All, nothing and everything in between

by Mika Provata-CarloneAs people travelled across Europe in the late 16th century, fleeing the Spanish Inquisition, a word travelled with them – nada; a nothingness of prospects, a future where nothing remained and everything was lost, a universe where the centre of faith was being fiercely usurped by the massive, ponderous vacuum of doubt and agnosticism, of religious nihilism and atheism. Mojca Kumerdej’s The Harvest of Chronos takes place during that troubled period of peasant revolts, religious persecution and ethnic submission or determination, of violence and the dawn of a different consciousness, set in a small corner of Mitteleuropa that is now Slovenia, a country as much touched by myth as by the harshest strokes of reality.

Her story is given a specific historical frame – the ruthlessly spasmodic efforts by the rulers of the hereditary lands of Inner Austria to control popular dissidence, the dissemination of dangerous ideas, religious liberalism, especially the nascent concept of independent nations. Using the persona of a Prince-Bishop who inspects the state of this Catholic turf of Christendom, Kumerdej produces a highly concentrated, almost impenetrably dense chronicle of the staged witch-hunts and mock trials that, after claiming about 1,000 lives, assured a return to obedience, guaranteed the prolongation of the realm and perhaps foreshadowed the future of much of later Europe.

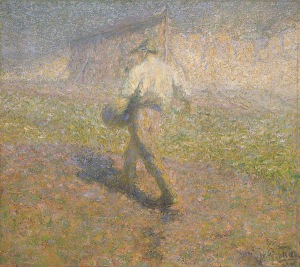

The Harvest of Chronos takes its cue from an iconic modernist Slovene painting, The Sower, a critical metaphor and image to encapsulate the nation’s history, fate and destiny. Slovenia, from that particular prism of ethnographic projectionism, is a land of farmers of time, of men confronting history and the whimsy of the wheel of fortune in order to reap – in order to harvest, in Kumerdej’s own foundation narrative of that modernity – their place in history. Pride in an autochthonous culture, however poor or rustic, in the resistance against overlords who are presented in the direst shades of putrid grey or nauseous green, and in the transcendental madness and power of vision of men of letters rather than of those yielding arms, these are the key points of reference for Kumerdej’s grand project of defining the identity of a nation by means of one of its historical moments of martyrdom.

Kumerdej employs with great detail and generous erudition a style of religious pastoral realism to evoke the tribalism and rawness of that moment in time between darkness and light.”

That this is an ambitious project would be an understatement. The Harvest of Chronos spans 379 intricately embroidered, compactly written pages, and aims to tackle themes such as God and the Devil, good and evil, women and men, witches and craved freedom, memory and misery, forgetting, and a life that can pass for mankind as it does for animals and inanimate alike. It seeks an eschatological, theological agenda in order to challenge ideas about God and creation, to question or celebrate a creation without God, to review the anthropomorphic tradition in religious practice. It aspires to expose the connections between the cycles of history and the cyclicity of the natural world, to deliberate on the supremacy of divine will, of human free will and on the inevitability of emptiness and doom. It conjures lavishly, even if too tightly and microscopically, the tensions between faith and the medieval mind. Kumerdej employs with great detail and generous erudition a style of religious pastoral realism to evoke the tribalism and rawness of that moment in time between darkness and light.

Hers is serious scholarship that results in a carefully constructed, painstakingly embellished narrative fabric, a historical novel in the most traditional sense of the word, where Brueghel meets Tom Jones, meets The Name of The Rose. The Harvest of Chronos is richly opulent, almost gossipy in period detail and vernacular atmosphere, with a tremendous emphasis on human voices, on the inner or outer workings of language and thought. The story looms alarming and chilling, engrossing in its promise, although it often feels somewhat over-involved and laboured. The effort to erect a rich tapestry of the times here is achieved at the expense of the wisdom of selection, of narrative economy and of a stricter evaluation of authorial aims and focus. Kumerdej’s dialogues, monologues or streams of consciousness, in their almost improbable sophistication, can render the flow stodgy on occasion – recitatives that halt rather than promote development and transition, lending an aura of opera buffa to what is clearly intended as high melodrama.

