Alternative Palestines

by Basma Ghalayini

PALESTINIANS HAVE THIS JOKE (it’s not very funny): A Gazan is running frantically down the street. Someone grabs him and asks: ‘What’s going on? Has something happened?’ ‘No,’ the man replies, ‘but it might.’

Through 77 years of occupation, violence, displacement, and repeated collective punishment, Palestinians have never stopped running. Not just from the soldiers on their streets, the drones and F35s in their skies, the warships in their seas, the informants in their midst, or the world’s most technologically-advanced, politically-impervious military state bearing down on all sides, but from an idea, a century-old myth, a fantasy: that you can spread a map out on a table somewhere and simply invent a country, regardless of what already exists there. It’s a European fantasy, of course. This particular one being the brainchild of Theodor Herzl, an atheist Jewish journalist from Budapest, who sought to heal ‘the wound’ of antisemitism in Europe by creating a completely new Jewish homeland.

Through a lifetime of lobbying and organising, Herzl put various proposals for such a state – including Lord Chamberlain’s later-abandoned ‘Uganda Scheme’ – onto the European political agenda, that is to say, onto politicians’ tables. Herzl wasn’t the only European to indulge in table-top fantasies, of course. In late 1915, when British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot sat down at tables in London and Paris and secretly drew straight lines through lands that didn’t belong to them, and through lives that they would never know, dividing the spoils of the Ottoman empire between three other empires, they too were indulging in a fantasy: one that would soon (if briefly) cohere with Herzl’s. The new British colony of Mandatory Palestine would need partners on the ground, proxies to eventually take on the dirty work; and two years after the Sykes-Picot agreement was ratified, the British found their proxy, their co-fantasists, in the Zionists. When Lord Balfour scribbled his famous 1917 ‘declaration’ – a document with no legal or moral basis – green-lighting the creation of a new country for a community that at that time only made up five per cent of the population on the ground, it was yet another exercise in fantasy world-building.

The infamous Plan Dalet had no arbitrary divisions, no unnatural straight lines. It simply wanted everything – all of Palestine. This was a fantasy dripping with blood.”

Five years later, in 1922, this fantasy acquired a veneer of legitimacy when the newly-formed League of Nations voted to include Balfour’s terms as part of the British Mandate. There then followed waves of Jewish immigrants arriving in Palestine, resulting in a series of uprisings and strikes among Palestinians, which culminated in the so-called Arab Revolt (1936-39), a three-year-long rebellion demanding independence from the British and an end to the Zionist plan. During the Revolt, the British government’s Peel Commission visited Palestine and concluded that a partition between the newcomers and the indigenous people was in order. Ultimately, the Arab Revolt was unsuccessful and was suppressed by the British Military with the support of emerging Zionist paramilitary gangs, like the Hagana and Irgun. In response to the Revolt, the British government issued a White Paper in 1939 allowing for the establishment of a Jewish ‘national home’ in an independent Palestinian state, but limiting further Jewish immigration and restricting the Jewish incomers’ ability to buy land, overriding the Peel Commission which had called for a simple partition.

But different peoples’ fantasies can only coexist for so long. In 1946, in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the Hagana, Lehi and Irgun Zionist militias turned on the British, launching several attacks against them, including the bombing of King David Hotel where the British were headquartered, killing 91. The following year, Zionist delegations to the newly-formed United Nations and intense lobbying of Truman’s White House led to the ‘Partition Plan’, aka Resolution 181, being adopted by the UN in New York in November 1947. Perhaps the table this plan was drawn up on was slightly wider than the one Sykes and Picot had used, but the thinking was just as detached. Resolution 181 called for the end of the British Mandate and the division of the country into two halves, giving much of the Mediterranean coast, the North East and the Southern tip to the Jews, and establishing Jerusalem as an extraterritorial, international zone. As a result, clashes erupted between Palestinians and the incomers, continuing until the British disengaged from Palestine altogether in 1948. Despite the Zionists having lobbied the UN and US intensely, the year before, for the Partition Plan’s map, by March 1948 the Zionists in Palestine had adopted a whole new plan that went far beyond 181’s proposed borders: the infamous Plan Dalet. Wherever this plan was drawn up, on whatever table, it had no arbitrary divisions, no unnatural straight lines. It simply wanted everything – all of Palestine. This was a fantasy dripping with blood.

