Amanda Lindhout: Compassion over hate

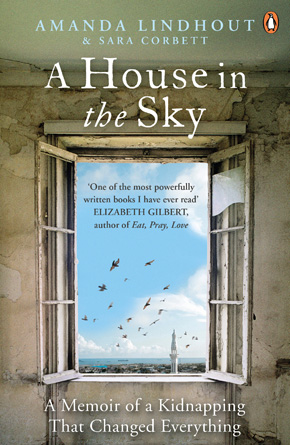

by Mark ReynoldsAmanda Lindhout’s remarkable memoir A House in the Sky tells the harrowing, ultimately inspirational story of her 460 days in captivity as a hostage in Somalia. Moved between derelict desert houses where she was kept in the dark, in chains, starved, and repeatedly beaten and abused by her teenage captors, she was able to call upon extraordinary depths of resolve, hope, fortitude and forgiveness as she dared to imagine life on the other side. The dramatic kidnapping and torturous, numbing days of captivity are prefaced by Lindhout’s childhood dreams of escape and subsequent travels around the world in her early twenties, first as a backpacker then as a rookie reporter chasing her big break.

Early in the book comes a quote from Paul Theroux – All news out of Africa is bad. It made me want to go there – which sums up the joyful exploration and youthful impetuousness of her earliest travels, whilst also giving a sense of foreboding for what’s to follow. It’s clear there’s a competitiveness to the backpacker scene that makes people look for increasingly extreme adventures.

“From my own experience, you’re pushing limits with every border that you cross,” she asserts. “I travelled so much in my twenties. I had been to over fifty countries by the time I went into Somalia. And as you cross borders you gain confidence in your ability to navigate the world. You’re in one country and the next one is just right there. And people who are out in the world and travelling like I was are by nature very curious, and that curiosity along with the confidence you build as you become an experienced traveller can lead you into countries that are quite off the beaten track and maybe not appealing to the average tourist who goes on a holiday once a year. You know, travelling was my life and I was starting to feel very confident about my ability to navigate anywhere in the world.”

When she was wavering about entering Afghanistan for the first time she was inspired to seize the moment while reading Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now. I ask what other lessons she has gleaned from that book, and about the moment she decided: yes I’m going.

“Well, that was the first time I had read his book. I was reading it on an overnight bus in India trying to get myself into Ladakh, and really immersed myself in it, regretting at the same time that I hadn’t gone into Afghanistan. Suddenly it was very, very clear to me with every part of my being that the next step for me to take was to go to Afghanistan, so I got off of the bus and bought a ticket all the way back and into Afghanistan. I know Eckhart Tolle quite well now, we’ve done public presentations together about forgiveness, and he’s somebody I’ve learned a lot from over the last couple of years and that I’ve called on many times when I’ve been facing challenging periods in my recovery.”

When she hit upon the idea of going to Somalia with Australian photographer and former boyfriend Nigel Brennan, she was looking essentially at three ‘good news’ stories, that the pair planned go in and report on in a week. Weighing up all potential risks and obstacles, she hired a trusted local fixer.

“I hired an expert on the ground,” she explains, “who told Nigel and I we needed three security guards, so we hired three security guards. Looking back, I could have done a lot of things differently, but with the information I was given I think we made relatively appropriate choices in terms of the security we hired. But we were going into a country that is one of the most lawless in the entire world, and of course I knew kidnapping was a risk. But by then I’d also been living in Baghdad as a reporter for eight months and you become acclimatised somehow to living in a war-torn environment, to being in such an intense place. It was supposed to be one week. We were going to go in, our primary story was out of this internally displaced people’s camp, and then Nigel and I thought we’d have a holiday on one of Kenya’s white sand beaches. That was our plan…”

Soon after the kidnapping Lindhout and Brennan realised the value of being seen to convert to Islam – as a survival tactic and to get inside the heads of their captors.

“I knew because I’d spent so much time in the Middle East that if I made the request to convert to Islam they would probably feel obligated to allow me to. It was important for me to understand how my captors saw the world, and what motivated them, so it was really fascinating to read their religious text over and over again. One of the young men, our abductor, led Nigel and I through the conversion and taught us the Islamic prayers. And we both started memorising the Koran as you do from the back to the front, at least the phonetics of it. So it was not only allowing us to have deeper insight into our captors’ minds and belief system, but it also gave us something to do, which in a situation like that is also very important – having some mental stimulation. Long-term it was a tactic that served me in many different ways, especially later when everything had gotten so dark and dirty. I’m not a religious person but I’m quite spiritual – and actually the practice of prayer is something I’ve carried over with me even outside of captivity. I don’t get down on my knees and pray five times a day, but I do really see the value in just taking time and moments every single day to say a prayer of gratitude for my freedom.”

As the first weeks dragged by, Lindhout observes: “There was nothing good about our days. We both knew it, but for me, being hopeful felt necessary, like pounding a fist on the wall in case somebody might hear it.” Brennan found it more difficult to find a way to optimism.

