The accidental activist

by Mark Reynolds ‘‘To say that Rob Bilott is understated,’’ his colleague Edison Hill says, ‘‘is an understatement,’’ reported Nathaniel Rich in the New York Times Magazine article that inspired Mark Ruffalo to snap up the film rights to story of the mild-mannered corporate defence lawyer who went rogue and took on the might of DuPont. Shortly before he became a partner at Cincinatti law firm Taft Stettinius & Hollister in 1998, Bilott received a phone call from cattle farmer Wilbur Tennant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, who claimed his animals were being poisoned by drinking from a creek that was fouled by chemicals leaching from a nearby DuPont landfill site. Bilott’s grandmother had lived close by, and as a child he had spent a summer on a neighbouring farm, where family members recalled that Bilott had grown up to become an environmental lawyer, and put his name forward to the Tennants. Although his firm’s existence relied on defending corporate clients, and his work was all about protecting chemical companies from lawsuits, Bilott agreed to look into the Tennants’ case. ‘It just felt like the right thing to do,’’ he told Rich. ‘‘I felt a connection to those folks.’’

‘‘To say that Rob Bilott is understated,’’ his colleague Edison Hill says, ‘‘is an understatement,’’ reported Nathaniel Rich in the New York Times Magazine article that inspired Mark Ruffalo to snap up the film rights to story of the mild-mannered corporate defence lawyer who went rogue and took on the might of DuPont. Shortly before he became a partner at Cincinatti law firm Taft Stettinius & Hollister in 1998, Bilott received a phone call from cattle farmer Wilbur Tennant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, who claimed his animals were being poisoned by drinking from a creek that was fouled by chemicals leaching from a nearby DuPont landfill site. Bilott’s grandmother had lived close by, and as a child he had spent a summer on a neighbouring farm, where family members recalled that Bilott had grown up to become an environmental lawyer, and put his name forward to the Tennants. Although his firm’s existence relied on defending corporate clients, and his work was all about protecting chemical companies from lawsuits, Bilott agreed to look into the Tennants’ case. ‘It just felt like the right thing to do,’’ he told Rich. ‘‘I felt a connection to those folks.’’

Wilbur Tennant showed Bilott alarming video footage in which his previously docile animals had turned aggressive and deranged, with physical malformations ranging from humped backs, patchy hides and blackened teeth to organ failure. It turned out that a mysterious chemical named PFOA, short for perfluorooctanoic acid, had contaminated the water supply – not only on the farm, but in the surrounding neighbourhood. DuPont had been purchasing the chemical from 3M since 1951, its main use being in the production of Teflon and other non-stick, water- or heat-resistant coatings. In the subsequent decades, tons of the substance were pumped into the Ohio River and dumped into unlined pits on Dupont’s Parkersburg chemical plant, from where it entered the local water supply serving over 100,000 residents.

DuPont had for decades been actively trying to conceal their actions. They knew this stuff was harmful, and they put it in the water anyway. These were bad facts.’’

In the course of his investigations, Bilott uncovered secret studies by DuPont into the dangers of the chemical, whose structure is resistant to degradation, and if ingested by animals or humans binds to plasma proteins in the blood and circulates through every organ. As early as the 1970s, DuPont discovered high concentrations of PFOA in the blood of its factory workers, but failed to report their findings to the Environmental Protection Agency. Tellingly, the compound is not regulated by the EPA, since the agency was only empowered when it began operations in 1970 to investigate newly developed chemicals. Big Chem has thus been allowed to effectively self-regulate for decades without being compelled to disclose any troubling findings. The EPA can only investigate when it has been supplied with evidence of harm – which explains why at the time of Rich’s article the agency had only restricted five chemicals out of the tens of thousands on the market over four-and-a-half decades. In 1981, 3M found a link to birth defects in rats, and during the 1990s DuPont became aware of links to testicular, pancreatic and liver cancers in animals and humans. Then in 2000, when 3M ceased production of PFOA, DuPont – which was making $1 billion a year in profits from Teflon – invested in a new factory to make the compound for themselves.

