Ahmed Fagih: After the revolution

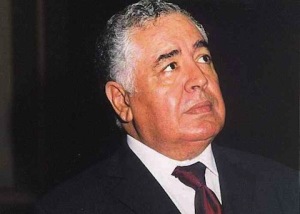

by Freddie ReynoldsIn 2008, Ethan Chorin’s Translating Libya, an anthology of short literary works by Libyan authors he had encountered whilst working as a US diplomat in Tripoli, shed light on hidden aspects of Libyan life and exposed the rich cultural heritage of a country that in Western eyes was solely dominated by vast, barren desert and a megalomaniac ruler. As Darf Publishers puts out a new edition reflecting on the effects of the 2011 revolution and the tectonic changes that the North African nation has experienced over recent years, I catch up with renowned author Ahmed Fagih, who wrote a foreword to the new edition, and whose story ‘The Locusts’ is included in the collection.

FR: You write in your foreword that Translating Libya “is like a time capsule”. What does it tell us about the country you grew up in?

AF: This book introduces Libya – its land, people and character. The stories are written by Libyan writers and depict different aspects of Libyan societies, whether urban or Bedouin or otherwise, in terms of place and subject. Writers who belong to different generations and different regions hope to enable the Western reader to have a better understanding of the country, in addition to what he can learn from the media and books of history, geography, politics, sociology.

It’s a wide-ranging collection…

I think it’s vital that the stories cover a wide spectrum of interests. Ethan Chorin introduces different styles and schools of thought as well as different colours and flavours. That way, the stories are successful in representing genuine and rounded pictures of the spirit of the country.

You’ve written such a variety of works. What attracted you to the short story?

To put things in perspective, I have written 22 novels and 22 books of short stories, 40 short and long plays, as well as 20 or so books of essays. I think I was able to tackle different forms of literature because there were no strong literary traditions and no well-established institutions, which could impose certain direction for the writer to follow.

The benefits of sticking to writing one genre, accumulating experiences, taking chances and experimenting with it, are perhaps much better and more beneficial for the writer than being constantly on the move, crossing borders from one genre to another. But that is how I responded to the lure of the freedom that existed for me. I can write the way I like – venture across the frontiers and jump over different genres as I please. There is no demand for me to write in a certain genre, or any call from the publishing establishment asking me to respond to what’s required by the market, for the very obvious reason that no publishing establishment existed in the country until very recent times. A very limited and insignificant market for the book – a huge vacuum – leaves the writer with complete freedom to write or not to write. That is the sort of environment I came from.

The writer in our part of the world doesn’t depend on writing for his livelihood. Naguib Mahfouz remained a government employee until the day of his retirement.”

The pressure on Tennessee Williams to write his plays came from Broadway. The entertainment industry needs him as a playwright, not as a novelist, a poet or essayist. The publishing industry needs Hemingway as a novelist to satisfy the large readership that awaits his narrative books. That goes for others needed by Hollywood, or by TV, the cartoon industry, or children’s books.

The writer in our part of the world has neither Broadway nor Hollywood and doesn’t even depend on writing for his livelihood. It’s not strange that the late Naguib Mahfouz remained a government employee in Egypt until the day of his retirement. Forty masterpiece novels were in the market, yet he was still living on his monthly salary. In America a writer of the same generation, J.D. Salinger, was able to live on the revenue of a novel that sustained him for sixty years.

Libya, with its roots in the desert and Bedouin society, is more conducive to the short narrative than the long, which needs a modernised, civilised and urban environment. When I started writing and publishing short stories in the sixties, there were no writers making any serious attempt to write novels. There was a complete lack of a publishing industry, and the novel can usually only be published in book form, while the short story can find its way to the reader in the pages of journal or a magazine. When I published my first book of stories, The Sea Has No Water, in 1966 it was only the tenth or eleventh literary book published in Libya since the invention of the printing press. There was a physical impossibility of writing and publishing any form of literature on the lengthy side.

At the same time the newly founded state of Libya encouraged journalism and the publication of different kinds of magazines and newspapers that needed to be filled with literary articles, poems and short stories.

How do you think the influence of a foreign editor affected the collection?