Headed by David Ben Gurion, Plan Dalet’s tactics included laying siege to Palestinian villages, bombing Palestinian neighbourhoods, forcibly expelling inhabitants, setting fields and houses on fire, and detonating TNT in the rubble of already-destroyed buildings to prevent people from returning. Using detailed inventories of Palestinian villages’ families, assets, power structures and allegiances, that the Zionists had meticulously gathered over many years, the militias – led by the Hagenah and including the Irgun and Stern (or Lehi) gangs – launched a campaign of terror that ultimately displaced 750,000 Palestinians from their homes, secured 80 per cent of historic Palestine for the Jewish incomers, emptied eleven cities, ransacked 531 villages, committed over 70 massacres, and killed at least 15,000 Palestinians. Israelis may refer to this war by other names; to Palestinians, it has only ever been called one thing: the ‘Nakba’, the catastrophe.

But Palestinians haven’t just been running their whole lives from violent, Western fantasies. They’ve also been running from their own trauma – private, collective and intergenerational trauma. And the route you take to escape trauma isn’t always clear. Trauma doesn’t follow any rules. It is fundamentally dreamlike in its nature: indeed the word ‘dream’ and ‘trauma’ stem from the same root (the ancient Greek root word: τραῦμα, meaning ‘wound’).

The two years of genocide we’ve all just witnessed constitute yet another dreamlike trauma that Palestinians will always be running from. A living nightmare, live-streamed on social media, making us see things that we can never unsee. As with all dreams, it has collapsed our sense of space (for us in the diaspora, bringing ‘back home’ closer to us than where we now live) as well as collapsing our sense of time. The past has telescoped into the present. Horror stories our grandparents once told us, from 77 years ago, have played out once more in our reels. The Nakba then has become the Nakba now.

This was the thinking behind Palestine Minus One: for twelve Palestinian writers to process the magnitude of what has been happening, offering an alternative, more distant iteration of the old Nakba, in place of the new.”

Just one example: on the wall of a flat in Manchester, a new key hangs – a modern, Yale latch key: the key to my mum’s apartment in Shalihat in Gaza which, after being bombed and repurposed as a watchtower by IDF snipers, was then reduced to rubble. The key on the wall echoes the classic symbol of Palestinian identity: the old, bulky, rusty keys that all Palestinian families kept as heirlooms, passing them down from one generation to the next: keys to our grandparents’ homes, that they hoped their descendants would one day return to.

Sometimes we have to stop running. It’s unsustainable. When fantasy and trauma are the cause and effect of the Zionist project, one way to turn and face it might be to engage with the two Nakbas – the current and the original – by fighting these living nightmares with created ones: fighting one fantasy with others, fighting dreams with more dreams.

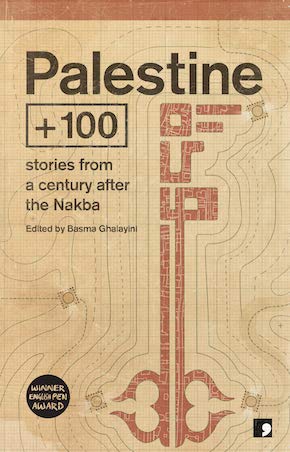

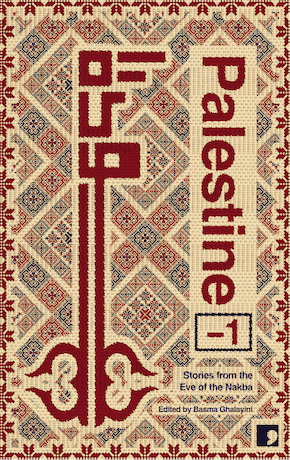

This was the thinking behind Palestine Minus One: not just a prequel to Palestine + 100 (which projected the pre-genocide trauma of Palestinians onto possible futures), but also an outlet for twelve Palestinian writers to try to process the magnitude of what has been happening, offering them an alternative, more distant iteration of the same thing: the old Nakba, in place of the new.

In the stories, a recurring theme is that this nightmare is itself recurring. In Anwar Hamed’s story, ‘Trapped’, a character inspired by Hind Rajab – the five-year-old girl targeted and shot by the IDF in her family’s car, along with six members of her family and the two paramedics coming to her aid – becomes a time traveller, portalling into other women’s lives, and metamorphosing into them at other, pivotal moments in Palestinian suffering.

While some characters fuse, others split and divide. In Sonia Sulaiman’s ‘The Dragon’, the narrator finds his identity cleaving into two, just at the moment he decides to flee, leaving a version of himself, and the life he was meant to have, forever behind. In Mazen Maarouf’s ‘A Chronicle of Grandad’s Last Days Asleep’, the narrator reflects, ‘It’s like there are two of me: one here and another over there’, before being rendered a ghost, who along with other ghost children, starts a new life as a house servant to the foreigners who’ve moved into his home. In Liana Badr’s ‘I Swear, This All Happened’, schoolgirls discuss the myth of the Qareena – a djinni-like twin or shadow that follows your every move in the underworld, guiding or misguiding you. Even buildings and institutions have a dark doppelganger that eventually replaces them: a Palestinian agricultural college, for instance, gets repurposed by the invaders as a mental institution.