As in her previous works, Kumerdej evinces her ability for relentless analysis of layers and shadows, of engaging with vice and desire, of casting violence, blind ambition, gender politics or national polemics in protagonistic roles. Here, with a gregarious sprinkling of historical curiosities (chocolate included), ethnographic detail, almost authentic tones and echoes from contemporary chronicles, folk and religious lore, medicine and nascent science, she presents us with what is fundamentally a stationary picaresque tale, full of holy visions and human horrors, an ineffable web of superstition and sexual desire, arcane mysticism and ambition. At the heart of the darkness lies the conflict between heresy and religious cleansing, between Catholicism and a popularised version of Lutheranism, between a vision of life that includes sanctity (and even saintliness) and a secular determination to celebrate the material world. Anti-Semitism and a tacit background of the pogroms cohabit the pages with off-the-cuff reflections on Platonism and Aristotle, with popular beliefs on golems and the new marvellous automata, with the marvels and yearned for licentiousness of Venice or the New World, or with almost obsessive portrayals of witches and clergymen, and their sinister secret lives full of obliging “little Angels”. It is, at times, a rather robust, top-heavy mix of shock and spice.

As popular fiction, it stands its ground with a certain panache and novelty… it is also a human story with substantial resonance, from a literary tradition which has not yet found its place among English audiences sufficiently widely.”

Kumerdej clearly relishes her storytelling, and takes pride in adding trimmings, ornaments or scholarly insignia to her text, in choosing angles, or in displaying vast tableaux and panoramas. She is however encumbered by an anachronistic tendency to psychoanalyse, to project, at times overwhelmingly, modern soul-searching or the understanding of identity, agency, inwardness, onto a period setting that cannot sustain that weight or its levity.

The Harvest of Chronos is satisfying in its meatiness as far as rich detail is concerned, or its slow, penny-dreadful feel. As popular fiction, it stands its ground with a certain panache and novelty. In all fairness, it is also a human story with very substantial resonance, a narrative from a literary tradition which has not yet found its place among English audiences sufficiently widely. It is equally an attempt to perceive causes and effects, motives and subterfuges for a historical phenomenon dense with evil and perversion, with the drunkenness for power, where murder was conceived as a transcendentalising act – for times and events that make the tales of the Grimm brothers pale into blunt insignificance. With a clearer sense of authorial limits and broader aims, unshackled by what emerges as a disconcerting self-reflexivity, like a ventriloquist looking almost ecstatically at her puppets as they ‘speak’ their lives within the story, this would have been a volume of considerable interest. The translator’s introduction makes promises the novel itself sadly fails to keep – more discipline would be required for the proclaimed place of The Harvest of Chronos in Slovene literary tradition, and less staging would have provided a better mise en abyme for the human drama, for the ethics and philosophical peregrinations, the national history Kumerdej has in mind. The Harvest of Chronos is perhaps a lush popular yarn; it would have taken both more and less to make it into a literary achievement.

Mojca Kumerdej is a Slovenian writer, philosopher, critic and cultural correspondent for the daily newspaper Delo. Her stories have been translated into many languages and have been published in various literary journals and anthologies. In 2017 she received a Prešeren Fund Award for h.er second novel Kronosova žetev, now published by Istros Books as The Harvest of Chronos, translated by Rawley Grau.

Mojca Kumerdej is a Slovenian writer, philosopher, critic and cultural correspondent for the daily newspaper Delo. Her stories have been translated into many languages and have been published in various literary journals and anthologies. In 2017 she received a Prešeren Fund Award for h.er second novel Kronosova žetev, now published by Istros Books as The Harvest of Chronos, translated by Rawley Grau.

Read more

Author portrait © Jože Suhadolnik

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.