Ethan Chorin came to Libya with a lot of curiosity. It was an unknown quantity to many Americans. His intention was to distinguish truth from fiction and, through a very inventive approach, he used fiction as a means by which to discover that truth. Fortunately for him, the revolution erupted while he was still in service and it revealed to him the brutal regime that was ruling the country. He learnt so many facts that the military regime was trying to hide and the sufferings the Libyan people had had to go through. Although he originally finished writing this book and published it before the revolution, he had a good chance to review what he wrote and to prepare the new edition, complementing his earlier work.

I think he was sincere and honest and had real sympathy for the country, its people and its writers, and really provided them with a platform to address a different audience from the one they intended to address when they first wrote their stories. It shows in the book that he has affection for the literary material he included and has a good eye for picking what is successful in representing the soul of the country.

Tell us about your story ‘The Locusts’.

I was a newcomer to Tripoli from my remote desert village Mizda when I started writing stories. I had very little experience outside my life in that village, so I turned to the past and to my young life for inspiration and material to feed my creative writings. I was driven by a feeling of devotion to the village, and with some sense of being indebted to it. In fact, most of the stories I wrote at the beginning of my career were driven by the passion I felt for my village and its people. I appreciated their hardships and sufferings and the struggle for livelihood they had to endure in that hostile environment.

The locusts in the story invaded the village to destroy whatever little greenness the villagers used for grazing their goats. It was a force of nature, coming to inflict harm, so it was only fair that I make the people of the village mobilise themselves, get up early and collect the locusts while they were still sleeping and bring them home and grill them to feed their children. I was one of those children who were fed on those locusts. It was a kind of war, and perhaps a very justifiable one.

‘The Locusts’ was one of the earliest stories I wrote, published in the early sixties in a daily newspaper and included in my first book of short fiction. It was republished continually in literary journals, as if it struck a chord somewhere in the Arab consciousness or touched upon some sensitive nerve.

There must be some negative aspects to being brought up among an illiterate community, but the positive side of it was the freedom I enjoyed with my education, my cultural formation.”

I think every writer draws upon his experiences, looks to his environment and the people and places he knows best for inspiration. But I should hasten to add that we are individuals, different in our approaches and characteristics. As the Arab saying puts it, “Every Sheikh has his path”, so every writer may have his own method and programme of going about getting his inspirations and looking for his material and doing his writings.

What in particular influenced you?

Firstly, being born in a small primitive village in the desert in the early forties, an era of war. I was born in a family of illiteracy, no one in the family had had an education apart from a grandfather who was a teacher of the Qur’an who died before I was born. There must be some negative aspects to being brought up among an illiterate community, but the positive side of it was the freedom I enjoyed with my education, liberated from the influence of any member of the family imposing thoughts and ideas on my mind. It’s common in educated families to transfer their prejudices and loyalties and preferences to their children. My family had no way to affect my reading or place any pressure or supervision on my cultural formation. My formal education ended when I was 17 and I immediately started working as a civil servant. Whatever education I got afterwards was accompanied by work. I think that was a blessing in disguise because it meant liberty again.

My village, Mizda, was located at a crossroads where caravans from east and west, north and south, passed through. It was a melting pot of different popular cultures, rich with folkloric and traditional arts and crafts and folk tales. The complete lack of official culture in terms of libraries, cinemas, theatres, bands, music halls, books, journals, magazines and records was substituted by forms of culture that were manifested in the way they sing, dance, play music, perform wedding celebrations, welcome in the spring season, or express their happiness with the harvest when the barley fields are ready to be cut. I was able as a child to absorb such a multitude of cultures and forms of arts and literature, complementing them with the modern cultures that reached the village later on. I only left the countryside when I was fourteen years old, so those were vital years in forming the basis of my personality.

How has your work as a journalist informed your fiction?

Since there was no way or tradition of getting revenue from writing literature and, for someone like me, not enough education to take me to the world of academia to teach or to work, I was left with the option of working in journalism. Although such a profession can have a negative influence on people with literary inclinations, I was able to put it to better use. I insisted on working as a writer and not as a reporter or a news collector. I chose to write opinion columns and have been writing them since I was seventeen years of age, taking care that my style of writing be always literary and not the easy-going style of journals. I gained the best value of being a journalist and a writer, which can be done. García Márquez is the best example.

I learnt that writing is a job that has to be done. Journalism doesn’t recognise your need for inspiration, or being in the right mood. There is a deadline that has to be met and no way to surpass it. Journalism gave me a platform for my literary writings, because almost every piece of literature I wrote, including novels, were published first in newspapers and journals, exposed to the large audiences of a newspaper and not restricted to the small readership of the Arabic book market. Journalism was also able to put me in touch with the public. As a columnist I was engaged almost daily with issues and causes of interest to the general public, which gave an immediacy and urgency to my stories, novels and plays.