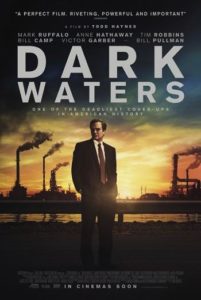

Tim Robbins as Tom Terp, Anne Hathaway as Sarah Barlage and Mark Ruffalo as Robert Bilott in Dark Waters

“DuPont had for decades been actively trying to conceal their actions,” says Bilott. “They knew this stuff was harmful, and they put it in the water anyway. These were bad facts.’’ Supported by his supervising partner in the firm Tom Terp, in 2001 Bilott filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the residents of the Ohio River Valley. Volunteers whose health was compromised by exposure to the chemical were offered $400 each to participate in blood tests, which in turn have resulted in over 3,500 personal-injury lawsuits against DuPont, only a handful of which have so far been settled. DuPont has set aside $671 million – or two-thirds of one year’s profits from Teflon – as a provision to settle all further claims.

Over thousands of working hours across over two decades, Bilott’s obsessive scramble for truth and justice has jeopardised his professional reputation and livelihood, his health and family happiness. As producer and star of Dark Waters, Ruffalo invests Bilott’s David-versus-Goliath story with unwavering conviction and absorbing sensitivity, and invites audiences to share his anger and to take action. “What we are talking about is the power of the individual to affect massive change, with the help of a community,” he says. “I think the ultimate message is that we need each other. No one else is going to do it for us. No one else is going to make the world a better place. It is us together. And this story about water transcends all political divides, ideological beliefs, sex, race, religion. We all know inherently how important it is for us to have clean water, and it is by framing these massive problems in these kinds of ways that I think we will see real positive change in the world.”

The film celebrates “the unlikely hero par excellence,” says director Todd Haynes. “Mistrustful, unpartisan and constitutionally guarded by nature, Rob Bilott, like most classic whistleblowers, is already a solitary figure when the story begins. And true to form, the events that unfold only further that isolation. That this isolation, this stigma, is mirrored in the story’s precipitating force, Wilbur Tennant (Bill Camp), and can be seen spreading across the network of interdependent players, crossing class differences, afflicting public life, family life, church life in its wake, describes its unique insidious contagion. Despite these bonds, taking on powerful interests will shrink your world and rattle your faculties.”

“I am a huge optimist, in that I believe in the power of the individual,” adds Tim Robbins, who plays Tom Terp. “One person can stop a mob. One rational voice can change public opinion. It doesn’t have to be a massive movement before it’s a righteous cause. Who is going to hold those in power responsible? I believe it’s the individual. It is the Robert Bilotts of this world that give me hope for the future.”

“Rob Bilott’s not in it for the glory,” concludes Anne Hathaway (Sarah Barlage Bilott). “He’s not in it for the instant gratification. This is a long, long path that he’s walked, and he’d be the first person to say that he hasn’t walked it alone. One of the things I think the film does so successfully is show that this remarkable person, within an environment that was flawed, was ultimately really supported. Together, they were able to do something. Now, that’s not just the end of the story. One of my favourite things about the movie is what happens next. What happens next is… us. We have to show up. We have to show up for our planet, each other and ourselves.”

Dark Waters is a Participant/Willi Hill/Killer Films production, distributed in UK cinemas by Entertainment One, and on US digital channels by Focus Features. The screenplay is written by Mario Correa and Matthew Michael Carnahan.

@entonegroup

@DarkWaters_UK

@FocusFeatures

@DarkWatersMovie

Robert Bilott’s Exposure is published by Simon & Schuster.

Robert Bilott’s Exposure is published by Simon & Schuster.

Read more

Take action

PFOA is just one compound in a family of over 4,000 chemicals known as PFAS, which are known as ‘forever chemicals’ because they don’t break down in the environment. Their use is so widespread over so many decades, it is estimated that 99 per cent of all living organisms now contain traces of the chemicals. In early 2019, the US Environment Protection Agency announced an Action Plan to address PFAS, but two decades after Rob Bilott wrote to them alerting them to the dangers, the chemicals are still unregulated in drinking water. DuPont agreed to phase out use of PFOA in 2015, replacing it with a new compound known as Gen-X, which itself is now showing up in waterways and has been seen to cause tumours in rats similar to those seen in animals exposed to PFAS.

The makers of Dark Waters are leading a campaign against forever chemicals in all their guises. More info:

darkwatersfilm.co.uk

darkwaters.participant.com

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista