The view from below

by Mark ReynoldsRobert Macfarlane’s Underland: A Deep Time Journey has its roots in three ‘surfacings’ that occurred in the spring and summer of 2010: the explosion of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull, the Deep Water Horizon blow-out in the Gulf of Mexico, and the entrapment of 33 miners at the San José copper and gold mine in northern Chile. These events, noted Macfarlane at a recent event at the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room moderated by writer and academic Alexandra Harris, “erupted the underworld into global consciousness; they did so with the power of story, with the power of logistical disruption, and with the power of a kind of industrial exposure of the networks of extraction, exploitation and alienated labour that underwrite pretty much everything that we do as a globalised extraction economy.”

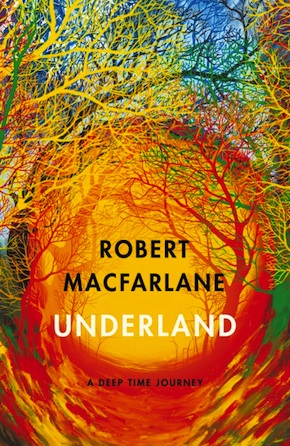

In this passionate, profound and poetic new book, drawing on more than six years of exploration, the author of The Wild Places, Landmarks and The Old Ways marks a shift in his ongoing mapping of landscape and the human heart, and ventures deep into the bedrock to examine our place in the universe and in time. Moving engagingly from the work of scientists detecting the pulse of the Big Bang to the ultimate inevitability of a post-human future, he shares his wonder for everything from prehistoric art in Norwegian sea-caves and the blue depths of the Greenland ice cap, to Britain’s Bronze Age funeral chambers, the catacombs of Paris, sinkholes in Slovenia and the intricate networks of roots and fungi – known as the ‘wood wide web’ – through which different species in a forest interact to share nutrients, enzymes and warnings of disease.

“Underland is where time goes back as far as the planet,” says Macfarlane, “and Deep Time is something that’s fascinated me since I began writing. I was writing about it in Mountains of the Mind, I first met it in the mountains. Mountains are so naked in their geology that they are temporally dizzying places to be.

“The great geological writers – Hutton, Lyle, Darwin actually, and Jacquetta Hawkes in the mid-century – knew that you have to anchor perception within the immensities of Deep Time, and I think that often comes down to detail; the scaling object in a piece of writing or a piece of thinking, that might be the toy, might be the ice seen as crystal, the tiny, delicate tree of ice that a glacier will grow overnight, as opposed to ice as this great cryospheric force that’s always busy mutating.

“We’ve been around. of course, for such a blink of a geological eye, so there are these inhuman – and more than human – expanses of rock and ice and weather and water that have moved in these intentful, or certainly massively agential ways for far longer than we’ve been here. So I wanted the reader to descend, to come under pressure, in darkness, and then to surface. I wanted the reader to go on their own journey into the underland, and into Deep Time, and so the book always was from the beginning going to be a descent and surfacing.

“In the chambers I abandon the first person altogether and try to find a way of gathering some of the stories of the underland that have come from myths, cultures, communities, voices around the world… I tell these stories absolutely in the present tense and just let them resonate, so they become echo chambers, effectively. That was just a way of letting time flow and obey different rules, which is what is does in the underworld, that’s one of the reason we value that realm.”

Often the lines are so pared down, verbs disintegrate and give way to lyrical description steeped in myth:

Up and over crag and boulder to a headland shoulder, each step sore now, the wind colder. Pack heavy, head heavy, throat chilled, body older.

Resurfacing after a descent – sometimes days later – brings fresh insights and revelations.

“There is a sense of escape,” he reflects, “and one of the things that going down makes new again is the surface… I’ve never been as amazed by the colour green as when I came up from 40 feet underground in the Mendips, and suddenly green was a liquid that soaked into my bones. And similarly on the glaciers, the blue of time, the blue of compressed ice, when as ice compresses it eliminates all the other wavelengths so you get that astonishing crevasse blue that glows. The only worldly colour rhyme that I know of is what’s called Cherenkov light, which is produced when radiation is underway in water, in a scatter of extreme energy moving through water. So colour becomes astonishing again, because the underworld is rarely colourful.”