How did you use history to explore modern Libya?

The literary critic and Marxist thinker György Lukács linked the emergence of the historical novel with the struggle against absolutism. We all know there are eternal causes and issues that are not to be affected by the passing of time, which a writer of a novel, historical or otherwise, can turn to and address with no fear of being out of touch with his readers. We all still relate to works of literature that were written thousands of years ago: the Greek tragedies and comedies written by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes, Euripides, Apuleius.

As creative writers, we go to the past to highlight some aspects of our present lives. It’s not strange to see how Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall has echoed worries and concerns of modern politics in Britain.

Novels and stories and dramas are some sort of history, able to encompass present realities and past events, concerned with recording the history of our emotions and feelings and the inner lives of human beings. That’s not the concern of history books, or the job of historians, but authors.

In my book Maps of the Soul, I embodied the colonial leader of Libya in the thirties in the present-day ruler, and showed through that person the atrocities committed and the injustice inflicted upon the people of Libya. The paradox was that I found through painting the portrait of Field Marshal Italo Balbo that this fascist colonial leader was far more humane and reasonable than the murderous Colonel Gaddafi. Yet the novel was highly praised by Gaddafi himself!

In my book Maps of the Soul, I embodied the colonial leader of Libya in the thirties in the present-day ruler, and showed through that person the atrocities committed and the injustice inflicted upon the people of Libya. The paradox was that I found through painting the portrait of Field Marshal Italo Balbo that this fascist colonial leader was far more humane and reasonable than the murderous Colonel Gaddafi. Yet the novel was highly praised by Gaddafi himself!

How were you affected by the Gaddafi regime’s state censorship?

Regarding my novels, short stories and dramas, I never had any problem with censorship. In literature we speak from behind masks, and the mask means freedom. The problem was the black cloud that was hanging over our heads, writers or non-writers.

It’s different in the press or the media. As a journalist and columnist I experienced a lot of hardship to get my word through. A writer has to be tactful, resourceful, and has to avoid putting himself in danger.

There was a relative literary renaissance in February 2011, as the revolution gained momentum.

I really and truly felt, from the first day of the 17 February Revolution that a heavy burden was lifted off my chest, the nightmare was over. It only needed a moment of courage like this where the fear barrier is lifted, because the dictator maintained his power by the fear he sowed in the hearts of the Libyan people. Such a savage, inhumane and barbaric regime has no basis to rule for such a long period of time. It had already outlived its days, and should have disappeared forty years ago.

I felt like a long-distance swimmer who was restricted to swim in a little pond and suddenly saw that the ocean is open for him.”

So I enjoyed an inner freedom I had never experienced before and joined the force of the revolution from the first moment. I was writing and publishing articles every day to enhance the chances of success of the revolution and going through a moment of euphoria, writing almost feverishly to express the anger I felt as the regime used firing squads, killing people marching in the streets in peaceful demonstrations. The Gaddafi regime was sending threats, both personal and through the media, to kill me, but I went on in my support of the revolution.

Now the country is liberated from the chains of dictatorship, and that should be reflected in the soul of every creative writer and artist. We all regret the aftermath of the revolution, yet there was a sense of relief at the ousting of the rule of terror, combined with a sense of achievement at being able to defeat it. As a writer, I felt like a long-distance swimmer who was restricted to swim in a little pond and suddenly saw that the ocean is open for him.

As for Libyan literature as whole, and how it is affected by these developments, it is perhaps too early to judge. But the new era should open new avenues for writers, and will definitely result in a prosperous literary movement in the near future.

The author Ghazi Gheblawi told me that: “the dictatorship rotted the fabric of society. People are not proud to be Libyan.” What role can authors play in rebuilding Libya?

What my friend Ghazi says is very true. I have great faith in the healing powers of the arts and literature, if they are put to good use. Libya needs a strategy for rebuilding its state and society and its human resources, and if it fails to do so the country can only continue to be a wasteland of broken human souls, as it was under Gaddafi`s rule.

The problem is not with authors and artists, and how they can help. They were always there, ready to contribute to enhance the enrichment of the lives of the people of their country, and inject power and vitality in the quality of the country’s artistic and literary scene. The problem is whether the new ruling elite is able to realise the potential and power of arts and literature in repairing the damage done to the soul of the country and recognise their contribution in the rehabilitation process, so Libya can liberate itself from the negative effect of four decades of evil rule.

