The devil you know

by A.M. BakalarMirjana Novaković’s Fear and His Servant, set in 18th-century Serbia under Austrian rule, begins with the journey to Belgrade of the Devil in the guise of Count Otto von Habsburg, accompanied by his equally diabolical servant Novak. On the way to the city their carriage breaks down. In the thick fog at the crack of dawn the count encounters another traveller. Klaus Radetzky, special investigator in the service of His Imperial Majesty Karl VI, reluctantly discloses he is part of a special commission investigating occurrences “of a strange and horrifying nature” in which an Austrian tax-collector has been attacked and mauled by vampires.

The Devil is deeply concerned, verging on panic, over these unusual developments because the dead rising as vampires signals the dreaded Second Coming and Last Judgement. He wants to “stop the whole thing. Stop the twisted resurrection they heralded. Prevent the coming of the Antichrist and with it the coming of Christ himself.” The wheel in the carriage changed, von Habsburg and his servant proceed to Belgrade, where a costume ball, “the most important event of the autumn”, is to take place at the residence of the Regent of Serbia. In the city, von Habsburg conveniently assumes the role of special imperial investigator, which ensures cooperation from various parties.

Novaković spins an exquisite novel webbed in truth and lies; a joyful puzzle for the reader. Fear and His Servant brilliantly plays with the idea of what makes who we are, how much what we choose to reveal about ourselves really speaks the truth. Not even the Devil himself, it seems, is free of self-doubt. Above all, the image of self seems just a construct to play with, whether devised by our own doing or through the beholder’s perception. “The time I have spent among the rabble of mankind has taught me that people love and enjoy nothing so much as their belief that a lie is in fact the truth,” says the Devil. Vanity, and exaggerating self-importance through half-truths, are the perfect way to invent oneself, according to whatever image we hold in our minds. But don’t we all want to be seen in the best possible light?

At the ball the Regent Alexander of Württemberg comments, ‘Only the Devil would disguise himself as himself and still not find anyone to believe it.’”

Ahead of the costume ball, von Habsburg visits the workroom of Count Schmettau in search of a mask. All outfits have been already taken, including one of Christ – whom the Devil refers to as ‘Fishmouth’ – even Joan of Arc and a Greek philosopher. As a last resort, von Habsburg settles on a costume and mask of… a devil: “The costume was, of course, red. I spotted a pointy tail. The mask was also red, with a pair of stubby horns and some ghastly teeth. And really, I do cut such a handsome figure. But that’s the lying Christian creed for you.”

At the ball the Regent Alexander of Württemberg comments, “Only the Devil would disguise himself as himself and still not find anyone to believe it.” This lack of proper recognition and respect the Devil encounters is his constant disappointment in humankind. Earlier, Novak is less than pleased when the Devil offers him work:

He fired the answer back like the best Austrian cannon. “For you? Get thee behind me, Satan!”

“Yes, quite. Although, frankly, I don’t know how you expect to get ahead in today’s Europe with such an intolerant attitude.”

Novak mocks the Devil and wonders how he should introduce his master when they encounter bandits in the middle of the night, “As the Devil or as Otto von Habsburg?” The Devil is well aware, despite being the ruler of Hell, that he is not the most feared person and he will not pretend otherwise.

“Don’t be stupid! Even if I did announce myself as the Devil, who would believe me? They’d think I was out of my mind. It’s happened before, and you know perfectly well. I can’t stand it when you play the fool.”

The most telling encounter comes between the Devil and the Regent, whose actual title is Head of Administration.

“But how very galling it could be, the behaviour I had to put up with sometimes. And from human beings. Do people not read books, the New Testament? Does it not say quite clearly that I am Prince of this World?… Here was this petty bureaucrat instructing me – me, mind you, the ruler of this world and all it holds – on the finer points of addressing him. On one side, the lord of all the world; on the other, a head of administration.”

The one person who appreciates the Devil for his wit and intelligence is Maria Augusta, Princess of Thurn and Taxis, and the second narrator of the novel. Her story, which takes places years after the main storyline narrated by the Devil, offers an alternative truth. Maria Augusta considers the count an “exceptionally well-educated man”. She suffers from lack of love, since her husband hates her. Unbeknownst to Maria Augusta the Devil wants to seduce her. And yet, though Maria Augusta likes to think of herself as a good person, the Devil ridicules her avowedly charitable efforts because her true motivation “comes from the Holy Trinity: power, pleasure and pride. Oh, the world is mine, verily it is mine!”

There is something deliciously enjoyable in reading a portrayal of the Devil who experiences bouts of fear and panic, frets over his appearance and lack of respect, but at the same time enjoys the company of “souls with breath and badness”, and comes across as a rather well-read and tolerant intellectual.

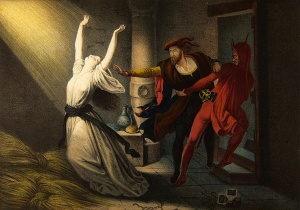

Faust and Mephisto in the dungeon. Lithograph by Joseph Fay, Paris, 1846. Frankfurter Goethe-Haus/Wikimedia Commons

Western culture has a long history of the Devil in literature. Mephistopheles in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus is a serious and demonic figure. Goethe’s version of the devil in his seminal Faust is a cynical nihilist and a sceptic, though he seems understanding about the human condition: “Man moves me to compassion,” he tells God. In The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov’s masterpiece set during the Stalin regime, Professor Woland arrives in Moscow with his diabolical entourage including the black cat Behemoth who speaks and has a taste for vodka. Woland is a truly flamboyant and charming character, but don’t be fooled because he can be cruel and afflict deep pain and trauma on his victims. Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz offers a lighthearted version of the devil in his playful ballad ‘Pani Twardowska’, in which Pan Twardowski promises Mephistopheles his soul if he can endure living with his wife for one year. The request proves too much for the poor Devil, who escapes through a keyhole.

