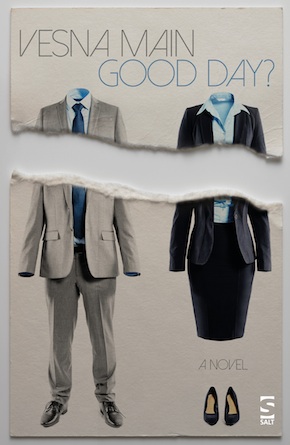

A novel in two voices

by Vesna Main

“Rarely can novelistic dialogue have managed to convey such complex nuances of meaning, motive and mood. A singular achievement.” Christopher Norris

In writing a story about what happens to a couple after the husband reveals that he has been visiting prostitutes for many years, I wanted to make readers aware of the trauma suffered by the partners of such men. The two main characters emerged quickly, mostly from interviews with women in that situation. Academic studies told me that men visiting prostitutes came from all walks of life. There was no racial conformity either. I was surprised to learn that not only were many men professional high-flyers and socially successful but also in happy long-term relationships. I made my protagonists, Richard and Anna, articulate, educated, middle-class people.

Initially, I wrote two versions of the story, both in the classic realist style, each with its own narrator, but always with a shifting point of view. The story had a conflict and, arguably, a resolution. However, I wasn’t happy with the result. As a writer who believes that the way a story is told is vital and has to be ‘of our time’, I was bothered by the idea of writing in a style that I associate with the positivism of the nineteenth century. I love modernism, and contemporary texts that pretend that it never happened do not resonate with me. At the same time, I feared that too much formal experimentation might obscure the political message of the story. I couldn’t sacrifice the issue about which I had strong feelings.

Eventually, after two abandoned versions, I hit upon the idea of a dialogue between a woman Writer and a Reader, her husband. Richard and Anna became characters in the novel she was writing. In this way, the text had two equally important points of view and the dialogue structure suited the questioning nature of the exchange between the Reader and the Writer which, as the story progresses, becomes increasingly confrontational, with the two regularly siding with a character according to their gender role.

What did freedom mean in relation to punters and sex workers? How free were the men whose passion became an addiction? How free were the women who had no choice but to sell their bodies?”

My strong feelings about the subject propelled me to write the text very quickly. I already had the story developed in the two conventional versions and it was only a matter of following the new form. The dialogue also allowed me to raise numerous questions that had been buzzing in my liberal feminist mind: Was the sex industry the same as any other? What did freedom mean in relation to punters and sex workers? How free were the men whose passion became an addiction? How free were the women who had no choice but to sell their bodies?

The form of a novel-within-a-novel brings out the idea that the Writer and the Reader are true denizens of a post-modernist world as their experience is always mediated through a text. That, however, doesn’t diminish their identification with Richard and Anna.

Finally, I think that despite its dark theme, revealing the pain and tension of a marriage, the novel is not without humour, in particular when it mocks its genesis, and blurs the division between the realities of the two pairs of characters.

Vesna Main was born in Zagreb, Croatia. She is a graduate in comparative literature and has a PhD from the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. She has worked as a journalist, lecturer and teacher, and her articles, reviews and short stories have appeared in newspapers and literary journals. She is the author of the novels A Woman With No Clothes On (Delancey Press, 2008) and The Reader the Writer (Mirador, 2015), the story collection Temptation: A User’s Guide (Salt, 2018) and the ‘fictional autobiography’ Only a Lodger… And Hardly That (Seagull Books, 2019). Good Day? is out now in paperback and eBook from Salt.

Read more

vesnamain.wordpress.com

@VesnaMain