The works translated and published by Darf are an indication of the right way we should work to introduce ourselves to the world. But Darf is an individual voice, it has neither the resources of a government nor of the state of Libya, and it is not supposed to do their job.

As they say, one bird cannot make a spring. And the spring of Libyan literature in the international arena can only be achieved through a scheme organised by the government of Libya. If there is a chance to have a government in Libya that has the wisdom and the understanding to do so, it will change the perception of Libya in the world to a better one.

What are you hopes for Libya?

At the moment Libya is going through a period of chaos inflicted on the people of the country by trigger-happy militia men. The rule of law is absent, but it’s a transitional period – it will pass away, it will disappear, and Libya will come back to itself again. Peace will prevail and the rule of law will be installed, and central government, elected by the people, will take over from the rule of the militias. I am sure of it because what is happening now was imposed by illegal means, and illegal weapons, and it can’t go on for long. People won’t allow it to go on. In this age of globalisation the chaos and terrorism stemmed from the present situation in Libya will spill over. Indeed it is causing damage to neighbouring countries and the harm is reaching the north banks of the Mediterranean. There are enough signs and indications that a central Libyan government is to be agreed upon and a unified stand is to be taken from different political entities. Libya has huge material resources but because Gaddafi wished to invest only in what can satisfy his own needs, the rest was considered kind of surplus. That would be part of the scheme to realise future aspirations.

What’s next for you?

Writing is like breathing for me, so I am now writing my 23rd novel, one that explores a subject matter I never dealt with in the past. It explores life onboard a huge oil tanker, the interactions and dealings between its captain and crew and challenges of navigating in high seas and through cruel and brutal storms.

Ahmed Fagih was born in 1942 in the village of Mizda, 100 miles south of Tripoli. He worked as a journalist in Tripoli until 1962, when he won a scholarship to study theatre at London’s New Era Academy of Drama and Music. In 1972 he returned to Libya to head the National Institute of Music and Drama, in the same year becoming editor of the influential Al-Usbu’ Ath-Thaqafi (Cultural Weekly). Fagih’s major work, a trilogy with the English titles I Shall Present You With Another City, These Are the Borders of My Kingdom and A Tunnel Lit by a Woman, won the prize for best novel at the 1991 Beirut Book Fair. Collections of Fagih’s short stories include: Fasten Your Seat Belts (1968), The Stars Disappeared (1976), A Woman of Light (1985) and Mirrors of Venice (1997). Several of his novels have been translated into English, including Maps of the Soul (Darf, 2014) and Homeless Rats (Quartet, 2011). Fagih has had a long, parallel diplomatic career, having previously headed Libya’s missions in Greece and Romania. In the wake of the 2011 Revolution, he defected to the rebel government and continued as Libya’s Ambassador to the Arab League, based in Cairo.

Ahmed Fagih was born in 1942 in the village of Mizda, 100 miles south of Tripoli. He worked as a journalist in Tripoli until 1962, when he won a scholarship to study theatre at London’s New Era Academy of Drama and Music. In 1972 he returned to Libya to head the National Institute of Music and Drama, in the same year becoming editor of the influential Al-Usbu’ Ath-Thaqafi (Cultural Weekly). Fagih’s major work, a trilogy with the English titles I Shall Present You With Another City, These Are the Borders of My Kingdom and A Tunnel Lit by a Woman, won the prize for best novel at the 1991 Beirut Book Fair. Collections of Fagih’s short stories include: Fasten Your Seat Belts (1968), The Stars Disappeared (1976), A Woman of Light (1985) and Mirrors of Venice (1997). Several of his novels have been translated into English, including Maps of the Soul (Darf, 2014) and Homeless Rats (Quartet, 2011). Fagih has had a long, parallel diplomatic career, having previously headed Libya’s missions in Greece and Romania. In the wake of the 2011 Revolution, he defected to the rebel government and continued as Libya’s Ambassador to the Arab League, based in Cairo.

Translating Libya: In Search of the Libyan Short Story, edited by Ethan Chorin and with a foreword by Ahmed Fagih, is published by Darf Publishers in paperback, priced £8.99. Read more.

Freddie Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer whose work has appeared in print and online for publications including HUCK, Little White Lies, Compass Cultura, Flux and Traveller.

freddiereynolds.com