Further afield, Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in his political satire of post-independence Devil on the Cross centres the narrative around the Devil’s Feast, a celebration of Kenyan criminals to elect the greatest of them all. Thiong’o’s Devil is the master of the ruling class set to exploit ordinary Kenyans. The capitalist forces employ the help of the Devil’s Angels, a group of bandits and thugs ready to use whatever violent means necessary, including death, to ensure the survival of the rulers under the Devil’s auspice.

Novaković’s Devil is very different to those forerunners; more benevolent and not so chilling, he does not flaunt his threatening powers. He is certainly not a character you will fear or feel uncomfortable with; his observations about human nature are noteworthy. It may be easy to lose yourself in the comic aspect of the novel but one of the pleasures of reading this narrative is peeling its many layers. Fear and His Servant has plenty to say about the failings of humans as proud, petty and self-obsessed beings, yet love and truth, as hinted when we first encounter the Devil in the opening chapter, are for him the pinnacle of human experience.

The Devil mercilessly mocks those who sell their soul to him. He is not interested in such an exchange; what he craves is an altruist, not a person who expects something in return. And this is where true love comes to the picture.

“All the men and women who serve me, every last one of them, fell into ruin long before meeting me. Besides, I’m not interested in buying. Like everyone else, I want gifts that come from the heart, the gift without a price… I have yet to meet a soul that will offer itself to me freely and not ask for anything in return.”

“It’s love you’re looking for, master,” his servant aptly observes, to which the Devil responds, “Don’t be daft… Love is easy to come by. I’m not looking for love.”

Later, the Devil bemoans that humans lost the ability to experience “pure, exalted love”. He blames books that distort the image of what true love is and instil unrealistic expectations in people.

“They shall burn with me, all those scribblers and their damned books, the ones to blame for people no longer loving each other, for everyone waiting to see what comes along next… changing their minds, and wanting something better, wanting only the best – and all without questioning whether they themselves are worth it.”

Novaković could easily be speaking about our own century, our obsession with a perfect and unrealistic image of how we should look, who we should love, who is the most desirable. But now it is not books but platforms like Instagram, Facebook, YouTube. In this respect Fear and His Servant is very contemporary novel, indirectly mocking our unhealthy infatuation with our own image as projected on social media or in glossy magazines.

In a world where everybody has a version of themselves in mind, and a different story to tell, it is the Devil who comes across as the honest one among the liars.”

Towards the end of the narrative, the Devil begins to reminisce on his encounters with the Son of God, accusing him of telling lies: “Fishmouth’s stories were nothing but hot air,” says the Devil, whereas what comes from his own mouth, even if he makes the telling a little more ‘interesting’ for listeners, essentially states “everything that happened and how it happened,” and thus he is the only one whose stories can be trusted.

And so the novel becomes “the tangled web of lies and truth”, depending which narrator the reader wishes to believe or whose story to follow. In a world where everybody has a version of themselves in mind, and a different story to tell, it is the Devil who comes across as the honest one among the liars.

“Throughout our lives we learn how to uncover false words, to turn them over and find the truth beneath them. When at last we come face to face with truth itself, we are helpless. Because falsehoods make sense, and truth does not.”

Fear and His Servant is effortlessly enjoyable, also thanks to Terence McEneny’s flawless translation. Novaković offers a number of interpretational layers across time and space. It is surprisingly contemporary despite being set in 18th-century Europe with flashes into the time of Christ and the future. A truly original vision of truth and myth.

Mirjana Novaković, born in 1966 in Belgrade, is the author of three critically acclaimed novels, each shortlisted for the NIN Award, the most prestigious literary award for Serbian authors, and a collection of short stories. Fear and His Servant, translated by Terence McEneny, is out now in paperback, as part of the Peter Owen World Series: Serbia, published in collaboration with Istros Books.

Mirjana Novaković, born in 1966 in Belgrade, is the author of three critically acclaimed novels, each shortlisted for the NIN Award, the most prestigious literary award for Serbian authors, and a collection of short stories. Fear and His Servant, translated by Terence McEneny, is out now in paperback, as part of the Peter Owen World Series: Serbia, published in collaboration with Istros Books.

Read more

Terence McEneny is from upstate New York and studied at the University of Nottingham. From 2005 to 2014 he taught conference interpreting at the University of Novi Sad, Serbia, before moving to Texas and becoming a staff interpreter in the federal court. His other literary translations include Destiny, Annotated by Radoslav Petković and a collection of Montenegrin short fiction.

A.M. Bakalar was born and raised in Wroclaw, Poland and lives in London. Her first novel Madame Mephisto was published in 2012 by Stork Press, and her writing has appeared in publications including the Guardian and The New York Times International Edition. Her second novel Children of Our Age is published by Jantar Publishing.

Read more

ambakalar.com