We are all addicts

by Vesna Main– I feel sorry for Richard.

– You always do.

– Do you see him as an addict?

– Well–

– What would his therapist say?

– It all depends on how you look at it. First, it’s the person-not-called-Bob who mentions the idea when he presents Richard with the facts. We can sack you for using the work computer to contact those women, he says, but if we say that you’re an addict, that you’re ill, and you agree to be treated, the situation would be different. Richard is furious. He isn’t an addict and is not going to accept that. I’m trying to help, not-Bob says. This is the only way out I can think of. Of course, when the child pornography issue comes up–

– Child pornography? Is that new?

– I might have forgotten to mention it. Anyway, Richard argues and tries to resist all the pressure from the university until not-Bob is told by the VC that Richard accessed child porn sites.

– Did he? Are you sure you want to go there? He can’t be that stupid.

– You’re not saying poor Richard this time.

– I don’t like this.

– He only looks for a few seconds.

– But why have him do that? He isn’t a pervert.

– He moves from one porn site to another, accidentally clicks on–

– Accidentally?

– As soon as he realises, he’s horrified and moves on but the record remains. So, once that comes out, not-Bob has no means or wish to help him. Richard’s desperate to make sure that not-Bob believes him; not-Bob tells him that it doesn’t matter what he believes. The computer technicians have a record of him accessing the site and that’s that. Richard has no option but to resign.

In one of the sessions with Stuart, Richard admits that while he was seeing prostitutes, from time to time he wondered whether he was an addict… he regularly felt a compulsion to go back to the women.”

– Wouldn’t they prosecute him? Report it to the police.

– They were going to. However, as not-Bob tells him later, the record disappears. Either they are incompetent in the computer support department or Richard has a friend there. Somebody sympathetic. Perhaps even somebody with similar interests.

– Or, the university tries to keep quiet about it.

– Possible. Certainly, there’s no follow up.

– Phew.

– Exactly. Anyway, as for addiction, Anna’s the next person who comes up with the idea that Richard’s an addict. A few weeks after the revelation, she starts reading about men visiting prostitutes and convinces herself that Richard is ill. In fact, that’s her way, one of her ways, of coping. If he’s ill, she should stay with him, she reasons. It’s as if he had a failed kidney. That’s why she insists on his treatment, on therapy. When she explains that to Richard, he dismisses the idea. If there’s one thing I can’t stand, he says, it is all these bloody amateur psychologists. First not-Bob and now you. Anna isn’t prepared to budge, either therapy or they part, she insists. You remember that?

– She isn’t a woman to compromise.

– Would you expect her to in the circumstances?

– Possibly.

– Only a male reader would.

– I’m a male reader.

– Even a male reader should have sympathy for her position.

– I do but I think she’s too hard on him.

– Talking of addiction, in one of the sessions with Stuart, Richard admits that while he was seeing prostitutes, from time to time he wondered whether he was an addict. So it’s not only not-Bob and Anna who think of it. Richard tells Stuart he regularly felt a compulsion to go back to the women.

– Wasn’t that because each experience was unsatisfactory?

– One way of looking at it.

– You said that he had persuaded himself that he needed just one more opportunity for a fulfilling experience. Did that make him an addict?

– Well, as you say, he persuaded himself. But wouldn’t an intelligent man understand that he was deluding himself? Anyway, what would he consider a fulfilling experience?

– I don’t know. You’re the author.

– I don’t believe there can be such a thing with a prostitute.

– Why not? I bet lots of men enjoy it.

– How can you say that?

– What do you mean?

– What’s your evidence?

– They go back.

– Richard went back and claims he didn’t enjoy it.

– He must have enjoyed it a bit.

– So, he’s lying.

– Well, I imagine he enjoyed it up to a point.

– I think what he really craves is warmth, more than anything sexual. As time passes, he begins to worry and checks online articles on addiction. He learns that addicts show compulsive behaviour that impinges on other areas of their lives. He manages to persuade himself that he isn’t an addict: he has never missed an appointment, professional or social–

– You made him late for Anna’s party.