All of which emphasises the darkness beneath – and within us. “Clearly there are parts of mind where we put hurt and grief and loss and kinds of love, and they disperse or they are hidden from daily view, and then there are the terrible things we do to each other as a species. We are an astonishing, miraculous, beautiful, hopeful, collaborative species, and we are a brutal, exploitative, murderous, solipsistic species. And there are chapters in the book which inevitably come face to face with that kind of darkness, where we put the worst we’ve made and the worst we’ve done.”

You enter a glacier’s aura. A big glacier, a big mass of ice, you feel the temperature drop as you approach it, because it has its own weather system. That’s astonishing, to be close to a creature like that.”

But the book is never less than a celebration of the natural world, and Macfarlane was particularly awed while camping beside Arctic glaciers, which he aptly describes as “noisy neighbours”.

“They really let rip with calving events, cries, grumbles… The sonic booms that big calving events release pass through your bones, you can feel it moving your lungs and your organs. Glaciers really, really do the bass beat astonishingly well. You enter a glacier’s aura. A big glacier, a big mass of ice, you feel the temperature drop as you approach it, because it has its own weather system. That’s astonishing, to be close to a creature like that.”

After relaying his intimate journey among such powerful forces of nature, it’s no surprise that an early question from the audience asks whether he is optimistic or cynical about our ability to deal with the looming climate crisis.

“I’m not sure I’d oppose optimism and cynicism,” he interjects,“[but] I despair at resignation, and I think what I see now, this month, this spring and summer, is a tighter clinch than I’ve ever seen between urgency and action. It’s been an absolutely fascinating, thrilling, devastating few months. The news has got worse and worse in terms of climate breakdown and ecological crisis. But I’ve also seen change accelerating and mutating in ways that were not thinkable last calendar year.”

He cites a referendum on the biodiversity crisis in Bavaria that counter-intuitively saw a conservative, farm-reliant German state vote in favour of massive structural upheaval in agriculture, the wave of Extinction Rebellion actions, school strikes and the efforts of youngsters like Greta Thunberg to mobilise change, and MPs, councils and parliaments now lining up to declare a climate emergency.

“I see the systemic limits, absolutely,” he concludes, “but I also see that we are beginning to align social justice and environmental justice in our political imaginaries in ways that are very, very powerful; that we are seeing that making a better, cleaner world is good for the vulnerable – human and more than human. And we are also seeing that this better world is a hopeful world, it’s not a regressive world. So I see hope in our visions, if not in our futures.”

Robert Macfarlane is a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and writes on environmentalism, literature and travel for publications including the Guardian, The Sunday Times and The New York Times. Among his previous books, Mountains of the Mind won the Guardian First Book Award and the Somerset Maugham Award and The Wild Places won the Boardman-Tasker Award. Both were adapted for television by the BBC. The Lost Words, co-created with Jackie Morris, won the 2018 Books Are My Bag Beautiful Book Award and the Hay Festival Book of the Year. Underland is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Hamish Hamilton and Penguin Digital.

Robert Macfarlane is a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and writes on environmentalism, literature and travel for publications including the Guardian, The Sunday Times and The New York Times. Among his previous books, Mountains of the Mind won the Guardian First Book Award and the Somerset Maugham Award and The Wild Places won the Boardman-Tasker Award. Both were adapted for television by the BBC. The Lost Words, co-created with Jackie Morris, won the 2018 Books Are My Bag Beautiful Book Award and the Hay Festival Book of the Year. Underland is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Hamish Hamilton and Penguin Digital.

Read more

@RobGMacfarlane

robgmacfarlane

Author portrait © Brian David Stevens

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista