early on, thinking perhaps about nostos, the yearning of homecoming, almost always inextricable from the pain of return, as “a way to withstand the pain of history.” For his grandfather, “the building of a home and political disillusionment could not be separated” – an assessment that betrays both acuity of feeling and perception, and a certain longing, perhaps, for a different life-gesture. In his grandfather, Mazower “saw something exemplary for our more jaundiced age with its demagogues and its obscene wealth and its even more intense introspectivity.” Windows in dusty archival rooms will be thrown open, the air shall be cleared, the eye will rove beyond its own centripetal orbit.

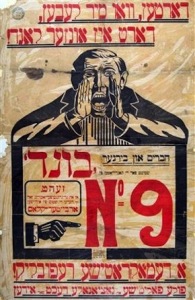

The history of one family is never an isolated account. No family crosses the firmament of humanity as a singular blazing comet. Connections and disconnections, stories and alternative versions, intermarriages and severed roots – all make a single history impossible, and all the more pressing, precisely because of the dense web of genealogies and events involved. Max Mazower’s story is a chapter in the story of Jewish Russia, of the almost forgotten Bundist movement, the Revolution and the ensuing, tragic disillusionment with its proclaimed dreams and visions. It is a personal, ecumenically resonant account of choices of self-definition, of ideas and ideologies, roots and absent spaces, of worldviews and factual reality. It is a poignant retracing of the many lives that go into the telling (and the living) of a single life, of the many books, sources, archives evoked to add flesh to bones, ghosts to streets, buildings and noise to places of devastated modernity and post-historical desolation. To speak the trauma of the untold stories of suffering that moulded one life, and yet not it alone.

What You Did Not Tell is a personal memoir infused with unshakeable historical analysis, oozing with Dr Zhivago dare-do romanticism, with tangential flights into the mysterious and still undeciphered Voynich manuscript, Walter Benjamin’s moment of coup de foudre for his future wife while finishing his dissertation on Capri, or an 1882 British cricket victory over Australia, and the real-life original for Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey. It is as much a private memoir as it is a 20th-century history of the Left, its aspirations, ideological ventures, its controversies, delusions and dark monsters. It is a story of a Russian Jew’s journey, ultimately representative of the fate and calling of an entire nation. The academic fibre is dense, detailed, absorbing, a lesson in sleuthing and mystery, on the necessity of evidence and the critical value of leaps of faith, blind or well-gauged. Still darkness remains, and perhaps it is in this darkness, Mazower suggests, that our harshest and at the same time our most fragile secret truths exist.

Today we fight only for “the perfection of [our] own souls”, not for others around us, and it would seem Max Mazower and his generation, his sort of idiosyncrasy and human quality, far surpass our own moment in time. Mazower knows to be self-ironic, using shock with good (and at times terrible) measure to shake us into an awareness of our hallowed, benighted state, and all that it inadequately conceals. His point of emphasis is precisely on the moral effort necessary so that we may face the past but also so that we may relate to a fellow life. His grandfather – and others like him, if not in their mind’s turn, then certainly in their keenness not to watch life pass them by – denied us their own voice with regard to most of their secrets and suffering, leaving us with an unsettling sense of empty invincibility, of a chilling protective vacuum. It is a vacuum Mazower attacks judiciously, undauntedly, almost fondly.

There is, nonetheless, a strong, lingering whiff of nostalgia for a leftist myth and utopia, a mixture of affection, denial and sharp insight in this ode to Old North London, especially Hampstead, the Heath and Highgate. There is, too, a gingerly relationship with the fluctuations of Jewish sentiment and experience towards Russia – as the eternal homeland, the Tsarist regime of vicious prosecution but also opportunity, the Soviet labyrinth offering with one hand what it tore away savagely with the other. There is something goosebumpy about a Jewish boy, Mark Mazower’s father, growing up in London and calling the civilian war preparations “great fun”. What You Did Not Tell is the chronicle of an absence throbbing with presence; it is about disjunctions, compromises, deliberations and especially fragmented, all-too-human hope. It is a daring declaration of peace with resignation as a gesture of almost equal radicalism, a powerful, intimate approach to a momentous slice of history.

Mark Mazower’s previous books include Inside Hitler’s Greece, Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century, The Balkans, which won the Wolfson Prize for History, Salonika: City of Ghosts, which won both the Runciman Prize and the Duff Cooper Prize, and Governing the World: The History of an Idea. He has taught at the University of Sussex, Princeton University and Birkbeck College, University of London, and is now Professor of History at Columbia University. What You Did Not Tell is published in hardback and eBook by Allen Lane/Penguin.

Mark Mazower’s previous books include Inside Hitler’s Greece, Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century, The Balkans, which won the Wolfson Prize for History, Salonika: City of Ghosts, which won both the Runciman Prize and the Duff Cooper Prize, and Governing the World: The History of an Idea. He has taught at the University of Sussex, Princeton University and Birkbeck College, University of London, and is now Professor of History at Columbia University. What You Did Not Tell is published in hardback and eBook by Allen Lane/Penguin.

Read more

mazower.com

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.