– True. He didn’t intend to; he got lost on the way home.

– I see.

He’s aware that most of his emotional energy goes into justifying himself and feeding his activity. Sometimes he tells himself that he could have stopped whenever he wanted but in his heart of hearts, he may not believe that.”

– As for addiction, the way he reasons is that he hasn’t sacrificed other areas of his life: the family hasn’t been deprived of anything and his research is going better than anyone else’s in the department. Besides, he’s proud that he treated the women with respect, always paid what they asked for; always put the money in an envelope. He believed that a real addict wouldn’t have done that.

– What? Put the money in an envelope.

– No, silly. He wouldn’t have been so considerate.

– Why not? I thought you said he was doing it for himself.

– Yes. What I’m trying to show is that Richard tries to reason with himself, tries to persuade himself that he isn’t an addict because he’s in control.

– Right.

– However, he’s aware that most of his emotional energy goes into justifying himself and feeding his activity. Sometimes he tells himself that he could have stopped whenever he wanted but in his heart of hearts, he may not believe that. And so he asks Stuart for his opinion.

– What does Stuart say?

– Stuart likes the theory of an American psychologist called Stanton Peele.

– Which says?

– That we’re all addicts.

– That’s handy.

– Peele believes that our convenience-oriented culture, with its sophisticated technology, our need to seek constant entertainment, escapism, our culture of high stress, our culture that leads us to deny our limitations, seek instant gratification, breeds addicts.

– I could have told you that.

– He says we’re all addicted to one thing or another. But some addictions are more obvious than others, some more acceptable than others.

– Exactly.

– He says that you can’t only treat the individual, you have to address society.

– Where does that leave Richard?

– To plod on with Stuart. Don’t worry; he’s having a good time. He likes Stuart and he feels he has someone to talk to, ask for advice; confide in.

– Anna’s addicted too.

– We all are. And you’re right: her obsession with prostitutes is a problem.

– She must be spending lots of time on the internet.

– Not only that.

– ?

– I’ve got to go out now. I’ll tell you later.

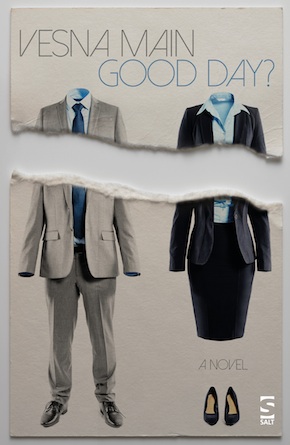

From Good Day? (Salt Publishing, £9.99)

Vesna Main was born in Zagreb, Croatia. She is a graduate in comparative literature and has a PhD from the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. She has worked as a journalist, lecturer and teacher, and her articles, reviews and short stories have appeared in newspapers and literary journals. She is the author of the novels A Woman With No Clothes On (Delancey Press, 2008) and The Reader the Writer (Mirador, 2015), the story collection Temptation: A User’s Guide (Salt, 2018) and the ‘fictional autobiography’ Only a Lodger… And Hardly That (Seagull Books, 2019). Good Day? is out now in paperback and eBook from Salt.

Vesna Main was born in Zagreb, Croatia. She is a graduate in comparative literature and has a PhD from the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. She has worked as a journalist, lecturer and teacher, and her articles, reviews and short stories have appeared in newspapers and literary journals. She is the author of the novels A Woman With No Clothes On (Delancey Press, 2008) and The Reader the Writer (Mirador, 2015), the story collection Temptation: A User’s Guide (Salt, 2018) and the ‘fictional autobiography’ Only a Lodger… And Hardly That (Seagull Books, 2019). Good Day? is out now in paperback and eBook from Salt.

Read more

vesnamain.wordpress.com

@VesnaMain

Author portrait © Chris Gilbert

Writers’ paths

Vesna Main: A novel in two voices