“I think Nigel would say that those first months were very difficult for him to adjust to, losing his freedom, as of course it was for me too. But sometimes when you have to be strong for another person you conjure up this strength. And because Nigel was having such a hard time I really needed to find that inside myself. After he and I were separated it was more difficult sometimes to feel hopeful. But at a certain point you have a choice – you either give up, and giving up in a situation like I was in could also mean death; or you grab onto hope, and resiliency, and at a certain point, at a dark point in captivity, that’s just what I needed to do for my own survival.”

She had a vision during captivity that she and Brennan had established an unshakeable connection, that when they got out they would “sit on each other’s porches for years to come”. It didn’t turn out that way.

“No it didn’t. It’s been a couple of years since Nigel and I have talked. Of course I sent him a copy of my book. In the acknowledgements I thank him and his family. And I have read his book, I don’t know if he’s read mine. We did try after we were released to maintain a relationship but what had happened to us changed both of us in really fundamental ways and I think our perspective on what happened was very different from one another. And, too, for those last ten months in captivity we weren’t together so we had very different experiences. We will always be in some way bonded by the experience of being abducted together but it’s not necessarily something that binds us together for the rest of our lives.”

In a situation that’s as severe as I was in you just have to go very deep inside of yourself to see what you’re made of and to look for any pockets of courage, of strength that are there and grab onto them.”

It was during the darkest months in isolation that Lindhout escaped internally to the ‘house in the sky’ of the title, where she was able to will herself to understand that it’s only her body that is suffering.

“I think in a situation that’s as severe as I was in you just have to go very deep inside of yourself to see what you’re made of and to look for any pockets of courage, of strength that are there and grab onto them. And what I was discovering in captivity was that my mind was remarkably strong and powerful and it had the ability to lift me out of my suffering. So I called the book A House in the Sky because that was for me this place I could go to, that was in my own mind, where I could live on memories of the beauty of the world and all the things I had experienced, and on imagination, thinking about the life that I could go on to live if I were to make it out of there.”

The most striking episode in the book is Lindhout’s out-of-body realisation as she’s being assaulted by her most persistent abuser that her captors had witnessed great horrors themselves. In that moment she understands for the first time she’s capable of feeling compassion towards them.

“Yeah, which was surprising to me. But I think compassion starts with an understanding, and what happened to me that day was an understanding about the people who were hurting me. They were mostly teenagers who were the victims of war and violence and then also they’re perpetuators of it. It is a sad state of affairs in a country like Somalia that there are these 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds, 18-year-olds, that haven’t been to school, that are shaped by war and violence and crime. And as that understanding grew inside of me so to did this tiny little seed of compassion. That’s what happened that day and it’s something I continued to build on through my time in captivity. Anytime I felt really overcome by anger and depression, I would try to go to that place of understanding and to remember who these young people were. And it helped me.”

Forgiveness is a choice that I make. In captivity it’s a choice that I made, it’s a choice I make now every day. But making the choice doesn’t mean you get there.”

She does note in the epilogue, however, that forgiveness is another step beyond compassion, and that it’s a place she can’t always get to.

“Yes, very true. Forgiveness is a choice that I make. In captivity it’s a choice that I made, it’s a choice I make now every day. But making the choice doesn’t mean you get there. I want to forgive to be free of all of that negative emotion. And some days when I experience that feeling of forgiveness, that does really feel like freedom to me. A lot of days I don’t get there, but I choose forgiveness every day because I want it so badly. And I think if I keep choosing it, it does become easier as time goes on to get to that place of understanding, compassion and forgiveness. It’s important to me.”

Another haunting image from the book is when she and Brennan try an escape. As they are cornered by their captors in a nearby mosque, a woman in her fifties clings onto Lindhout and tries desperately to prevent her from being recaptured. Soon after her release, Lindhout established a charitable organisation called the Global Enrichment Foundation, some work of which was set up specifically to honour the memory of this unknown woman, who was surrounded by gunmen as Lindhout was dragged from the mosque, and whose fate she has since been unable to determine despite repeated efforts to track her down.

“I’ve tried, I’ve tried. The New York Times magazine did a cover story on my book and sent a photographer into Somalia to photograph the mosque that I escaped to. While they were doing that I had their fixer – the same fixer I had used – ask around looking for the woman and we weren’t able to get any information about her. That woman is still very much with me every day. Our flagship initiative – we have many programmes now, but the first one that we launched with – was a university scholarship programme for Somali women inside Somalia. Today we have 46 women in university and their full university career is funded by the foundation, and it’s to honour that woman at the mosque.”

Lindhout and Brennan were eventually sprung from captivity and moved to Nairobi for recuperation and debriefing after their families and well-wishers raised part of the demanded ransom and a London-based ‘risk mitigation company’ cut a deal with the kidnappers. Publishers gathered soon after their release.

