How it begins

by Thea Lim

“A beautiful debut exploring how time, love, and sacrifice are never what they seem to be.” Kirkus Reviews

Donna likes to remind Polly that she has to earn her keep, by entertaining Donna. “You’re such a drag,” Donna says. “Go do something daring so I can live vicariously.”

Polly prefers to stay home and drink home-brew wine and watch TV with Donna’s two massive cats, Chicken and Noodles. “What happened today?” Donna yells as a way of greeting, when Polly comes home. “Gossip! If you don’t give me some gossip, you’re getting kicked to the curb!”

“We did some training on the new in-house phone system. Everyone got new extensions. You’re gonna love hearing about this.”

Later, Polly makes the mistake of telling Donna about Frank. “There’s a dishy bartender who works around the corner.”

“And…?”

There isn’t really anything else to say. She edits the story. “Today I sneezed and he gave me a napkin.”

“He. Likes. You. Quick, go back now. Where’s your coat?”

“You’re not serious. I’m in my Ziggy pyjamas.”

It is also only the second commercial break during the Laverne & Shirley season premiere, which they’ve been awaiting for weeks.

“You should go. You’ve been wanting to meet someone.” “I could go tomorrow.”

“Maybe tomorrow he’ll meet the love of his life. And you’ll have missed your chance. As soon as the credits go, take my car.” “If it’s meant to be, it’s meant to be, whether I go out there or not.”

“You have the worst attitude. No one has ever had a worse attitude than you.”

He waves to her and produces a screwdriver and places it on the bar. And then he winks. There’s a cherry in the drink, which must be a night thing.”

At ten p.m. the bar is a backwards, smoky facsimile of its daytime self, even if it is a Wednesday night. The tables are littered with the gunk of drink, and the stools are crammed with bodies, searching for a bewitching stranger to hold between their knees. Frank is leaning against the bar with his face resting on his hand, talking to a woman in green everything. Polly opens the door to exit, but this makes the bell overhead tinkle, and Frank sees her.

He waves to her and produces a screwdriver and places it on the bar. And then he winks. There’s a cherry in the drink, which must be a night thing. She had a book on her, but Donna confiscated it so that she wouldn’t look like a schoolmarm. She has nothing to do with her eyes. Around her, the bar screams with mirth.

Polly likes to think of herself in a certain way – self-assured, nonchalant. But the glare of this night-time world exposes her shyness, her inexperience. Her high-school friends are already engaged to their high-school boyfriends. Polly stares miserably at the cherry.

He is just her size, the height she’d be if she were a man. He has strong shoulders and a sweet face, a sinking combination.

Polly thinks, Stay or go, but quit feeling sorry for yourself. Her goal is to make herself immune to her surroundings, so she does not see how Frank looks around, pretending to scan the room but lighting too long on Polly, how Frank looks into the mirror over the bar, in order to see her face. This is how it begins, and she misses it. And so, when he places a matchbook in front of her, she looks at it confused, almost angry it seems, judging from her expression in that mirror over the bar. She puts the matches in her pocket and her money on the counter and she leaves. A few days later, she puts her hand in her jacket pocket, where she has forgotten the matchbook, maybe intentionally, and she is stupefied when she opens it and sees Frank’s name and number scribbled across the flap.

***

Frank suggests they go for a walk in Delaware Park. It is an endearing, old-fashioned suggestion, and Polly has to tell herself not to get her hopes up. When she arrives, he goes to hug her, and she is taken aback. Their bodies mismatch, one of his arms jammed awkwardly around her neck, while a six-pack of beer in a black plastic bag swings in his other hand, perilously near her ear. Why did he bring beer?

“Heh,” he says. “Almost clocked you in the head.” They step through the archway and her stomach gives a nasty twist. Sometime after, when it is too late to mention, she thinks about how he said “clocked” – a funny word she can’t remember ever hearing him say again. She remembers too his hand was so busy with his shirt, which rode up his pale belly when he hugged her, and she realizes he must have been nervous. She hadn’t known him well enough to read the signs.

Their bodies mismatch, one of his arms jammed awkwardly around her neck, while a six-pack of beer in a black plastic bag swings in his other hand, perilously near her ear. Why did he bring beer?”

The beer and the crude noise it makes when he opens it has her reconsidering the whole date. It is not at all that she is against drinking; she is just against drinking inelegantly, in the park. But they walk and get to talking, and when they return to where they began, they take the loop again. He tells her he is an out-of-work historian. He’s working at the bar to help a family friend and he’s going to get his high-school teaching credentials this fall. She admits that what she really wants to do is learn upholstery, as unexpected as it sounds, and she even tells him why. She has never told anyone before, but Frank asks. She wants to learn so that she can fix her mother’s love seat, mouldering inside the discount locker where it’s lingered for years.

They talk and talk, and she asks him how old he is, and it takes him a second to remember: he’s twenty-five. “The more years I have,” he says, “the less I remember them, and isn’t that terrible?” She thinks it’s such a nice thing to say.

When it begins to rain, first they huddle under her puny umbrella, and then eventually, he puts his arm around her, and the contact makes her voice crack. Gusts of rain heap up marshy piles of leaves, and the cars going by kick them down in streams of taillight red.

Frank asks if she wants to come to his place, to get out of the storm. It is across the street and around the corner. “It’s just up ahead,” he says, after they have walked five blocks. “Just around this corner,” he says, after another ten minutes. By the time he says, “It’s just the next street over,” the rain has stopped. The dark sky has cleared and it’s daytime again. “Do you still want to come in?” Frank asks, which makes Polly consider that the rain wasn’t just a cover to get her into his house, which means that now that the rain has stopped, he doesn’t want her to come in anymore, which means that she should decline.

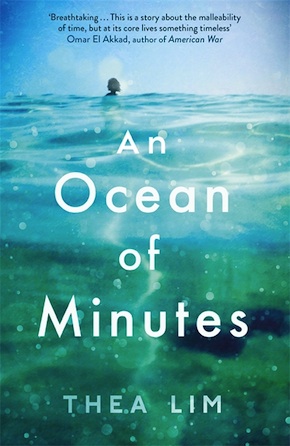

From An Ocean of Minutes (Quercus, £14.99)

Author portrait © Elisha Lim

Thea Lim‘s writing has been published by the Southampton Review, the Guardian, Salon, the Millions, Bitch Magazine, Utne Reader and others, and she has received multiple awards and fellowships for her work, including artists’ grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. She holds an MFA from the University of Houston and she previously served as nonfiction editor at Gulf Coast. She grew up in Singapore and lives in Toronto, where she is a professor of creative writing.

An Ocean of Minutes is published by Quercus in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

thealim.org

@thea_lim