Other strange recurrences echo through the book, internally and metatextually. Reading Badr’s descriptions of her beloved Dar al-Tifel al-Arabi school, founded by the formidable Hind al-Husseini, I was reminded of a group of children I’d known in my teens in Gaza, the ‘Abna’a al Sumud’ (children of resilience) – orphans of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres in Lebanon, brought to Gaza in the early 90s, and taken under Yasser Arafat’s wing personally.

Some of the most haunting ghosts in these stories are the settings – villages and neighbourhoods wiped from the map, their names contorted and disfigured or replaced completely. We can pay tribute to these original places (and their people), or we can be haunted by them. It’s up to us, all of us. It is no coincidence that the annihilation of these towns and villages provided the origin stories for countless political movements: George Habash, the founder of the Marxist PFLP, came from Al-Lydd (‘Lod’), the setting of Ibtisam Azem’s haunting story; two of the founders of Fateh – Salah Khalaf and Khalil El Wazir – were born in Yaffa and Ramle, respectively; Ahmed Yassine, the founder of Hamas, was born in Asqalan (‘Ashkelon’); all these places were obliterated by the Nakba, stolen, repurposed. If we don’t honour their original form, if we don’t remember their names, or the names of the massacres – Balad al-Sheikh, Sa’sa’, Deir Yassin, Tantara, al-Lydd, Saliha – they have no choice but to haunt us.

The speculative fiction devices used by the writers aren’t limited to horror. Abdalmuti Maqboul’s ‘Eastwards’ uses the superhero genre – that quintessentially American canon – to critique America’s role in the multiple Nakbas. Thus, ‘Vetoman’ (a nod to America’s decades-old protection of Israel at the UN) becomes an active participant in the al-Dawayima massacre, reminding us of America’s role in the development of this plan. The Biltmore Program, a stepping stone towards Plan Dalet, that openly proposed violence as the way forward for Zionism, was devised on a table somewhere in the Biltmore Hotel, New York, in 1942. And, to remind us that Israel’s formation had very little to do with the Holocaust, except in retroactive justification, Selma Dabbagh’s story, ‘Katamon’, echoes the assassination of Count Folke Bernadotte, a man who had been a hero to the Scandinavian Jewish community, having saved 450 Danish Jews from the Theresienstadt concentration camp, and who was, on being appointed the UN mediator for the Palestine-Israeli conflict, promptly assassinated by the Zionist Lehi militia.

These stories are all fictions, of course. But they raise a question that could and should be asked: if a new country is conjured out of thin air and made flesh through massacres and atrocities, should we be surprised by the violence it’s prepared to engage in to sustain itself? Should we be surprised by the ferocity of the 2014 onslaught on Gaza, for instance, or the 2012 bombardment, or the 2008-9 bombardment, or the violence inflicted during the two intifadas, or the everyday brutality of settlers and occupying forces in the West Bank, or the massacres of Sabra and Shatila, or the violence of 1967, and so on, and so on? Perhaps, if we knew anything about 1948, we wouldn’t be surprised at all. Perhaps we would be wary of the country’s geopolitical intentions. Perhaps we could even help it face the monster of its past.

There is a story from the early days of the Zionist movement: that Herzl or his colleagues sent two rabbis to Palestine, in the late 19th century, to investigate the viability of building a Jewish state there. They reported back with the message: ‘The bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man.’ Even in the early days, Zionists knew that Palestine was indeed a beautiful land, but that it belonged to others. As for these stories, they should leave you in no doubt: the bride is beautiful, and she has been, and always will be, married to another man.

From the introduction to Palestine Minus One

—

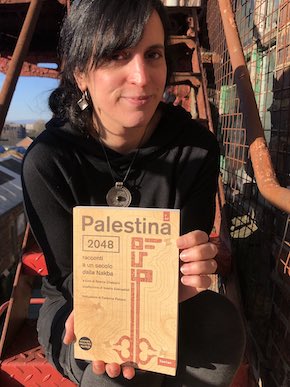

Basma Ghalayini (born 1983) is the Productions Manager at Comma Press and an occasional translator from the Arabic. She was born in Khan Younis and grew up in the Gaza Strip. She is the editor of Palestine + 100: Stories from a Century After the Nakba and Palestine Minus One: Stories from the Eve of the Nakba, both published by Comma Press (paperback, £11.99).

Read more

commapress.co.uk/basma-ghalayini

@commapress.bsky.social

instagram.com/commapress/