“It happened immediately. I wasn’t even back in Canada yet, I was in hospital in Kenya. It was overwhelming and I wasn’t sure that writing a book was something that I wanted to do, to be honest. It was such an immensely personal story that I’d lived through that I didn’t know if I wanted to share it with other people. But the turning point was when I met my co-author, Sara Corbett, through a mutual friend, Robert Draper [one of the two National Geographic reporters staying in the same hotel as Lindhout and Brennan in Mogadishu, who may have been the kidnappers’ original targets]. And when I met Sara and we sat down, we talked about what this story was to me. It was always a bigger story than just 460 days in captivity. It was the story of a young woman who came from a troubled childhood, who very much wanted to be out in the world, and what that looked like, and what motivated me. I also wanted to focus not too heavily on the abuse and everything I endured in captivity, though that needed to be there, but to focus instead on the moments of transcendence. And so, once she and I were really on the same page in terms of what this story actually was, then I felt confident about moving forward with it.”

Even with that shared vision, the book took three-and-a-half years of to-ing and fro-ing.

“For a couple of reasons – because of course it’s not an easy story to tell. Though the beginning of the book, which reads more like a travelogue, was really fun to work on, but then moving into the darker stuff… you know, I needed to be able to step away from the material sometimes. And also both Sara and I are total perfectionists and we would pass a piece of writing between us sometimes dozens of times until we felt we had it just right. It was important to me that the sensory details, the sounds and the smells and colours, were conveyed on the page too, and that required a lot from me to access memories, and later, as the story gets harder, accessing those memories was of course more difficult too.”

Next up are decisions to be made about a possible movie adaptation.

“I think it’ll happen,” Lindhout says, “it’s just again a matter of having the right team of people involved, making sure that I retain some creative control over the process too. It’s such a personal story, so I’d need to be a consultant on the film. But there are a lot of conversations taking place right now, so I think it’s something that will be seen in a couple of years, and I hope it will happen.”

Amanda delivers food aid in Somalia for the Global Enrichment Foundation’s Convoy for Hope programme

The first time Lindhout returned to Somalia after the release was to deliver food aid during the 2011 famine, and she went back four more times in quick succession – this time with kidnap-and-ransom insurance.

“Going back requires a lot of courage,” she admits, “because in some ways it’s like facing your biggest fear. The first time I went back, though, particularly, I was so moved and affected by what was happening with the famine. I’m somebody who has lived through hunger myself in a very severe way, so I was motivated to help and I was in a really good position to do something, and I’m really proud of that decision because that year we gave out over two million meals in response to the famine. So it’s hard, it’s hard going back, but the foundation is four years old now and it’s got legs of its own and it doesn’t require me to continuously go back into Somalia. Those were risks I was willing to assume for the work of the foundation, but there aren’t any plans to go back right now. I just don’t need to.”

So what is the programme from the foundation that has made her proudest?

“That’s a good question. The programme that reached the most people was our Convoy for Hope programme, the famine-relief programme, but I’m really proud of the Somali Women’s Scholarship programme, and the fact that I was really able to make good on that promise to myself to do something to honour the woman at the mosque. So the fact that is successfully off the ground is really great, and so too is the work we do now with Dr Hawa Abdi. The day I was kidnapped I was on my way to her camp, hoping in some way to inspire people to help her, and now I’m in a position to really do something to help her, and so we fund most of the infrastructure inside her camp, and that’s also work that I’m really, really proud of. She’s an incredible Somali activist who was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize two years ago, and a real hero of mine.”

Soon after her visits to the country one of the kidnappers got in touch on Facebook to congratulate her work with the foundation – which was uncomfortable to process.

“Getting it was really upsetting, of course, so I sent it on to the authorities and everything, but what I like about that is it sort of feels like a kind of justice to me. It’s very unlikely they’re ever going to be arrested and put into jail in a country like Somalia, so for me the fact that they know at least about the choices I’ve made afterwards, that I’ve chosen compassion over hate, that’s really important to me, and that really feels good to me, that they can see that despite everything I went through, I’ve gone on to live a life and to even give back to that country. I love that they see that.”

Journalistic assignments are definitively in the past as she looks forward to starting a course in psychology in September. But there could well be another collaboration with Sara Corbett down the line.

“Of course the collaboration with Sara was so important. I don’t know that I’d want to work on a book project without her, and it’s something we’ve talked about. I think there is more to say about the story, there is the whole other chapter of recovery, of building the foundation, of facing my fears and going back into Somalia, and so there may be another book in my future, but that would be a couple of years down the road.”

Amanda Lindhout is an award-winning humanitarian, social activist, public speaker and writer, as well as the Founder and former Executive Director of the Global Enrichment Foundation. A House in the Sky is published in the UK by Penguin in paperback and eBook.

amandalindhout.com

globalenrichmentfoundation.org

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.